Featured Faculty

Associate Professor of Operations

Ruslan Momot was a Visiting Assistant Professor of Operations from 2021 to 2022

Riley Mann

Internet platforms like Uber, Angi, and Postmates have made it easier than ever for sellers to connect with customers—for a small convenience fee, of course. But once those connections are made, it should also be easy to avoid ever paying a convenience fee again. After all, a homeowner could use Angi to find the perfect handyman—and then deal directly with him from then on, instead of using Angi. Economic theory predicts that both buyers and sellers have a strong incentive to engage in “disintermediation”—to cut out the middleman, in other words. But how often do they actually do it?

“It’s a pressing topic because more and more of our business nowadays is moving onto these platforms,” says Robert Bray, an associate professor of operations at Kellogg. For platform businesses, “disintermediation is the worst possible thing: it’s literally one set of [their] customers training another set of customers to depart the system. Once you’ve taught someone to disintermediate, you might lose them for good.”

And while it might be hard to conjure sympathy for the likes of Uber or Postmates, Bray adds that not every platform business is a venture-capital-funded behemoth. He and his colleagues Ekaterina Astashkina and Ruslan Momot (of the University of Michigan) and Marat Salikhov (of Russia’s New Economic School) looked for evidence of disintermediation on an app that connects local housecleaners with clients in Moscow. “It’s actually offering a useful service, but they really don’t have that many degrees of freedom to keep people in the network,” he explains. If disintermediation were common, “I don’t think the platform would be viable.”

Luckily for Moscow housecleaners—but less so for prevailing economic theory—the researchers found no evidence of disintermediation at all, a result they called “disquieting.”

“This is an area that’s received a lot of theoretical attention,” Bray says. “If you were to model all agents as perfectly rational, it’s very clear that everyone’s incentivized to disintermediate as fast as possible. People are saying, ‘this ought to happen.’ Why can’t we find it?”

One reason disintermediation is hard to find is that “by design, it’s kind of sneaky,” Bray explains. “People who do it are doing it in a way that the platform can’t really see.”

For instance, consider an app that facilitates several successful transactions between a service provider and a customer—and then sees both users suddenly depart the platform. Did they conspire to cut out the middleman, or did they simply have no more business to conduct? Usually, there’s no way for the platform to tell the difference.

But the Moscow-based housecleaning app had one key feature that let Bray and his colleagues get around this problem: it tracked users’ locations by default, even when they weren’t actively using the app. (This was a common practice in smartphone apps prior to 2019, when Apple’s iOS 13 began encouraging users to opt out of default tracking.)

“We set out looking for disintermediation. We wanted to find it. But we just couldn’t.”

—

Robert Bray

These data, which were anonymized by the researchers, provided an unusually transparent way to observe any possible disintermediation. The app recorded the time when a housecleaner was scheduled to perform a particular job, plus the particular location of the residence where the cleaning was performed. But because the app was always passively tracking the housecleaners’ locations, the researchers could also see if they returned to clients’ residences without a job being formally scheduled through the app. Such visits would be compelling evidence that disintermediation had occurred.

“Maybe a housecleaner does two or three cleanings for a resident, and then the relationship [on the app] just ends. Now the question is: Did they disintermediate or not?” Bray explains. “We answered this in the most obvious way possible—within the next month or so after the suspicious termination of the relationship, we looked to see if the cleaner returned to that address. The scene of the crime, as it were.”

The researchers also considered the app itself to be “ripe for disintermediation” for several reasons. For one, the platform added significant markups to housecleaners’ fees—sometimes as high as 40 percent. Moreover, unlike U.S. customers, Moscow residents at the time had “no cultural precedent” for hiring service workers through formalized, commission-charging agencies—it was much more common to conduct such transactions under the table. (According to the researchers, this shadow economy comprises more than 40 percent of Russia’s GDP.) Plus, for anyone wishing to avoid the app’s fees, the in-person nature of housecleaning work would make it a snap to arrange future appointments without relying on the platform.

In other words: if there were ever a perfect trap for catching middlemen-cutters in the act, Bray and his colleagues would have found it. “We set out looking for disintermediation. We wanted to find it,” he says.

“But we just couldn’t.”

What did they find? Not just an absence of evidence for disintermediation—which would be disappointing but expected, given how hard the phenomenon is to observe at all—but actual evidence of absence.

This proof that disintermediation wasn’t happening—think of it as the opposite of a smoking gun—came from comparing several sets of location data from the housecleaning platform.

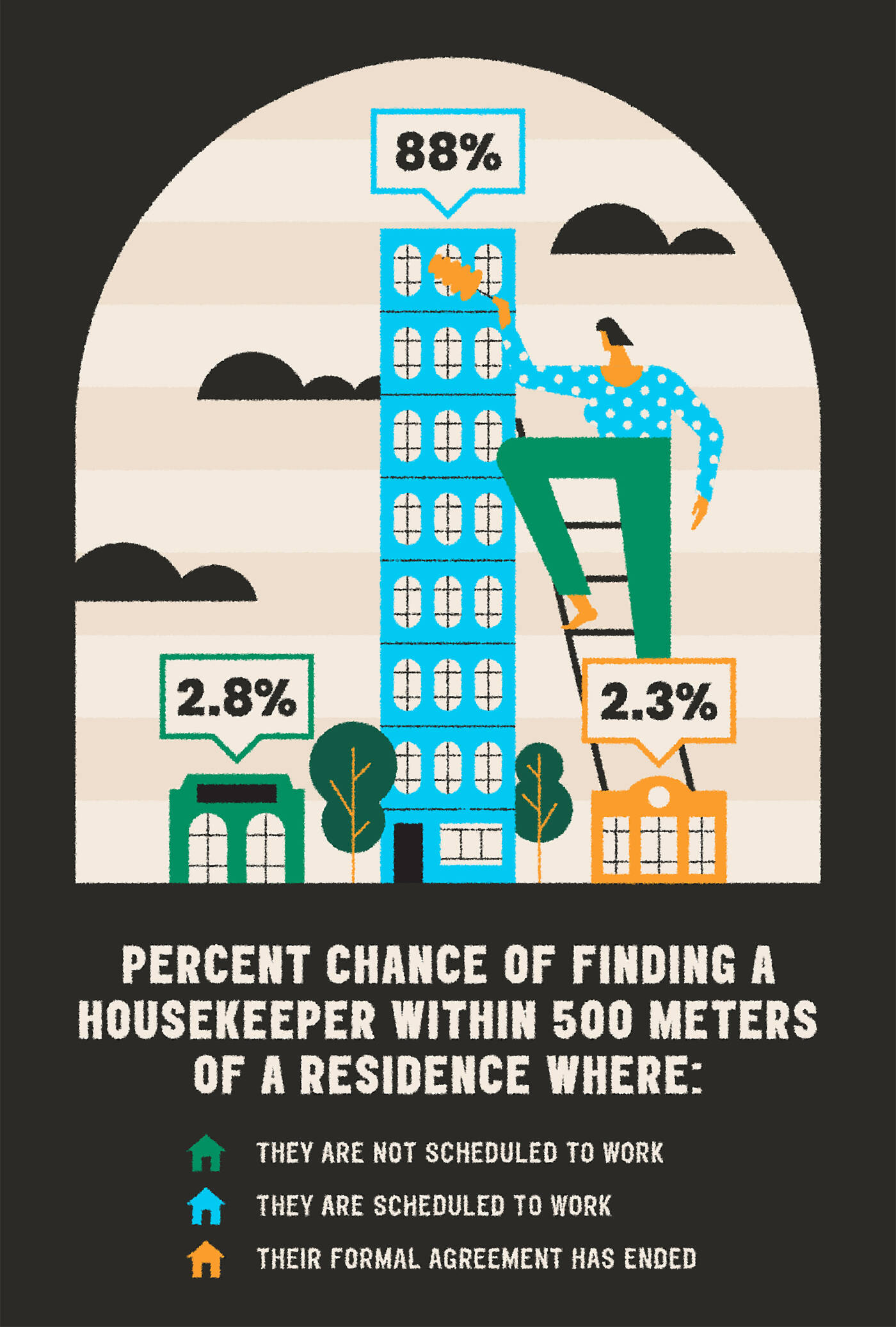

The first set plotted the likelihood that a housecleaner would be within 500 meters of a job site when that job was formally scheduled via the app. In this “working sample,” housecleaners showed up when and where they were expected to: the probability that they were within 500 meters of the house they were supposed to clean was about 88 percent. A second set, called the “non-working sample,” measured the opposite effect: in between scheduled jobs, there was less than a 3 percent chance that they’d be near a house that they officially cleaned at least once in the past. These two datasets established a clear portrait of “good behavior” for the app’s users.

But the “un-smoking gun” came from a third set of location data—one showing where housecleaners were likeliest to go in the months after their final scheduled job, as the app continued to passively track them. This is the time period when disintermediation would likely occur. This third dataset turned out to look almost exactly the same as the “non-working sample”: there was only about a 2 percent chance that housecleaners got within 500 meters of a house they’d previously cleaned.

In other words: there was no sneaking around, no cutting out the middleman. If there had been, the researchers would have seen it in the location data—just as clearly as if it were security footage from a resident’s building.

“It’s probably the first negative result on this topic,” Bray says. “It’s extremely difficult to estimate platform disintermediation, and all the literature is saying it ought to be present. We found very strong evidence that it’s not.”

Bray cautions that no single paper can definitively debunk economists’ current understanding of disintermediation. But he does say that his team’s results suggest that the phenomenon “is a problem in theory, but not in practice” for many platforms.

“In theory, platforms should dissolve [because] every single time that you and I transact, we should always agree to screw over the platform,” he explains. “But we’ve learned that, actually, the convenience of working with the platform is often worth the twenty or thirty percent cut that they take. It’s just easier. So platforms might not need to take the countermeasures [against disintermediation] that theory would suggest.”

Although their study didn’t formally investigate why users of the housecleaning app chose not to cut out the middleman, the researchers did offer some speculative explanations. For one, inviting a stranger into your apartment to clean it “is a very intimate thing, so you might want a little bit of security” that a platform provides, Bray says. “Anyone who’s going to the app is already specifically looking for a non-disintermediated relationship.”

As for the platform’s marked-up fees, “Russia has pretty high income inequality—which means the people well-off enough to use the app can probably afford the few extra rubles.”

As for why his results contradict economic theory, Bray has a hunch about that as well. “There’s some psychological bias [in the field] that says positive results are interesting, and negative ones are not,” he says. This “desk-drawer” bias means that studies showing something failing to happen—like disintermediation, in this case—are less likely to be submitted to journals for publication in the first place.

“I think it’s important sometimes to be willing to publish a negative result,” he says. “That’s the only way truth will come out. We’re saying, ‘We thought we were all on the same page [about disintermediation], but here’s something that shows we’re not.’ No paper is definitive, of course. It just makes the picture a little bit more complex.”

John Pavlus is a writer and filmmaker focusing on science, technology, and design topics. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

Astashkina, Ekaterina, Robert Bray, Ruslan Momot, and Marat Salikhov. 2023. "A Disquieting Lack of Evidence for Disintermediation in a Home-Cleaning Platform." Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4244111 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4244111