Innovation Entrepreneurship Jan 4, 2021

5 Ways Established Companies Can Overcome Internal Hurdles to Innovation

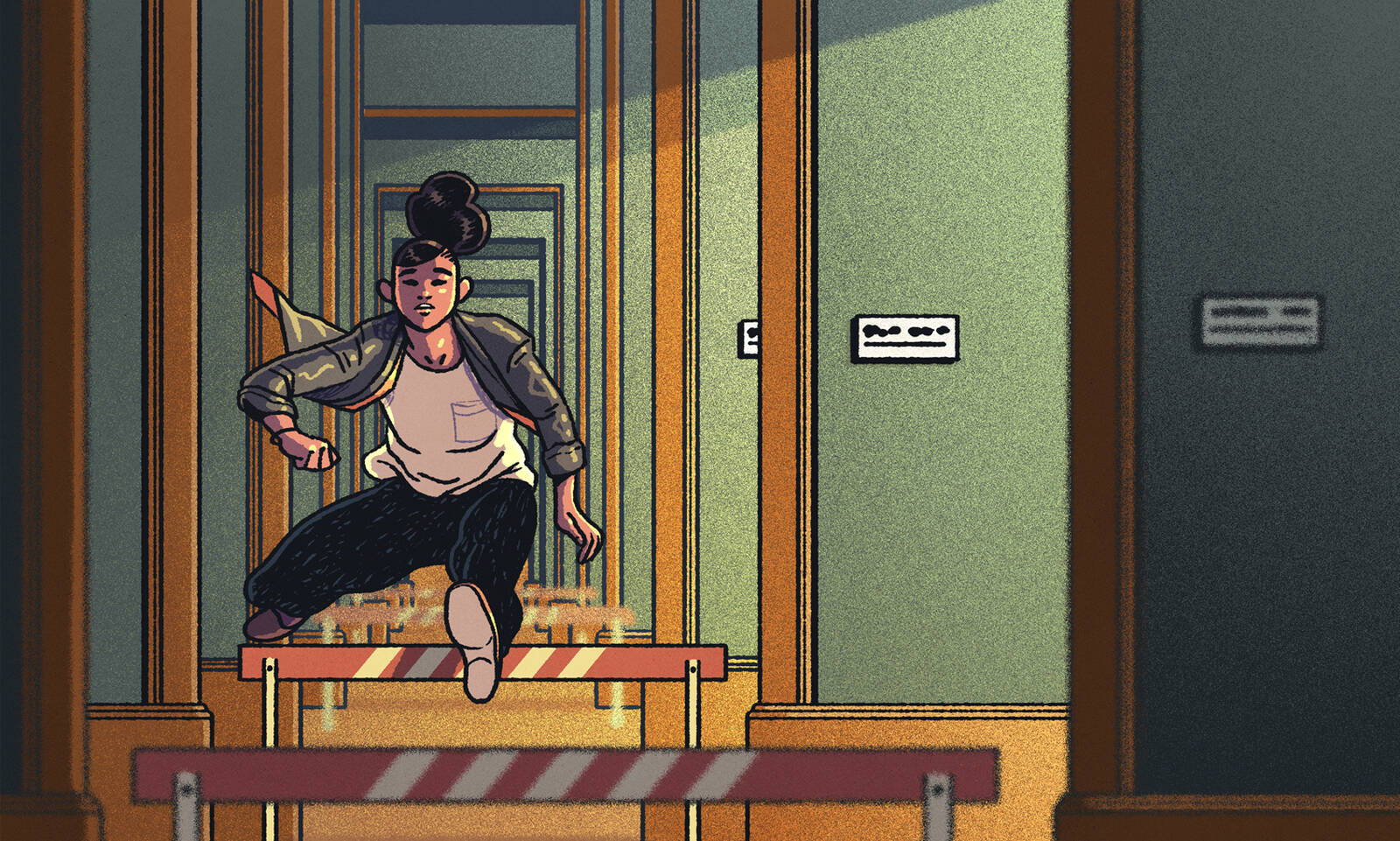

Narrow the scope of your brainstorming sessions. And find the right champion for your project.

Michael Meier

Rapid innovation can be tougher to achieve at established companies than at startups. After all, when the drive to fail fast and keep iterating has to coexist with long-standing operations, there is bound to be some friction.

But intrapreneur teams are critical to keeping up with the ever-increasing pace of disruption—particularly in an environment made even more unstable by the global pandemic.

“In the past, if you got the lead and you controlled the market, you could do so for a long time. Now, we’re seeing that disruption-cycle shorten,” says Jeffrey Eschbach, an Adjunct Professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Kellogg.

So in an effort to ride that trend and continue innovating, established companies are often tempted to think and act just like startups. But, according to Eschbach, this strategy can lead to unexpected issues in the corporate environment. In order to get the most out of their innovation efforts, they will need to adapt their approach.

Eschbach, a seasoned intrapreneur and entrepreneur, outlines five ways that intrapreneurs can overcome some of the most common internal hurdles—and take advantage of unique opportunities too.

Respect Existing Customer Relationships

Customer research is essential to product development. This means innovation teams need to be able to work closely with customers to gather feedback throughout the design process. However, there are a number of internal stakeholders who need to be considered too. In an established company, customer contact is typically the role of the sales team, and they often have existing customer relationships that must be respected. When drawing customers into the research process, then, there’s a risk of stepping on the sales team’s toes.

“You as an innovation team could send the wrong message to customers,” Eschbach says. “For example, I’ve seen teams solicit feedback on a prototype and leave customers thinking that their suggestions are what the company plans to do, rather than that they were just collecting data.”

Before your customers mistakenly assume that the cool storyboards and prototypes they discussed with the innovation team will soon materialize, it is critical that communication between teams, and with external stakeholders, is frequent and clear. Without this clarity, sales and account-management teams may be put in the awkward position of having to walk back promises to customers.

Eschbach recommends that companies establish a clear communication system that integrates the sales team into the customer-research process. This can be as simple as alerting the account manager before engaging a particular client or asking them for a “friendly” contact who’s willing to share feedback without building up unrealistic expectations. If a sales team is especially cautious about the appearance of overselling the company, the innovation team can even work with agreed-upon consultants to approach clients and ask questions.

This integration will lead to fewer mix-ups, which may make sales teams more willing to collaborate with their innovation colleagues in the future. Putting sales managers into conversation with customers as part of the research process also increases their investment.

Don’t Fight Other Stakeholders, Include Them

Other internal teams, including engineers and designers, provide opportunities to unlock new improvements. These groups are often left out of customer-research efforts—or are only brought into the process after problems emerge. Including them from the start can avoid later disconnects and motivate the teams.

“Innovation teams and product managers may come back from meeting with a client and say, ‘Hey engineers, trust me, we’ve got to do this with the prototype,’” Eschbach says. “And the engineers think, ‘Did the client really say that? I don’t quite think that’s really true.’”

Including tech teams in customer-facing conversations, or scheduling joint field trips to observe how customers use products and prototypes in the wild, can be eye-opening for everyone.

“After seeing the problem firsthand, their ability to create something on target, along with their motivation, increases tremendously. They think, ‘yeah, we’re actually solving a real problem. This isn’t just one laundry-list item that the product managers are coming up with. The customer really is telling us that this is a pain point.’”

Getting a glimpse of the end users’ environment and hearing what they actually want to accomplish helps engineering teams gain a much sharper focus on what to design. Team members who join field research often go from doubters to advocates within their own teams, helping to get buy-in on initiatives from their colleagues.

Use the Resources at Your Disposal

Yes, established companies may face more friction—but they also start the innovation process with some distinct advantages. After all, over time, they have amassed product lines, internal platforms, data sets, and a customer base. Eschbach recommends that innovation teams put these hard-earned resources to use in the innovation process.

“You’re still bringing all the same methodologies, all the same techniques for gathering information,” Eschbach says, “But you have stuff the startups don’t have. If you have a great, responsive customer base, go talk to them—with, of course, the blessing of your sales team.”

“Find a senior leader who’s willing to say, ‘I need this in my road map, or I need this in my product line.’ You want to get people on board with a high-level mandate to innovate. They’ll give you a little bit of cover.”

— Jeffrey Eschbach

One example comes from the airline industry, where an innovation team was tasked with researching whether customers would pay for extra leg room. The team identified the check-in kiosk as a resource where customers provide information on their buying preferences. Adding a screen that inquired about their willingness to upgrade to a roomier seat saved the money of refitting jetliners for a perk customers may be willing to do without or may not be willing to pay for.

“By doing this very simple, lightweight test, they obtained feedback from the exact point where customers would be making the purchase,” Eschbach says. “A normal startup would not be able to test something like that because they wouldn’t have the kiosks.”

Don’t Be Tempted by Blue-Sky Thinking

Intrapreneurs often kick off ideation phases with brainstorming sessions where “anything goes” and there are “no wrong answers.” Such sessions hold strong appeal. What better way to welcome input and gain buy-in across various departments?

But open-ended brainstorming sessions tend to create little of value, Eschbach says. Rather than spurring actionable ideas, discussions tend to range from off-the-mark to obscure, leaving participants frustrated.

“You’ve got to have the guard rails in place which actually open things up in a productive way,” Eschbach advises.

The solution, he says, is to focus conversations on specific areas where customers have concerns.

“You might ask the team to aggregate what’s really going wrong and hurting customers in the field,” Eschbach says. “Then you ask them to narrow down on how to help with that issue. It might sound counterintuitive, but the narrower the pain point, the easier it is to expound, talk about, and explore it.”

Eschbach has participated in a wide range of brainstorming sessions in his career. But one session during his time at Motorola stands out for being particularly effective. His innovation team was looking for ways to design communications tools for firefighters when they are on the scene of incidents.

Before the brainstorm started, the team interviewed firefighters to get a better understanding of the conditions they encounter when battling a blaze: they are under stress, they are often wearing gloves, their vision may be impaired by smoke, and they may not know the location of their colleagues.

Then, rather than starting from scratch with an “anything goes” discussion, the innovation team built their brainstorm around those parameters.

“We came up with solutions on the tech side to help them be more context aware,” he says. “We realized we could use temperature sensors to identify which firefighters are nearest the danger, and then prioritize their audio and video feeds back to the commander.”

Having guardrails in place prevented the team from wasting too much time on ideas that would have been unworkable. “We initially thought we could roll out a text option for them, but in a fire scene with smoke, what they really need is speech automation so that they can hear what’s going on instead of trying to read while they’re fighting a fire,” Eschbach says. “So many innovations emerged because we restricted the scope, not because we left it wide open.”

Find a Champion in Senior Leadership

With complex, established organizations facing so many competing priorities, having a senior leader who can provide vision and champion intrapreneurship endeavors will be crucial to sustaining their impact.

“Find a senior leader who’s willing to say, ‘I need this in my road map, or I need this in my product line,’” Eschbach says. “You want to get people on board with a high-level mandate to innovate. They’ll give you a little bit of cover.”

A C-suite champion can help intrapreneurs clear the lane if salespeople resist having innovation members speak with customers. They can also help clarify the importance of company-wide engagement in innovation efforts.

“Engagement is the real win,” Eschbach says. “Getting it depends on having the right person who is really committed to it. It’s not just about making sure a particular project gets support but making sure that you as an innovation team are. When the folks above you get what you’re doing and why, that can go a long way.”

Innovation teams may need to be, well, innovative about finding their C-suite champions. One idea Eschbach recommends is building “pitch days” into regular quarterly meetings. These events help normalize intrapreneurship activity and get high-level buy-in on projects.

“You can now bring the directors, the VPs, and others who may have budget authority into a space to hear the different pitches. When they latch onto one, now you’ve got your cover. You’ve got your champion who says, ‘I saw 20 pitches. I love that one, let’s go and make it happen.’”

“By formalizing this process, when the inevitable internal red tape and naysayers emerge, you’ll have a visible mandate to point to. And if push comes to shove, there’s now someone in your corner with the motivation and authority to help keep your efforts moving forward.”

Susan Margolin is a freelance writer based in Boston.