Featured Faculty

Member of the Department of Managerial Economics & Decision Sciences faculty until 2018

John L. and Helen Kellogg Professor of Operations

Check out the Insight In Person podcast to hear Kellogg faculty and Barry-Wehmiller employees and executives discuss the company's leadership model.

We have all read the obituaries: American manufacturing is dead. The jobs have gone to lower-wage countries and they are not coming back. But while the number of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. has dropped significantly in recent years, manufacturing as part of GDP has remained strong due to improved productivity and increased automation.

So while the reports of its death may have been greatly exaggerated, American manufacturing is certainly going through something of a sea change. Fewer people are making more stuff. Companies that are thriving in this environment tend to be those where highly skilled workers are at a premium, or those that can reduce labor costs without hurting productivity.

“Most of the firms that have been successful in the U.S., or are staying in the U.S., are firms that are able to substitute capital for labor,” says Marty Lariviere, a professor of managerial economics and decision sciences at the Kellogg School. “Or the labor that they have is highly skilled, so the company is able to cross-train workers to do lots of things.”

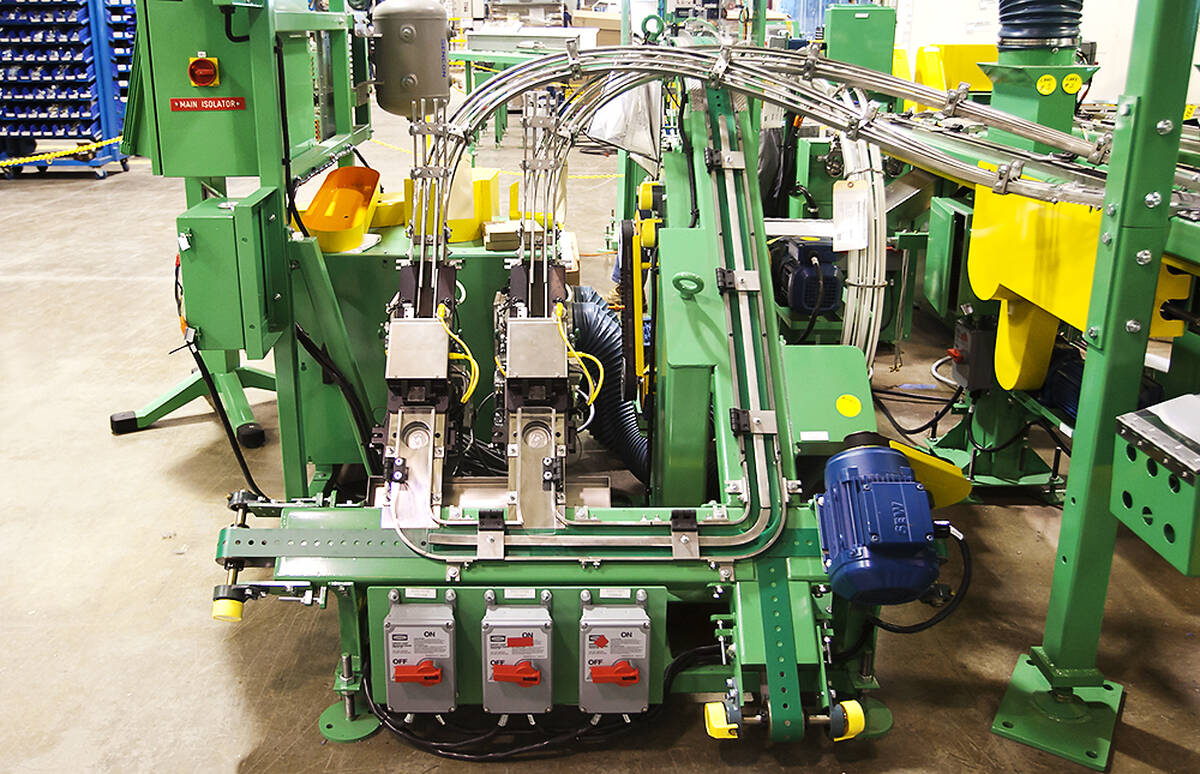

Barry-Wehmiller, a privately held manufacturer of technology consulting and packaging machinery, is dedicated to building just this sort of flexible, well-trained workforce. It is also boasts an employee-centric corporate culture designed to empower and inspire its 8000-plus employees. The resulting productivity improvements and lower turnover rates are good for business—but the focus of the company is as much on its team members as it is on the bottom line.

Freeing People Up to Lead

Perhaps nothing exemplifies Barry-Wehmiller’s commitment to an employee-centric culture as much as Barry-Wehmiller University, the company’s in-house leadership and communication institute. The university is the flagship of an extensive ongoing learning program throughout the company that focuses on personal fulfillment, recognition, leadership, and the benefits of continuous process improvement.

“We see the process of continuous improvement as being critical to translating what you believe to the front-line for associates, so that the life that they're living at work matches up to the vision that you have for your culture,” says Rhonda Spencer, the company’s chief people officer. “As an American manufacturing business you have to drive to that if you want to continue to survive. The biggest way that we can touch our people’s lives is by having a sustainable future in this business. We owe our people a vibrant future.”

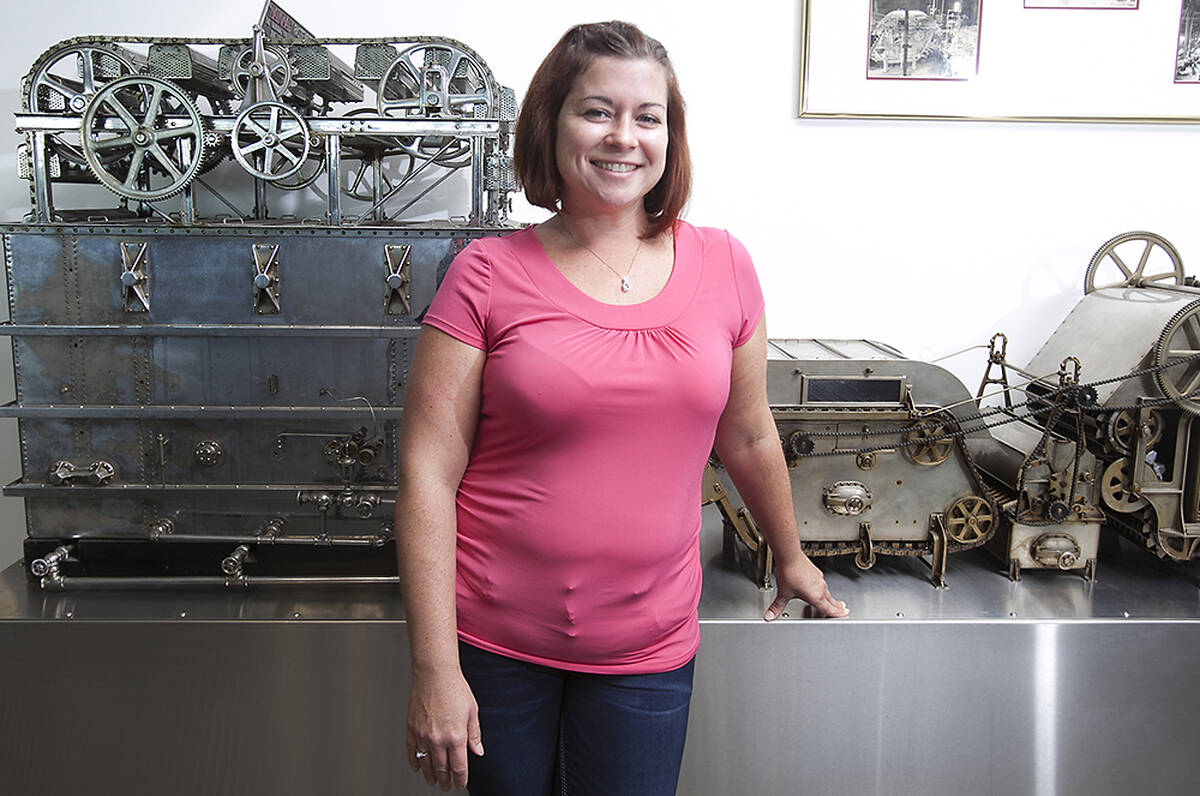

On the floor, the notion of employees-as-leaders manifests itself as “responsible freedom”—in other words, no micromanaging. “We've got the responsible freedom to make our own decisions and structure what we do the way that fits for us personally,” says Jenny Copanos, assistant controller at the company’s Romeoville, Illinois, facility. This freedom is not without its complications. “One struggle you may see is people having enough confidence in themselves to move forward with those decisions. It’s our responsibility as people and leaders to help each person see their full potential,” Copanos says. “It's very different from other organizational cultures. Some people are just not used to that freedom to do what they feel is right.”

“They are working in a field where at least stereotypically workers are looked at as just a cog in the wheel,” says Dylan Minor, a professor of managerial economics and decision sciences at Kellogg. “What gives this particular firm a competitive advantage in their industry is that it's not the norm to really value people and try to make a great place to work. They've made the commitment—that clearly is not profit-driven—in how they're developing that culture.”

Eating Last, Gaining Trust

“There’s a military expression, ‘Leaders eat last,’” Barry-Wehmiller CEO Bob Chapman says. Instilling that mindset across the business’s 10 operating companies has included a combination of rhetoric and action. During the recent financial crisis, production across the company slowed. The leadership organized a furlough program that included everyone in the company from the top down. This unpaid leave was evenly distributed as a way to retain employees for the long term, when demand was expected to return. The furlough program contributed to a culture of trust between frontline employees and the C-suite.

“It's one thing to convince your workers that you trust them by the things that you say, but what really matters is what you actually do,” says Minor. “The fact that all levels of leadership were also willing to take the financial hit so they could keep everyone employed over time showed that they really did care about their workers.”

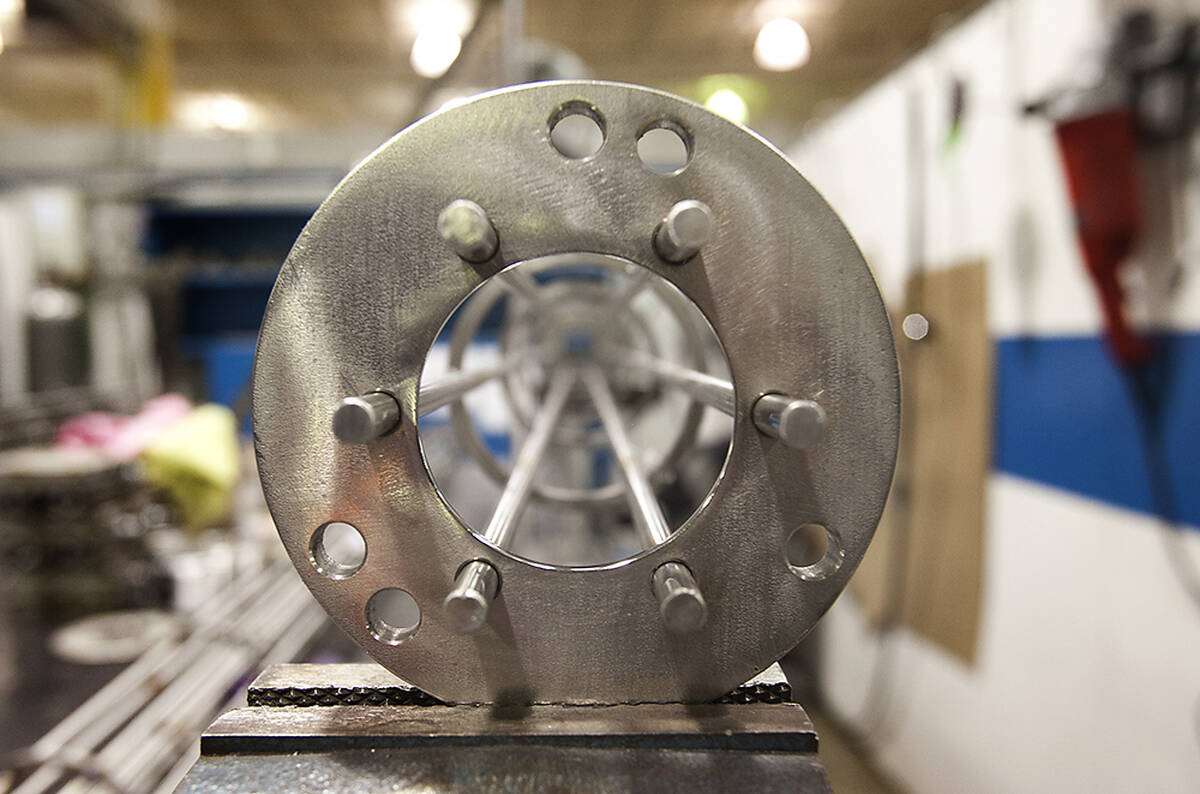

When Barry-Wehmiller acquired its Romeoville, Illinois, facility in 1999, more than half of the factory floor was dedicated to fabrication and machine shop. “Based on a self-evaluation of our business a few years after acquisition, our leadership team determined that we have two key areas that bring value to our customers: customized engineering and mechanical and electrical assembly,” says Vince Jones, operations manager at the Romeoville facility.

The company developed its factory focus on mechanical and electrical assembly and developed its network with fabricators and machine shops in the area around Chicago. “With this network in place, we started cross-training fabricators into assembly,” Jones says. “Today, we have a flexible workforce that can be moved in and out of fabrication and assembly based on the business needs.”

This flexibility counteracts some of the operational risk that accompanies a high retention rate. Lariviere notes that in a changing market, “If you have effectively tenured people, it’s pretty hard to turn on a dime and completely reskill an incumbent set of people.”

Who’s Next?

Another risk of putting a premium on retention is that it can lead to an aging workforce and the possibility of losing large amounts of institutional knowledge through retirement. Building strategies and systems for capturing and transferring employee knowledge can be expensive and may not always pan out.

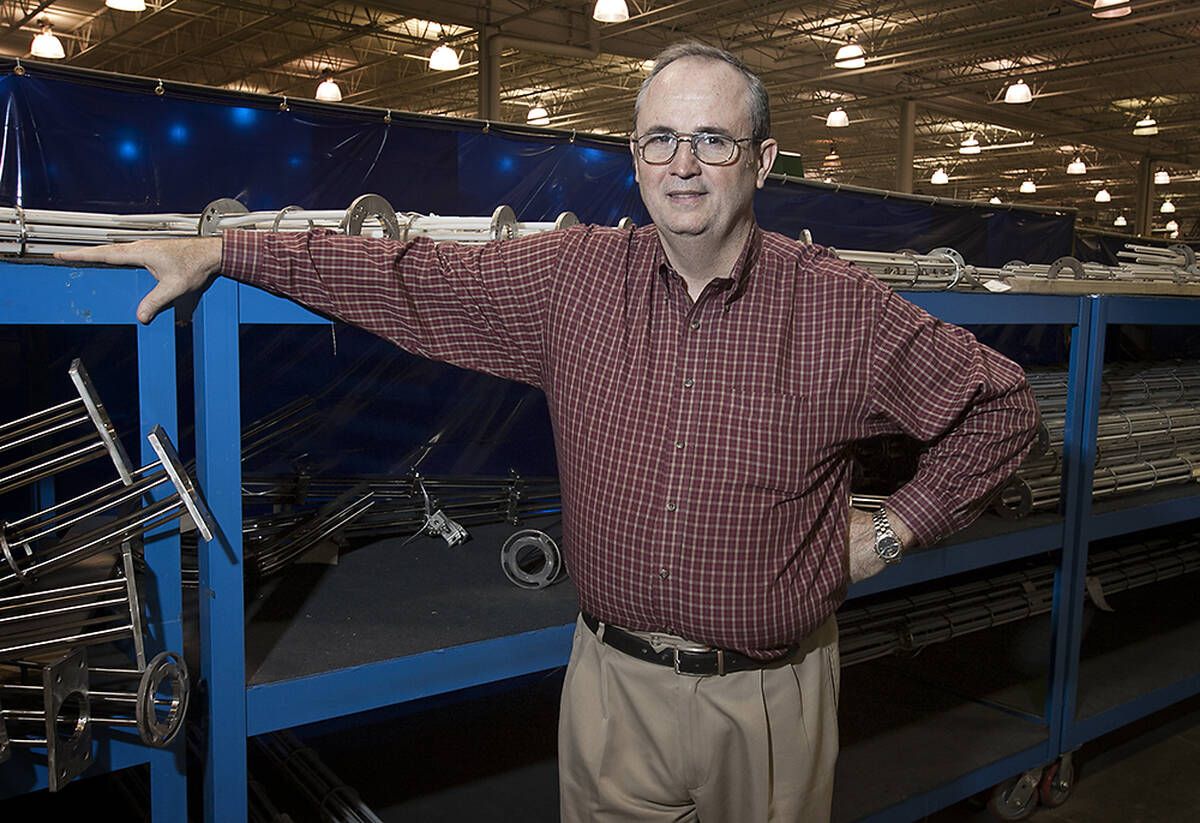

“Our average age and experience for our team members on the shop floor is 52 years old with 20 years of experience,” says Vince Jones. “What happens when they all retire? We are working on developing competencies in leadership roles that will need to be filled within the next five to ten years. Our experienced workforce has developed a legacy that we want to continue and pass on to the next generation.”

Even with the training systems Barry-Wehmiller has in place, this will be costly. “Having some sort of apprenticeship program that brings people along is expensive because you can't be assured that everybody that you take on is going to make it through,” Marty Lariviere says. “You've got to start with a wider funnel and have some way of trimming that down, and there's no guarantee that once you've brought someone on and trained them, they actually want to stick around if they've got other opportunities.”

But if any company is suited to deal with these challenges, it may be Barry-Wehmiller. And whatever it learns, it will not hesitate to share with the broader business community. “We have a lot of very proactive things in place where we are making every effort to share what we've learned with the world,” Rhonda Spencer says. “There's no downside to that. We're not at all worried that competitors or anyone else is going to get a hold of this great secret about treating people well.”

Editor's Note: To hear more about Barry-Wehmiller and employee-centric manufacturing, head to the Insight In Person podcast featuring Dylan Minor and Marty Lariviere, professors of managerial economics and decision sciences at the Kellogg School.

Slideshow photographs: Eddie Quiñones