Organizations Policy Jul 1, 2023

How to Prepare for AI-Generated Misinformation

“We have to be careful not to get distracted by sci-fi issues and focus on concrete risks that are the most pressing.”

Lisa Röper

The explosion of artificial-intelligence systems has offered users solutions to a mind-boggling array of tasks. Thanks to the proliferation of large-language-model (LLM) generative AI tools like ChatGPT-4 and Bard, it’s now easier to create texts, images, and videos that are often indistinguishable from those produced by people.

As has been well-documented, because these models are calibrated to create original content, inaccurate outputs are inevitable—even expected. Thus, these tools also make it a lot easier to fabricate and spread misinformation online.

The speed of these advances has some very knowledgeable people nervous. In a recent Open Letter, tech experts including Elon Musk and Steve Wozniak called for a six-month pause on AI development, asking, “should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth?”

Regardless of the pace of advances of these AI systems, we’re going to have to get used to a good deal of misinformation, says William Brady, professor of Management and Organization at the Kellogg School, who researches online social interactions.

“We have to be careful not to get distracted by sci-fi issues and focus on concrete risks that are the most pressing,” Brady says.

Below, Brady debunks common fears about AI-generated misinformation and clarifies how we can learn to live with it.

Misinformation is a bigger issue than disinformation

Brady is quick to draw distinctions between misinformation and disinformation. Misinformation is content that’s misleading or not factual, whereas disinformation is strategically created and deployed to deceive audiences.

Knowing the difference between the two is the first step in assessing your risks, Brady says. Most often, when people worry about generative AI’s potential harm, they fear it will lead to a sharp rise in disinformation, he notes.

“One obvious use of LLMs is that it is easier than ever to create things like disinformation and deepfakes,” Brady says. “That is a problem that could increase with the advent of LLMs, but it’s really only one component of a more general problem.”

Although deepfakes are problematic because their intention is to mislead, their overall penetration rate among total online content is low.

“There’s no doubt that generative AI is going to be one of the primary sources of political disinformation,” he says. “Whether or not it’s actually going to have a huge impact is more of an open question.”

Brady says that problems are more likely to surface in the perpetuation, rather than the ease of producing, misinformation. LLMs are trained in pattern recognition from scanning billions of documents, so they can exude authority while lacking the ability to discern when they are off base. Issues arise when people get misled by small errors that AI produces and trust it like they would information coming from an expert.

“LLMs learn how to sound confident without necessarily being accurate,” Brady says.

Does this mean that misinformation will exponentially increase the more we use generative AI? Brady says we can’t be sure. He points to research that shows that misinformation on social media platforms is small—some estimate as low as 1–2 percent of the overall information ecosystem.

“The idea that ChatGPT is suddenly going to make misinformation a bigger problem just because it will increase the supply isn’t empirically validated,” he says. “The psychological factors that lead to the spread of misinformation are more of a problem than the supply.”

The problem behind misinformation is also us

Brady believes that perhaps the greatest challenge with misinformation isn’t only due to unfettered advances in technology, but also with our own psychological propensity to believe machines. Brady says we may not be inclined to discount AI-generated content because it’s cognitively taxing to do so. In other words, if we don’t take the time and effort to look critically at what we read on the internet, we make ourselves more susceptible to believing misinformation.

“The psychological factors that lead to the spread of misinformation are more of a problem than the supply.”

—

William Brady

“People have an ‘automation bias,’ where we assume that information generated by computer models is more accurate than if humans create it,” Brady says. As a result, people are generally less skeptical of content created by AI.

Misinformation spreads when it resonates with people and they share it without questioning its veracity. Brady says that people need to become more aware of the ways that they contribute to the creation and spread of misinformation without knowing it. Brady calls this a “pollution problem.”

“The problem of misinformation tends to be on the consumer side—with how people socially share it and draw conclusions—more than by generating their own messages,” Brady says. “People believe what they read and expand upon it as they share. Really, they’ve been misled and are amplifying it.”

Get educated

Realistically, we can’t wait for regulatory oversight or company controls to curb misinformation, Brady says; they’ll have little impact on how content is created and distributed. Given that we can’t reel in AI’s exponential growth, Brady says that we need to learn how to become more aware of when and where we may encounter misinformation.

In an ideal world, companies would have an important role to play.

“Companies have to take responsible interventions based on the products they’re putting out,” he says. “If content was flagged, at least people can decide if it is credible or not.”

Brady envisions something similar being applied for misinformation and generative AI. He is in favor of online platforms helping users detect misinformation by labeling generative AI–produced content. But he knows that it doesn’t make sense to wait for tech companies to roll out effective controls.

“Companies are not always incentivized to do all the things that they should, and that’s not going to change in our current setup,” he says. “But we can also empower individuals.”

Getting users to develop situational awareness of the most common scenarios when misinformation is likely to surface can make misinformation less likely to propagate.

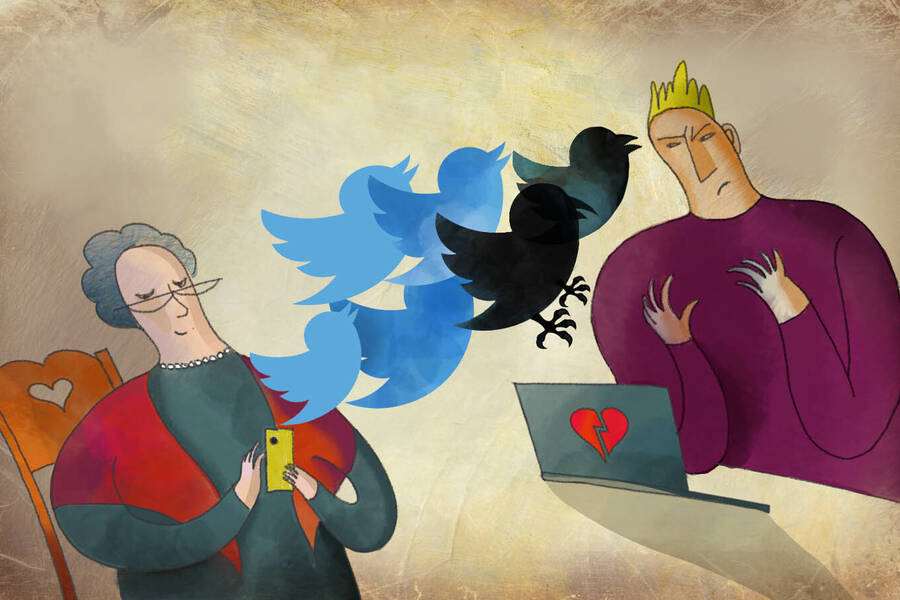

Since older adults tend to be the most susceptible to misinformation, providing basic education such as digital-literacy training videos or a gamified website for adults who are not as internet savvy as their Gen-Z counterparts could go a long way to tamping down online misinformation. These efforts could include developing public-awareness campaigns to make people aware of the role algorithms play in overpromoting certain types of content, including extreme political content.

“It’s about educating people about the contexts in which you might be most susceptible to misinformation.”

Susan Margolin is a writer based in Boston.