Operations Oct 4, 2018

A Counterintuitive Way to Keep Shelves Stocked and Prices Down

New research suggests how to improve supply-chain efficiency and avoid “inventory runs.”

Riley Mann

Ask your local liquor store how much of a certain beer they sell, and you will likely get similar answers from week to week.

“They might sell twelve six-packs one week, then eleven, then twelve, then thirteen,” says Robert Bray, an associate professor of operations at Kellogg.

But ask the brewer who makes that beer how much they ship weekly, and the story gets more complicated. It would be normal for a brewer to be responding to orders to ship 500 cases of beer for three weeks straight and then zero the next week, Bray says. “The brewer is going to see really volatile changes.”

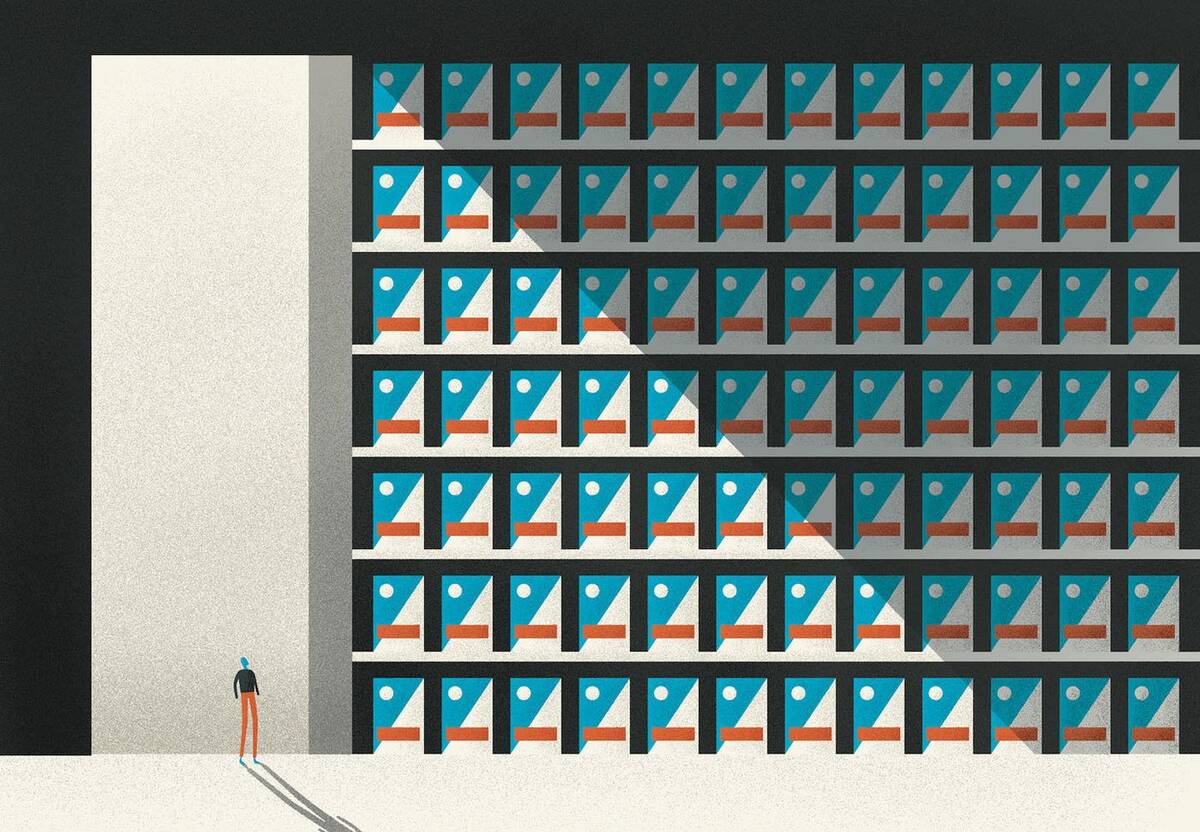

This phenomenon, which happens in all kinds of industries, is what experts call the “bullwhip effect.” As demand moves up the supply chain, from consumers to stores to suppliers, it becomes more and more unpredictable—just as a tiny flick of the hand morphs into a wild, forceful smack as it travels down the length of a bullwhip.

But the bullwhip effect is not merely a concern for retail managers and suppliers. When suppliers and distributors are unable to predict demand, the supply chain becomes less efficient.

“And who’s ultimately going to pay for that? The consumer,” says Bray, since those inefficiencies are passed on to shoppers in the form of higher prices and sometimes product shortages.

But what causes the bullwhip effect—and can at least some of the price hikes and shortages be alleviated?

A new study by Bray, along with Lehigh University’s Yuliang Yao and Tongji University’s Yongrui Duan and Jiazhen Huo, tested one theory behind the effect.

Analyzing data from a major Chinese grocery chain, the team found the first-ever hard evidence of what they call “inventory runs.” When retailers see that a supplier is on the verge of running out of an item, they order excessive amounts of that item in hopes of keeping their shelves well stocked—in the same way that customers of a failing bank mount a “bank run” to get their money out before the bank becomes insolvent.

By the researchers’ estimate, these inventory runs are responsible for 11 percent of the bullwhip effect. But there is a simple way for suppliers to keep these runs from destabilizing their business. If they hide their inventory levels from retailers, then they can prevent runs, enabling them to better estimate demand for their wholesale goods.

“This is something we can fix,” Bray says.

Understanding the Bullwhip Effect

In the world of supply chains, everyone is trying to predict the future.

“I order inventory today because I think I’m going to be able to sell it tomorrow,” Bray says. “So the more volatile the environment, the harder it is to place economic bets.”

To see just how disruptive this volatility can be for a supplier, Bray says, imagine that you are the manager of a car factory who receives zero orders one month and 500 the next. “One month you have to furlough all your workers and shut down the factory, and the next month you have to pay overtime,” he explains. “You’d rather it be stable—250 each month.”

Bray became fascinated with the bullwhip effect as a PhD student at Stanford, taking courses from Hau Lee, who first theorized the phenomenon in 1997. (“He’d bring an actual bullwhip and snap it in class,” Bray recalls.)

Lee’s groundbreaking paper theorized four different factors that might be driving the bullwhip effect. The most powerful factor was what is called “batching”—the fact that while liquor stores can sell individual six-packs of beer, warehouses only sell them by the pallet-load. As such, each store might go months without placing an order as they work through their pallets, but then suddenly need a truck-load of beer.

“When the distribution center looks like it’s about to stock out, the stores all increase their order quantities. They’re like, ‘Oh man, the distribution center’s about to run out of deodorant—I better order a lot more before it runs out.’”

However, batching was not the whole story. Lee had theorized that something called “ration gaming” might also contribute to the bullwhip problem. Ration gaming is the idea that stores could amplify their orders in periods of scarcity to increase their likelihood of getting some product before the supplier runs out.

Yet in two decades of studying the bullwhip effect, no researcher had ever discovered empirical evidence that ration gaming was actually happening. “There have been people who have looked for it, but nobody has found it,” Bray says.

Bray wanted to keep looking. “The data required to demonstrate the existence of ration gaming is hard to come by,” he says. But when he got access to one of the most comprehensive supply-chain samples ever studied, he thought, “I thought I might have a fighting chance of finding it.”

Why Managers Game the System

The researchers procured extremely detailed data on the sixth-largest supermarket chain in China. The data included three years of daily orders of more than 3,000 products from 73 retail stores, all of which got their products from a single distribution center in Shanghai.

Importantly, each store manager placed her store’s order on a computer system that also let her see the current inventory in the distribution center’s warehouse, meaning she could incorporate that information when deciding how much of a product to order.

“And what we show is, there are these inventory runs,” Bray says. “When the distribution center looks like it’s about to stock out, the stores all increase their order quantities. They’re like, ‘Oh man, the distribution center’s about to run out of deodorant—I better order a lot more before it runs out.’”

The researchers also showed that these inventory runs were significantly contributing to the bullwhip effect for this chain. Using statistical techniques, they simulated what would have happened if the stores had not been able to see the inventory level of the distribution center.

In that scenario, the distribution center would have seen 11 percent less fluctuation in its day-to-day orders.

These inventory runs make things harder for suppliers and potentially drive up prices for consumers. So why did the store managers, who place the daily orders, consistently orchestrate them?

Bray emphasizes that the managers were acting completely rationally. After all, when supplies dipped to their lowest levels, only 36 percent of stores had their orders fulfilled, in first-come, first-served order—and these supply shortages regularly lasted for a week or longer. That means that stores that did not commit inventory runs, or that did so too late, risked running out of a hot product.

And since a manager’s pay is partially based on her store’s sales and profits, empty shelves mean she is leaving money on the table.

“We interviewed the store managers,” Bray says. “They had no sense of shame about this. It didn’t even occur to them to be circumspect. They’re just thinking, ‘My job is to manage this store. I would be shirking my duty if I wasn’t keeping track of the distribution center’s inventory level.’”

Improving Supply-Chain Efficiency

The supplier bears the brunt of these inventory runs, seeing surging demand when supply is at its lowest, which makes it all the more difficult to predict how much product the store managers will want from week to week.

As Bray puts it: “They kick them when they’re down.”

But there is a simple solution to this problem: suppliers can stop sharing their inventories with retailers. “If I hide this data, they don’t know when I’m down,” he says.

Bray notes what an unusual prescription this is. When it comes to supply chains, or economics in general, sharing information typically leads to better, more efficient outcomes for everyone.

“I think this might be the very first paper that comes up with a cost for showing information in the supply chain,” he says.

For the most part, stores and suppliers have learned to live with the bullwhip effect. After all, much of the problem is rooted in batching—and, despite the problems that come with high-volume orders, it just does not make economic sense for suppliers to ship their products in smaller numbers.

But in a world where predicting the future is the name of the game, it matters that a full 11 percent of the bullwhip effect is due to inventory runs, which can be prevented.

“That other 89 percent, there’s nothing you can do about it,” Bray says. “This is the 11 percent you can actually do something about.”