Featured Faculty

Professor of Marketing; Mondelez Chair in Marketing; Marketing Department Chair

Polk Bros. Chair in Retailing; Professor of Marketing

Yevgenia Nayberg

As consumers, we want to believe there is a clear link between the wholesale price of a product and the price we end up paying for it. Research seems to support this belief: a number of theories predict that when there is a change in the wholesale price of a product—whether it is an orange or a flat-screen TV—the regular retail price will shift in proportion to that change.

“In the theoretical models there’s always a proportional response of some kind,” says Blakeley McShane, an associate professor of marketing at the Kellogg School.

But new research diverges from what shoppers assume and theory has long suggested. Using highly detailed, real-world data, McShane—along with Eric Anderson, a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School, Chaoqun Chen, a Kellogg graduate student in marketing, and Duncan Simester, at MIT’s Sloan School—found that regular retail prices (the shelf prices excluding any sales or promotions) do not always adjust proportionally to wholesale price changes.

In fact, about half the time the retail price does not change at all. Perhaps not surprisingly, it turns out that wholesale price increases are much more likely to be passed on to consumers than decreases.

“What retail managers do when faced with wholesale price changes is an important managerial decision,” McShane says. The decision is critical for retailers because it impacts their profits and profit margins; it is also critical for wholesalers, who ultimately depend on retailers to set a price that consumers will find acceptable.

To investigate these pricing decisions, the researchers worked with a very large national retail chain that sells products across a vast number of categories. They amassed data from the retailer on every time the wholesale price of a product changed over nearly four years, from January 2006 to September 2009—a total of 11,852 instances. Each time, they noted the direction and size of the wholesale price change, as well as any associated shift in the regular retail price.

One finding jumped out immediately: a full 44 percent of the time that a wholesale price changed, there was no change at all to the product’s retail price. This suggested to the researchers that managers take a two-pronged approach to pricing decisions: first, they decide whether (and in what direction) they will respond to a wholesale price change—and only later do they decide the magnitude of that change.

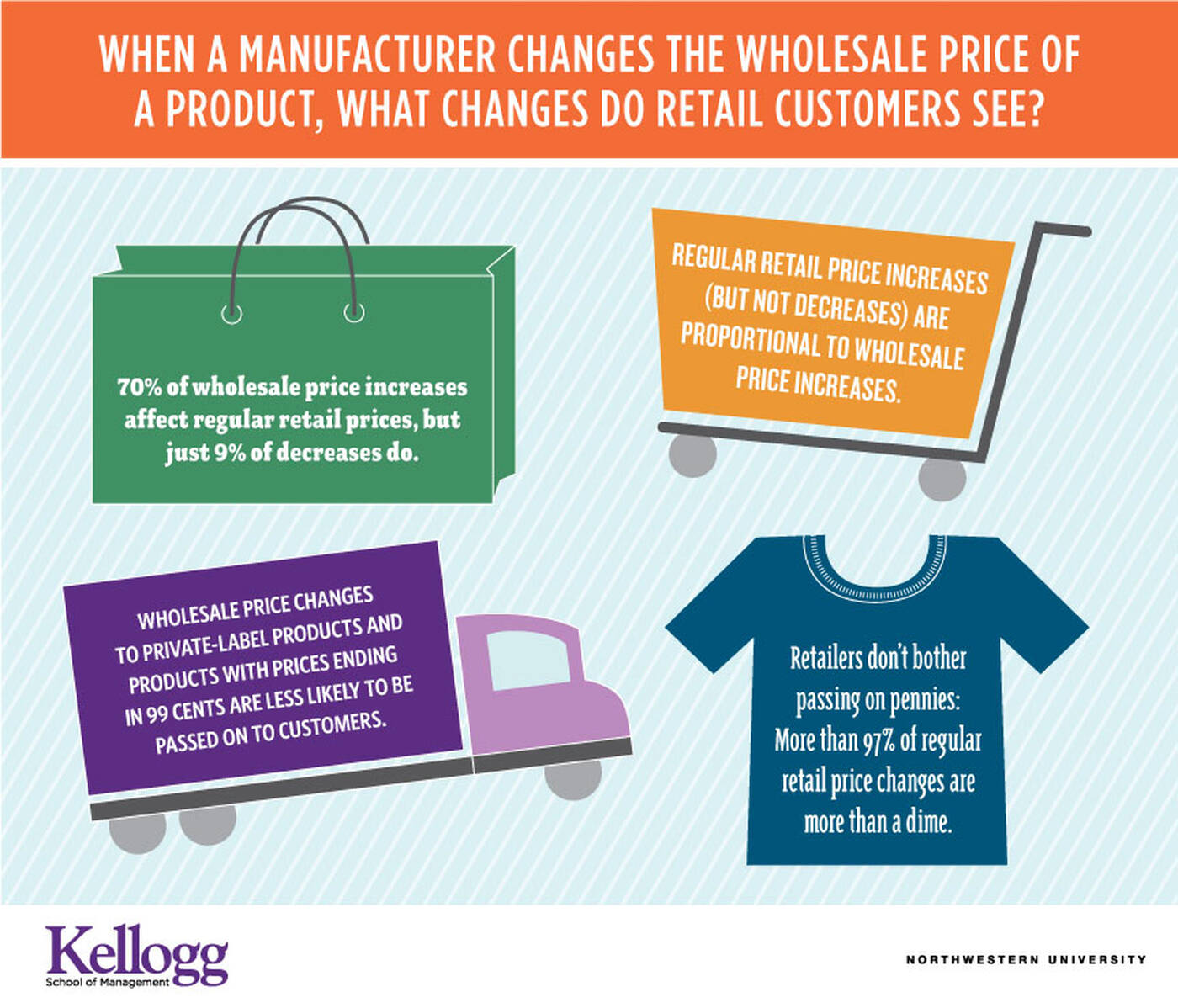

So what impacts whether a price will change? For one, managers are more likely to pass through a price change when wholesale prices go up. The difference is dramatic: retail prices rose after 70 percent of wholesale price increases—but fell after only 9 percent of wholesale price decreases.

A number of product characteristics also impact whether a price change is passed through. For example, managers are less likely to change the prices of private-label products relative to national brand products. Consumers often purchase private-label products based on their lower price point—so the retailer may want to keep the retail price steady in the face of a wholesale price increase, even if that means the retailer’s margin decreases.

Managers were also less likely to increase the prices of products with retail prices ending in 99 cents. This is because consumers perceive a $2.99 to $3.09 price hike to be much larger than a $2.89 to $2.99 one.

Researchers also investigated the magnitude of any retail price changes that occurred in response to wholesale price changes. They found that when managers increased retail prices, they did so roughly proportionally to the wholesale increase. But when they decreased retail prices, McShane says, there was “more of a flat adjustment down,” regardless of how large the wholesale price change was. Interestingly, the product characteristics that affect whether retail prices change did not seem to affect the size of the change.

Why do retail managers behave so differently in practice than they do in theory?

For one, managers might anticipate future price fluctuations. “If managers expect future wholesale price increases, they might forego lowering a price now only to raise it again a short time in the future,” McShane explains. Managers could also be wary of failing to meet margin targets or could be working to balance prices within a category. In addition, there are costs associated with changing prices. These costs, ranging from physically swapping out one price tag for another to updating software, differ from retailer to retailer, but they tend to make prices “sticky.”

Understanding how retail managers make pricing decisions has implications for manufacturers and wholesalers making their own pricing decisions. Though the current study suggests that wholesale price changes are often not passed through to consumers at all, manufacturers and wholesalers can still hold sway over the retail price. They just may need to take a more direct approach.

“If wholesalers want to affect the price consumers pay, they might want to consider attempting to influence promoted prices rather than regular prices,” McShane says. During Labor Day weekend, for instance, Coke or Pepsi might work directly with retailers to offer discounts, coupons, buy-one-get-one-free offers, or other forms of promotions.

“Wholesalers think a lot about what retailers are going to do in response to their price changes,” explains McShane. “Arranging offers like these takes the guesswork out of it.”

McShane, Blakeley B., Chaoqun Chen, Eric T. Anderson, and Duncan I. Simester. Forthcoming. “Decision Stages and Asymmetries in Regular Retail Price Pass-through.” Marketing Science.