Marketing Data Analytics Strategy Dec 7, 2015

How We Shop Differently on Our Phones

What’s in your cart? Depends on the device you are using.

Yevgenia Nayberg

Consumers have come to love their mobile devices—that much is certain. But how does the technology shape their shopping behavior?

“Mobile shopping is no longer a future trend. It is happening now,” said Rebecca Jen-Hui Wang, a marketing Ph.D. candidate at the Kellogg School. Though the importance of mobile shopping is widely recognized, and private companies undoubtedly have their own data about mobile orders, few academic researchers have looked at how customers’ habits change when they pick up their iPads and smartphones.

Until now. In recent research, Wang and her coauthors—Lakshman Krishnamurthi, a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School, and Edward Malthouse of Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism—find that mobile technology has very distinct advantages for retailers. But it also has distinct disadvantages.

It generally does not lead people to search out new items, they found, or to carefully weigh their options. When customers shop with a mobile device, they tend to purchase things that are familiar and that they buy regularly—meaning that mobile is probably not the best platform for introducing a new product.

On the other hand, mobile shopping is very effective at building loyalty between a customer and a retailer. It fosters what marketing experts call “stickiness”—the tendency for shoppers to prefer, and keep returning to, brands and retailers that they trust.

For retailers, probably the greatest benefit of mobile technology is the way it builds and strengthens relationships with customers who buy at a low volume. Mobile shopping leads them to buy more frequently—and to place larger orders.

“The more opportunities you give a customer to interact with a retailer, the more the value of the retailer goes up.”

“The impact on the low spenders is much greater than the impact on the high spenders,” Krishnamurthi said. “If you’re a loyal buyer, I have you anyway. But what I’d like to do is convert the low buyers over time into heavier buyers. And [mobile shopping] can create some stickiness, so that you buy more than you used to. And we can build on that. So, over the long run, this can be quite valuable to a retailer.”

Mobile Shopping on the Rise

The widespread adoption of smartphones dates to 2007, when Apple unveiled the iPhone. Google launched the Android operating system the following year. By 2016, an estimated 2 billion people—about one in four people on the planet—will use smartphones. On Thanksgiving Day 2014, 52 percent of browsing and online shopping in the U.S. originated from smartphones and tablets. And these growth trends seem certain to continue. Revenue from mobile commerce will increase from $72 billion in 2013 to an estimated $245 billion by 2017, according to an analysis by the Boston Consulting Group.

Research into the effects of mobile shopping has been limited by the proprietary nature of the information. Companies like Google and Facebook track consumer behavior, of course, but they use it for their own purposes. And since statistics are hard to come by, researchers tend to rely on consumers’ self-reported intentions—not their behavior—in analyzing the effects of mobile shopping.

Wang and her coauthors solved the problem of self-reporting by collaborating with an internet grocery retailer that operates in 12 states and Washington, D.C. The retailer agreed to share its sales data with the researchers. “We’re using empirical data that reflect actual behavior,” Wang said.

They divided the firm’s data into two periods. The first period began in June 2012 and ended in October 2012, when the retailer launched an advertising campaign that encouraged people to use its mobile app. The second period stretched from November 2012 to June 2013.

The researchers compared the behavior of shoppers who used a personal computer in the first period with the behavior of those same shoppers after adopting the mobile app in the second period. (Wang also used a statistical method to create a “control group” of customers who did not adopt the app—but were similar in other ways to those who did adopt it.) How did using the mobile app affect a customer’s ordering habits?

Sticky Fingers

The small screen size is the primary drawback of shopping with a mobile app, since it reduces the amount of information on a page. “In many respects, it’s actually easier to maneuver and learn new material on a PC compared to a mobile device,” Wang said.

But the greatest limitation of mobile technology is also its greatest strength. The portability of smartphones and tablets allows customers to make purchases from anywhere they have an internet connection. And even if they use their devices to make small purchases, the act of regularly engaging with a retailer has a powerful effect on customers’ behavior.

The researchers found that the average order size of low spenders (defined as shoppers whose total spending was less than the median in the first phase) increased after they adopted mobile shopping. They also placed more orders per year than they had using only a computer. Among high-spending mobile shoppers, the size of the order remained about the same. But, as with the low spenders, the frequency of their purchases steadily increased the more they used their mobile devices for shopping.

“The more opportunities you give a customer to interact with a retailer, the more the value of the retailer goes up,” Krishnamurthi said. “And the more the sales revenue from that customer goes up.”

Building Relationships

The upshot is that retailers should think of mobile technology as one way to build strong, durable relationships with customers. But it is best viewed as complement to—not a replacement for—other forms of customer engagement. For example, people are likely to use a computer instead of a mobile app when they buy goods that require more thought and research.

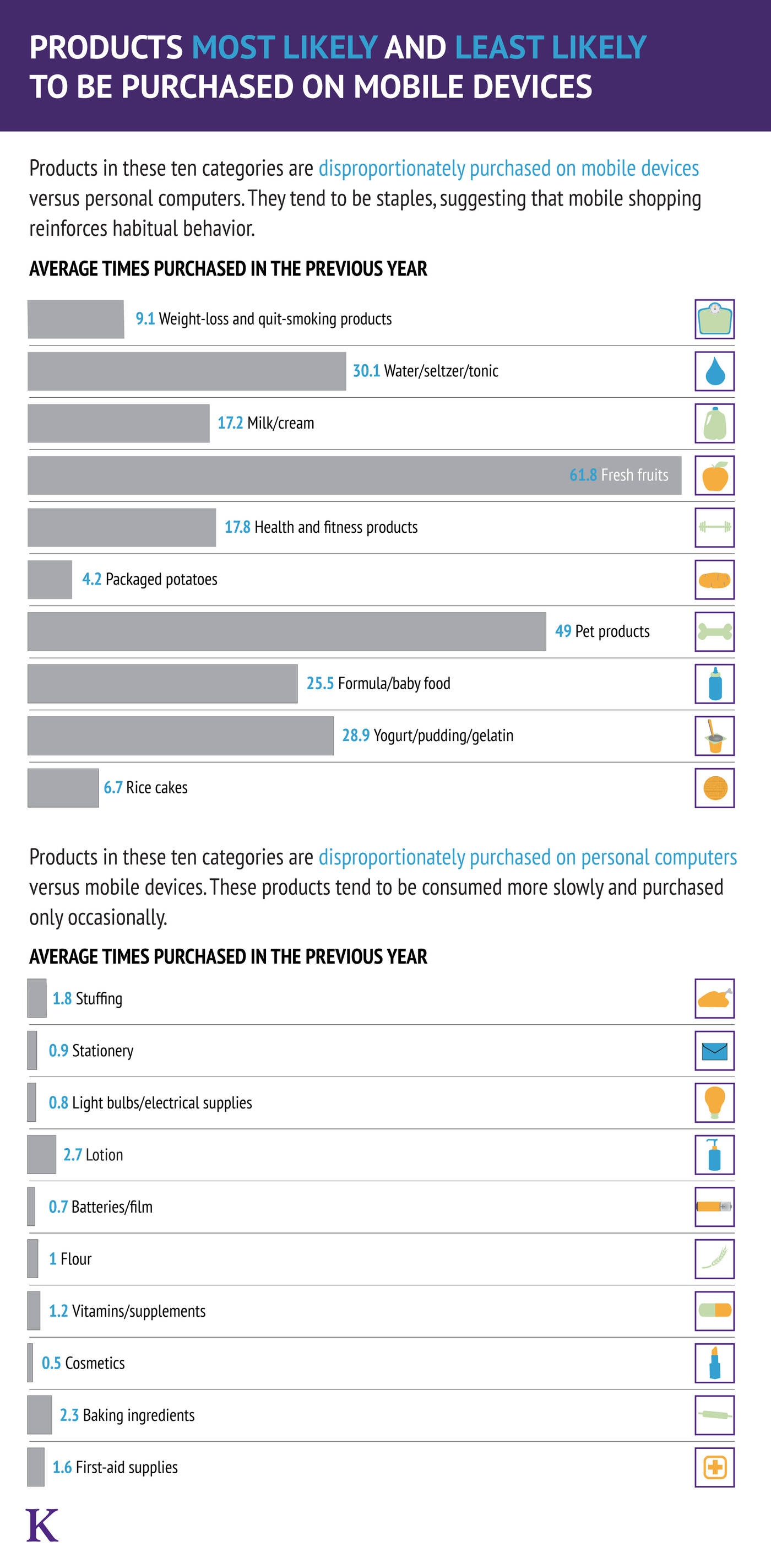

Wang and her coauthors found that the most frequently shopped categories among mobile shoppers were diet aids, beverages, and fruit—the kind of things that people use almost immediately and buy regularly. Among the least frequently shopped categories were stuffing, stationery, light bulbs, and other electrical products—the kind of things that people tend to buy only occasionally.

“If a basket is composed by a lot of PC sessions, it tends to have things that require more consideration,” Wang said. “With mobile sessions, the order is more likely to include things that have a short life cycle.”

The short life cycle means that the customer will likely buy it again soon, and the odds are increasingly good that she will buy it using a mobile device. Retailers that consistently deliver a positive experience to such shoppers will be well positioned to profit from mobile technology’s recent, rapid rise—while building a loyal customer base for the long run.

Wang, Rebecca Jen-Hui, Edward Malthouse, and Lakshman Krishnamurthi. 2015. “On the Go: How Mobile Shopping Affects Customer Purchase Behavior.” Journal of Retailing 91 (2): 217–234.