Featured Faculty

MUFG Bank Distinguished Professor of International Finance; Professor of Finance; Faculty Director of the EMBA Program

Michael Meier

Who among us hasn’t dreamed—even just in passing—about starting life afresh in some far-flung place?

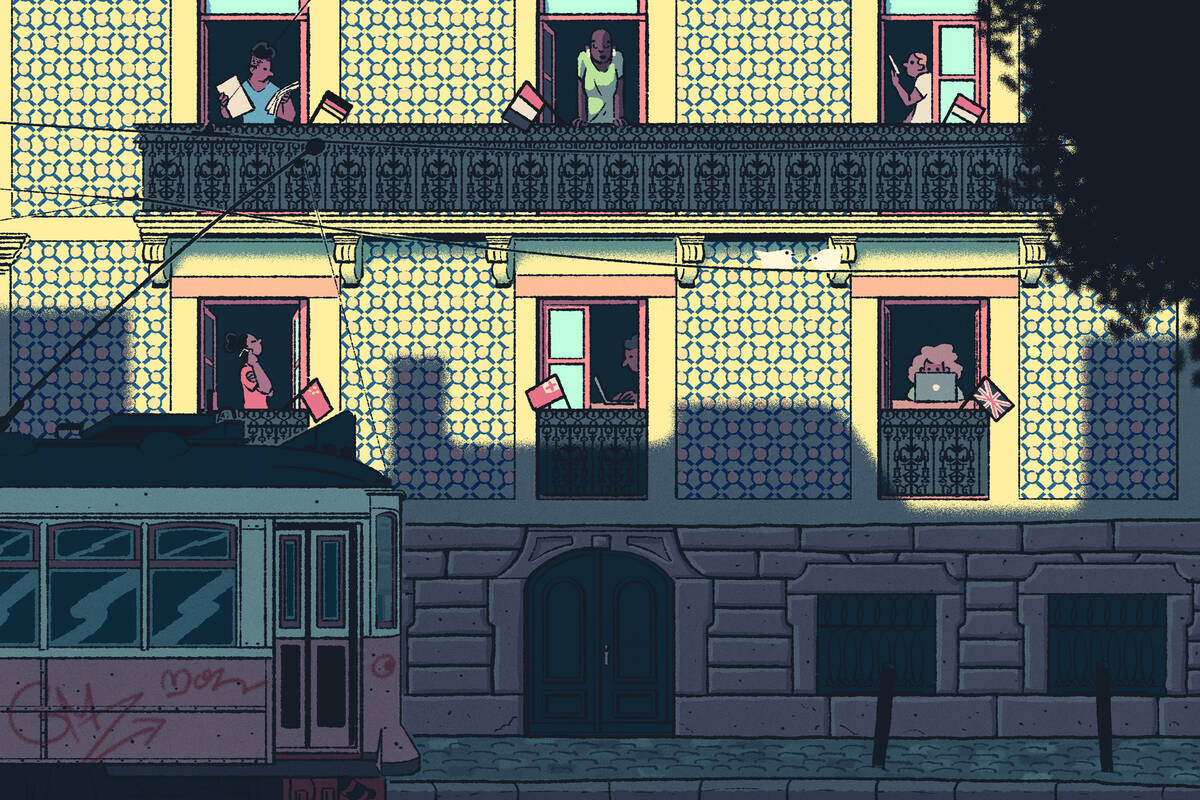

In recent decades, the decreased cost of air travel and the rise of remote work have made that dream a reality for some. Popular global cities, including Paris and Venice, have seen a surge of foreign arrivals from wealthy countries, laptops in hand and stars in their eyes, settling in for months or longer.

Among locals, reactions are mixed. Affluent foreigners patronize local stores and restaurants, but bring with them increases in rents, traffic, and congestion, as well as cultural changes.

Sergio Rebelo, a professor of finance at Kellogg, knows this struggle firsthand. A native of Portugal, he’s watched the country’s capital city, Lisbon, grapple with a tide of Americans, French, and others wanting to live there.

“Lisbon is a beautiful city. It’s being transformed by a huge influx of foreign residents and tourists,” he says. Downtown Lisbon is now filled with souvenir shops and restaurants catering to foreigners and “making the city less appealing to the local population.”

Governments around the world have responded to the increase in wealthy foreign residents in various ways. Most policy interventions focus on housing, because rents and property values are so dramatically and immediately affected by the new arrivals. Some countries, convinced the good is worth the bad, have actively encouraged foreigners with housing subsidies; others have taken the opposite approach, outright restricting would-be expats from buying homes or heavily taxing their property purchases. But which strategy is best?

In a new paper, Rebelo and coauthors João Guerreiro of UCLA and Pedro Teles of the Catolica-Lisbon School of Business and Economics answer this question. They find that neither subsidization nor taxation of foreigners’ home purchases is the best way to address the challenges. Instead, the researchers propose, governments should adopt a kind of Goldilocks approach: tax capital gains on property sales for everyone and use the revenue to help offset the harms caused to locals.

This tax-and-transfer approach provides “a win–win solution,” Rebelo says. “I think a lot of policies that are implemented are kind of lose–lose, because you prevent the foreigners from coming in, but then you also don’t obtain those potentially large capital gains.”

For their model, Rebelo and his colleagues envisioned a metropolis divided into a city center and a periphery. Wealthy foreign residents prefer the city center; locals choose where to live and work based on a variety of factors, including personal preference and commute time.

An influx of foreign residents causes housing prices to increase in the city center. This rise benefits locals who own property and can sell or rent it to foreigners. The resulting capital gains create what the researchers call the “foreign resident surplus”—essentially, the extra funds that foreigners introduce into the country’s economy.

But there’s also an economic downside: locals who remain in the city center now pay higher rents and have less money to buy other things. Some may choose to relocate to the periphery and endure longer commutes that make them less productive.

“We started the study with a somewhat agnostic view, ... so we were a bit surprised at the result, which says, ‘Look, it’s efficient to let foreigners come, and then if there’s other problems like traffic congestion, you should fix them separately.’”

—

Sergio Rebelo

So, is the economic upside greater than the downside?

Yes, the researchers discovered. Countries receive enough gains from the foreign resident surplus to outweigh the costs borne by locals. That’s why policies discouraging wealthy foreign arrivals aren’t optimal—because countries leave so much money on the table. Encouraging foreigners with housing subsidies, meanwhile, tips the scales too far in the other direction.

In other words, by taxing capital gains on property, governments can collect some of the foreign-resident surplus and use it to address the new issues local renters face. “This policy is relatively simple,” Rebelo says. For example, “if I live in one of these large cities that has a lot of foreigners, my rent might be subsidized.”

Of course, relocation to the periphery has social costs. People may be less productive and spend more time in traffic because of congestion. The benefits of density highlighted by urbanologists like Jane Jacobs, such as enhanced learning opportunities through close interaction, may also diminish. To mitigate these drawbacks, the government could implement location-based taxes and subsidies that vary depending on where people reside and work.

The researchers also considered other factors, such as remote work. When workers have the option to work from home, living in the periphery as opposed to the city center has fewer downsides.

Rebelo says he and his colleagues were struck by their findings. “We started the study with a somewhat agnostic view, but we heard from many people that foreign residents are causing a lot of problems for locals, and therefore, their housing purchases should be taxed,” he says. “So we were a bit surprised at the result, which says, ‘Look, it’s efficient to let foreigners come, and then if there’s other problems like traffic congestion, you should fix them separately—for example, charging for vehicle traffic during peak hours.’ But it’s inefficient to impede a transaction that is so valuable.”

He thinks the research also highlights some long-term approaches that countries can take as they consider how to adjust to their new realities. For example, converting underused city-center offices into housing creates much-needed space in key areas. “Over time, you see more hotels to accommodate tourists, you see more residences that are designed for foreigners, and you see pure office buildings and factories move out of the city center,” Rebelo explains. Moving offices out of the city center may also reduce the displacement of locals in those neighborhoods or even make the periphery more attractive to commuting workers.

In Paris, for instance, some companies moved their offices to outlying districts, making way for tourists and other foreigners in central districts. It’s a different city—but that’s not necessarily a bad thing. After all, Rebelo says, “cities are like a living organism, and they transform organically over time.”

Guerreiro, João, Sergio Rebelo, and Pedro Teles. 2023. “Remote Work, Foreign Residents, and the Future of Global Cities.” NBER Working Paper No. 31402.