Featured Faculty

Polk Bros. Chair in Retailing; Professor of Marketing

Charles H. Kellstadt Chair in Marketing; Professor of Marketing

Michael Meier

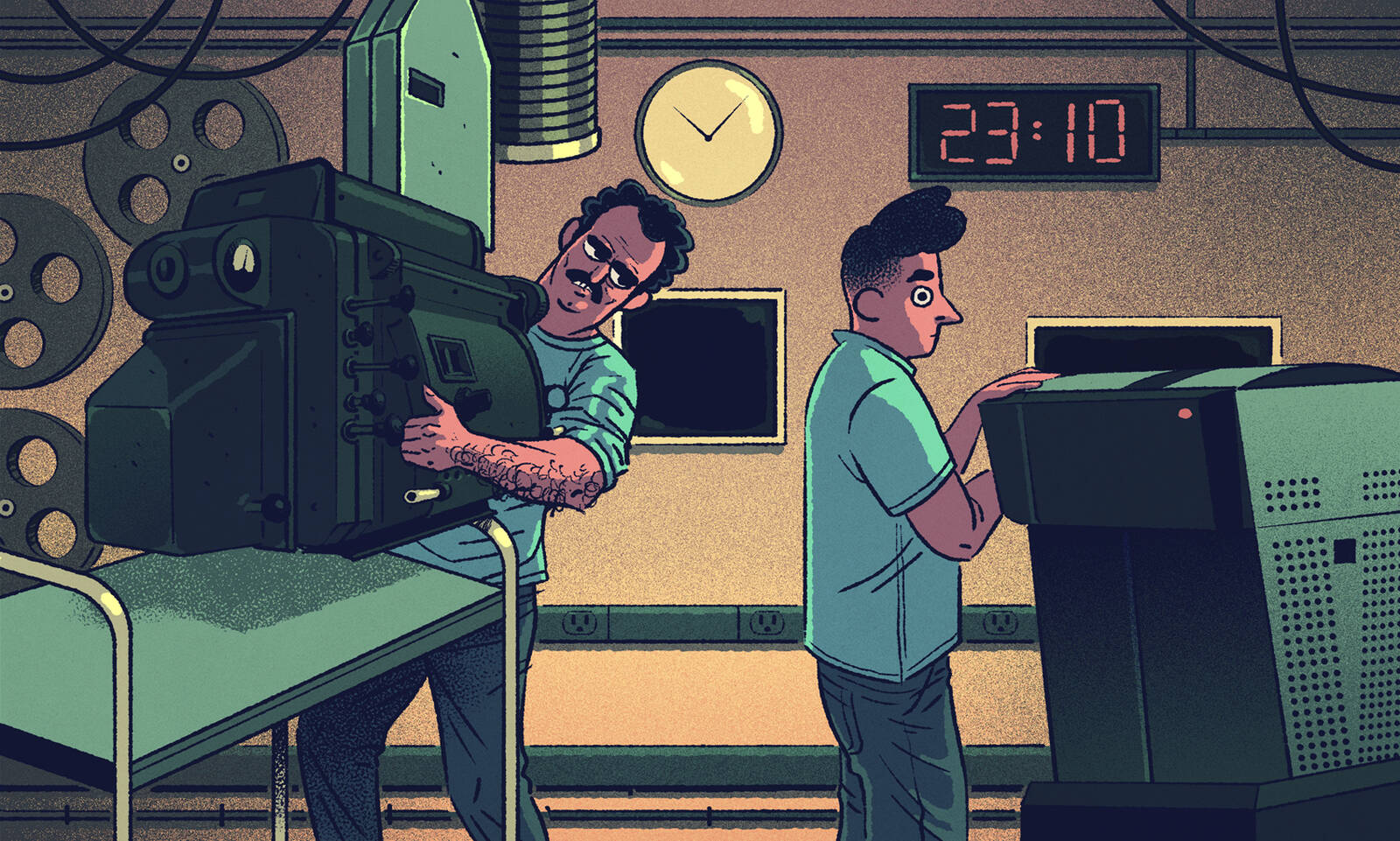

Leading up to its release, the 2009 movie Avatar was promising to be a record-shattering hit. In order to capitalize on the blockbuster to the fullest extent, movie theaters around the world got rid of their creaky old film projectors and purchased sleek digital replacements. While the new projection technology had been available for nearly a decade, it took the promise of a digital smash hit to convince theaters to adopt it at a large scale.

Before long, digital filmmaking and digital projection had become the industry standard. While it was an expensive investment for theaters, it allowed them to be more nimble in what they screened. How did this massive transformation change moviegoing? A new paper by Kellogg faculty suggests digitization changed theaters’ screening decisions and allowed them to better meet consumer demand.

“It’s not a surprise that this transition took place: physical film was particularly inefficient. It’s heavy and it’s expensive,” says marketing professor Eric Anderson. “What was more surprising was how this affected the assortments [of movies] offered to consumers.”

Anderson, along with associate professor of marketing Brett Gordon, and Kellogg PhD. student Joonhyuk Yang, now a postdoc at Stanford GSB and an incoming faculty member at University of Notre Dame, focused on South Korea, which boasts the highest per capita annual movie attendance of any country and is the fifth largest international box-office market for U.S. movie studios. They found that the switch from digital yielded both an overall increase in the variety of movies being shown in theaters and in the number of screens showing the most popular movies at peak hours.

“[Theaters] fought the change as much as they could until it was shown to them very clearly that the economics made sense.”

— Brett Gordon

“With digital, it’s easier to have time for niche films, because one employee can manage all the screens in a theater, and they can effortlessly switch between one movie and another with the push of a digital button,” Gordon says. “On the flip side, digital technology also gives the theaters more flexibility to stream the big blockbusters even more. It was interesting that we found these two effects together.”

The very first digital film, Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace, was screened in Los Angeles in 1999. But it took time for theaters to switch over, in part because the new equipment was so expensive. A single digital projector could cost as much as $150,000—an eye-popping sum for a theater with eight screens to convert. As a result, Gordon says, theaters “fought the change as much as they could until it was shown to them very clearly that the economics made sense.”

Initially, there was little urgency. From 1999 until the early 2000s, relatively few films were released in a digital format—mostly big-budget offerings, such as Star Wars

and Toy Story 2. The financial crisis of 2008 also slowed the transition by making it difficult for theaters to borrow the capital they needed to upgrade their equipment. But Avatar “acted as a rallying point to get the industry to transition, which James Cameron pushed very hard for,” Gordon explains. From that point on, the conversion process picked up momentum; 90 percent of movie screens worldwide had gone digital by 2015.

Converting came with a host of benefits: the film era required the creation of costly physical copies of movies. The number of times per day a theater could screen a hit movie was limited by the number of copies they had. Film also posed logistical challenges: each movie required several reels that were heavy and hard to manipulate, and the process of switching between movies on a projector was time-consuming. As a result, theaters tended to show only one movie per screen each day. Digitization changed all that, making it effortless to offer more movie variety to consumers.

South Korean theaters faced similar constraints and pressures to convert as their U.S. counterparts. In fact, it was the very same film, Avatar, that prompted South Korean theaters to invest in digital technology on a large scale. By 2013, every chain theater screen in the country boasted a digital projector.

The research gave a starring role to a dataset from the Korean Film Council, which tracked daily showtimes and attendance for every chain theater in the country from 2006 to 2016. The data also included the format—film or digital—of each film shown. (The data didn’t include theater-level revenue data, so the researchers weren’t able to study how the shift to digitization affected profits.)

This detailed information allowed Gordon, Anderson, and Yang to infer when every screen in every theater converted from film to digital, based on the first date a digital film was shown on that screen. The researchers also gathered South Korean box-office data that allowed them to distinguish between the most popular blockbusters and smaller, more niche films.

It was “a unique database that shows the birth of digital and the death of film,” Anderson says. “You get to see the gradual progression of every theater in South Korea making that transition.”

Because the transition from film to digital was both gradual and nonrandom (for example, larger chains with more revenue were able to convert sooner than smaller ones), the researchers had to develop a way of statistically isolating the effects of digitization. Their statistical model, which controlled for factors such as variable seasonal demand in moviegoing, allowed them to see how digitization changed theaters’ screening decisions over time.

The model revealed two distinct periods: from 2006 to 2010, when fewer films were released in digital format and fewer theaters had converted, and from 2011 to 2016, when digital projectors became ubiquitous and all movies were released in digital format.

In the earlier part of the transition to digital, the overall variety of movies screened in South Korea actually decreased. The trend was driven by large theaters with five or more screens, which had mostly converted to digital projection. With indie movies mostly still released only on film, the same few digital-format blockbusters played on repeat, resulting in a 13 to 21 percent decrease in variety. “There weren’t that many digital movies to show, so theaters were sort of stuck with them, and this crowded out niche movies that were still in film format,” Anderson explains.

But in the later era, the true effects of the digital transformation became apparent and overall movie variety increased. Smaller theaters with four or fewer screens saw the most noticeable increases, of about 11 percent. In larger theaters, the researchers observed, the percentage of screens devoted to blockbusters increased during weekend hours, but decreased on the weekdays, resulting in greater variety during these less-popular times.

In other words, theaters prioritized blockbusters during peak periods and “offered slightly more variety or more niche films during off-peak periods,” Gordon explains. “It’s a more efficient use of their screen space, given the ebb and flow of consumer demand.”

The overall increase in movie variety after digitization came as a surprise to the researchers. “I thought you’d see big movies have a greater presence, and consumers would have less variety but greater access to those blockbusters,” Anderson says.

But the data told a more nuanced story in which digitization proved to be something of an equalizer.

Pre-digitization, “the cost of physical prints was squeezing out small, entrepreneurial indie films, and so those types of films didn’t have access to the market,” Anderson says. Post-conversion, the economics changed: digital movies were less expensive, and there was no logistical impediment to showing a niche movie only once or twice per day, making the investment worthwhile.

Of course, since March of 2020, few films have found theatrical audiences, with screens around the world going dark due to COVID-19. Consumers are now able to stream new releases from the comfort of their own sofa. Will movie theaters meet the same unhappy fate as the many music, book, and movie-rental retailers hit hard by the shift to digital?

Not necessarily, Anderson argues. These retail stores were more vulnerable to a digital transformation because, at least for some consumers, there was little meaningful difference between physical and digital versions of the products. What’s more, digitization yielded increased selection, essentially rewarding customers who shopped from home instead of in person.

But theaters offer “a lot more in terms of services than the Blockbusters or Tower Records of the world,” he points out. They allow you to “get out of the house, which we’re all eager to do, you’re with other people, and you have amenities”: a bag of buttery popcorn, a reclining seat, 3D glasses, beer, wine, and food. When it becomes safe for them to open their doors again, “theaters are going to have to compete on those service dimensions.”