Featured Faculty

Professor of Management and Organizations; Management and Organizations Department Chair

Yevgenia Nayberg

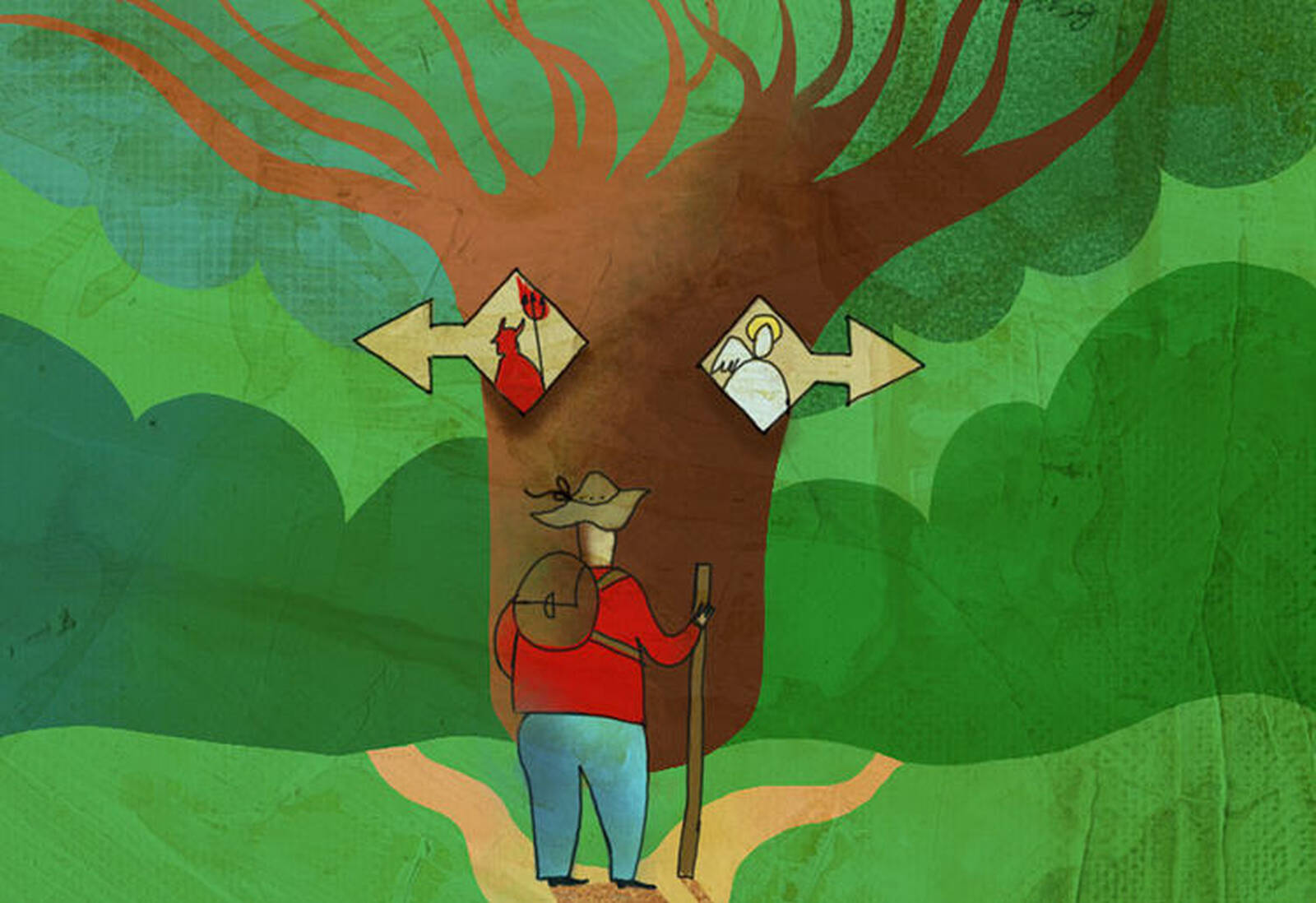

What makes one person act heroically at a critical moment while another wavers?

Kellogg’s Maryam Kouchaki was struck by stories of people who sprang into action when faced with such a choice—chasing down a mugger, for example—who later said there hadn’t been any alternative.

“Even though they did the most amazing thing, it wasn’t like they felt that they deliberated. They felt like they had no choice,” says Kouchaki, an assistant professor of management and organizations, who studies moral behavior—why we engage in it, why we fail at it, and how we think about it.

It is not just the heroes among us who view moral decisions this way. In fact, new research from Kouchaki and coauthors finds that across cultures, when people view a particular decision as being moral in nature, they don’t feel like they are making a choice at all, and they pay less attention to alternative courses of action.

The finding surprised Kouchaki. Given that morality is so important to self-image, she imagined that “when you do something good, you want to take credit for it.” And the more you view your moral choices as choices, the more credit you could give yourself.

“Their sense of freedom has been constrained and it has a spillover effect for your actual behavior.”

But that is not what she and her coauthors Isaac Smith of Cornell University and Krishna Savani of Nanyang Technological University found. Instead, people “don’t try to get credit for their moral choices as much as they potentially could.”

It makes a certain kind of sense to Kouchaki. “Morality is all about defining what’s right to do,” she says. Moral behavior is often viewed as a set of responsibilities and obligations. Think about the words we use for moral behavior, she says, where we often refer to what we “ought” to do.

“You see the link in the language we use,” Kouchaki explains.

Morality and Decisions

To explore how people make moral decisions, the researchers devised several related studies. In the first, they recruited 200 online participants and asked them whether they viewed one of four issues (abortion, marijuana use, gun control, or recycling) as moral in nature.

Then, they presented study participants with a scenario in which they had to make a choice related to one of the four issues—for instance, voting on a firearms ban, or accepting a friend’s offer to smoke marijuana. Finally, they asked participants to rank, on a scale of one to seven, how constrained they felt in making that choice: “I had to vote yes (or no) on the firearms ban; I didn’t have a choice.”

It turned out that people who viewed a particular issue as moral experienced a lower sense of choice when making a decision related to that issue, as compared to people who did not view the issue as moral.

The team wanted to make sure this finding was true across cultures and didn’t just apply to highly individualistic Americans. So they repeated the same study with 200 online participants from India. Instead of asking about gun control or abortion, they picked an issue that was more culturally specific: eating beef, which is prohibited in many Hindu traditions.

As in the first study, participants were asked if they viewed eating beef as a moral issue. Then they were presented with a scenario in which a friend offered them a beef samosa.

Although the cultural issue was different, the result was just the same: Indians who viewed eating beef as a moral issue experienced a lower sense of choice when deciding whether to accept the offered samosa.

The Effect of Choice Constraint

The researchers next looked at how feeling restrained can affect other aspects of behavior.

They knew from a 2009 study by other researchers that people who feel physically constrained tend to seek variety in other ways. For example, if the aisles of a store are narrow, your purchases will be more varied than if the aisles are roomy. When pressure is put on your autonomy, the thinking goes, you’ll try to assert it in other ways.

The researchers wondered whether the psychological constraint of morality might have a similar effect. If you lack a sense of choice in moral decisions, will you seek more variety in other, unrelated decisions?

To test the idea, they repeated the original study, asking participants whether they viewed using marijuana as a moral issue. Then participants were presented with a scenario in which they could accept or refuse a friend’s offer to smoke. To measure variety-seeking behavior, the researchers then asked participants to select seven pieces of chocolate from a set of seven different flavors.

The more moral that participants found the issue of marijuana to be—meaning the more constrained they felt in their ability to make a choice—the more variety they sought when picking chocolate.

For Kouchaki, it was further proof that moral decisions don’t really feel like choices at all. “Their sense of freedom has been constrained and it has a spillover effect for your actual behavior,” she says.

Inside the Decision-Making Process

In the final study, the researchers set out to understand what was happening as people mulled their moral choice. How much and how long did they contemplate their choice? Did they really not contemplate alternative options, or did they only report a sense of constraint after making a decision?

To get inside participants’ heads, the researchers used a tool that allowed them to monitor how long participants contemplated each option by recording how long their mouse hovered over each choice on the computer screen.

Participants repeated a study similar to the first one: they were asked whether they considered a particular issue moral, given a scenario about that issue, and then ranked their sense of choice from one to seven.

The team found that participants who viewed an issue as moral hovered for less time on the option they did not choose as they made a decision. This allowed the researchers to rule out the possibility that participants weighed both options equally, but only reported a lower sense of choice later. Rather, viewing a decision as moral seemed to truly influence participants’ sense of making a choice.

Moral Choices in the Real World

So why, if people don’t view moral choices as choices, do they so often misbehave?

In the real world, it gets complicated, Kouchaki says.

“People might know the right or wrong thing to do,” she says. “Still, we may fall for temptation, because there are other competing motivations present that are strong.”

On a hectic day, it is much easier to pitch your aluminum can in the trash can next to you than it is to walk to the recycling bin downstairs. There is usually a cost, even a small one, to making the moral choice, and such costs are not generally present in lab studies.

For Kouchaki, the findings were both surprising and, she confesses, a little disappointing.

She had always thought her moral decisions were the result of conscious, deliberate thought, not just reflexive action.

“I wanted to take credit,” she says. “But apparently not! This actually proved my intuition was wrong.”