Marketing Jan 4, 2022

Does Distance Make the Consumer’s Heart Grow Fonder?

New research finds that how far we’re standing from a product changes what we think of it.

Michael Meier

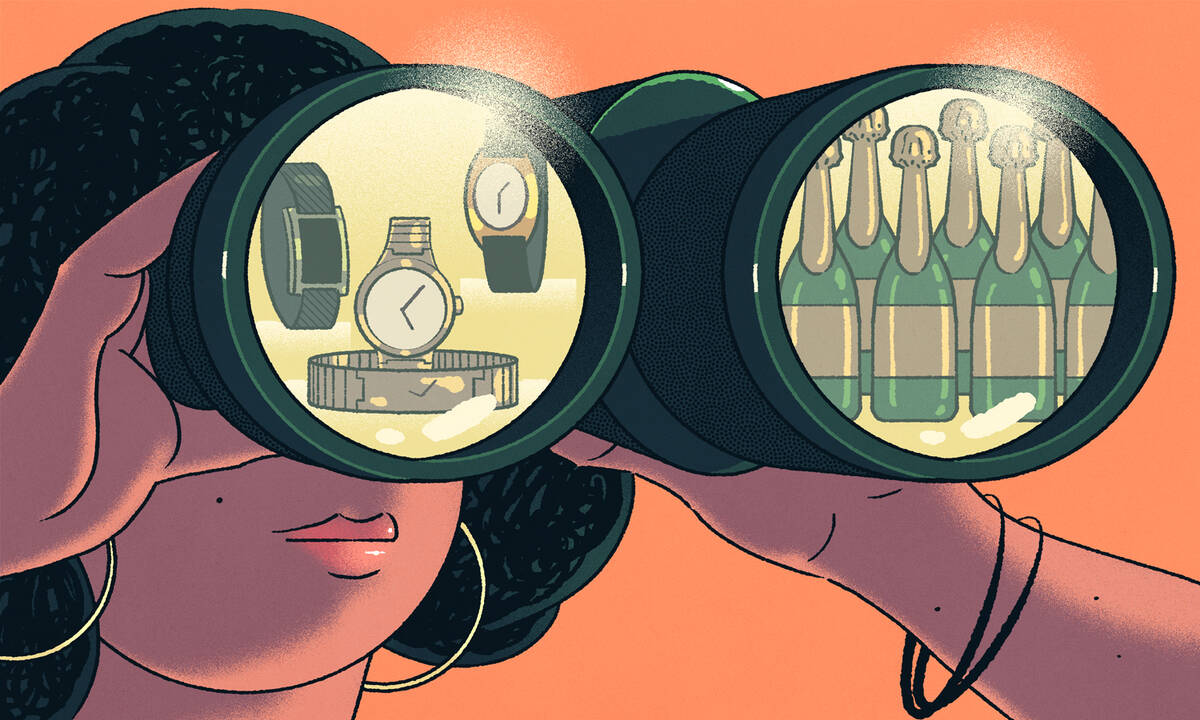

Wander through a department store and you’ll likely see a rich array of product displays: fancy purses on high shelves, watches inside deep glass cabinets, khakis neatly folded on tables, hoodies hanging on easily browsable racks.

These placements are not an accident. Retailers give a lot of thought to where they display products in their stores—and for good reason. Previous research has shown, for instance, that customers respond more favorably to premium brands when their logos are positioned high up above the customer.

But is it distance or height that has this effect on customers? That is, will those premium watches kept deep inside the glass cabinet still benefit from perceptions of prestige even when they are at eye level?

A new paper by Angela Lee, a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School, and coauthors Xing-Yu (Marcos) Chu of Nanjing University and Chun-Tuan Chang of National Sun Yat-sen University, takes a close look at the question.

The authors find that premium brands—those associated with luxury, high price, and prestige—do indeed benefit from distance from the consumer, while popular brands—those associated with accessibility, value, and warmth—are perceived most favorably from up close.

“Effective use of spatial distance is not a one-size-fits-all strategy.”

— Angela Lee

More broadly, the findings reveal that there’s no single, ideal distance between consumers and products: the right distance depends on the image the brand conveys. Designers of window displays, product placements, and ads should take note.

“Effective use of spatial distance is not a one-size-fits-all strategy,” Lee says.

How Brand Image Affects Perceptions of Distance

To investigate how consumers evaluate products at different distances, the researchers devised an experiment involving a print ad for a fictitious brand of chocolate. Study participants (128 students from an executive education program in Taiwan) were told the brand was either premium or popular. Then, they were asked to place an image of a box of chocolates anywhere within a mock ad for the brand, which featured a model near the edge of its frame.

The two brand images yielded different ad designs, the researchers discovered. Participants who believed the chocolate was from a popular brand placed the box nearer to the model than those who believed the chocolate was from a premium brand.

However, the researchers didn’t have a baseline to which they could compare their results, so they weren’t sure whether participants were swayed by the premium brand image, the popular brand image, or both. In their next experiment, they studied the two brand types separately.

In the premium-brand experiment, 179 participants were asked to look at a photo of a handbag and a mannequin and estimate the distance between them. Half of the participants learned the handbag was from a premium brand; for the remaining participants, the handbag brand was described as high quality but not premium.

The researchers used an identical setup for the popular brand experiment, asking 174 participants to estimate the distance between a mannequin and either a popular or unpopular brand of handbag.

Participants believed the premium handbag was farther from the mannequin than the non-premium handbag, and the popular handbag was closer to the mannequin than the unpopular handbag. (In actuality, all four distances were identical.)

To Lee and her coauthors, these results suggested that each brand image had its own distinct relationship to horizontal distance. “Whereas a premium brand image elongated the perceived distance between the product and the model,” they write, “a popular brand image shrank the perceived distance.”

Close and Popular, Far and Luxurious

In another experiment, the researchers looked at the question the other way around, asking participants to infer a product’s brand image while standing at different distances from it.

In the first part of the experiment, 120 participants were randomly assigned to stand either three or five feet from a premium leather backpack. Then, they were asked to rate its prestige, as well as how much they liked it.

Participants who stood five feet from the premium backpack viewed it as more prestigious and liked it more than those who stood three feet from it, the researchers discovered, further reinforcing the association between distance and luxury.

The opposite pattern emerged in the second part of the experiment, which used an identical setup but a slightly different product (a trendy canvas backpack). This time, 80 participants viewed the backpack more favorably overall—and saw it as more popular—when viewing it from a distance of three feet as compared with five feet.

Taken together, these experiments reveal that “the association between image and distance that people have is not just one-way,” says Lee. “When we see something far away, we see it as luxurious. And by the same association, when see something luxurious, we also think it’s farther away. That really shows how ingrained this association is.”

A Real-world Test of Distance and Brand Image

For their final experiment, the researchers wanted to see how the relationship between distance and brand image would play out in a real-world setting. So they partnered with an e-commerce site in China for a field experiment.

They hired a professional web designer to create four versions of an email ad touting a new brand of home fragrance diffuser. “We tried to make it as real as possible,” Lee says.

Half of the ads promoted the diffuser as a premium product with the tagline “Luxurious lifestyle, prestigious choice,” while the other half portrayed it as the popular choice with the tagline “cozy lifestyle, popular choice.” Half of the ads showed the diffuser close to the model, and the other half showed it far from the model. This created four ad types: (1) premium/close; (2) premium/far; (3) popular/close; (4) popular/far.

The email ad included an invitation to claim a $5 coupon for the product. In their analysis, the researchers focused on the percentage of consumers who claimed the coupon, rather than actual sale numbers, which were too small to produce reliable data.

As the researchers expected based on their previous studies, the premium/far ad outperformed the premium/close ad, with three percent of recipients claiming the coupon, as opposed to 1.43 percent. The popular/close ad beat the popular/far ad by a similar margin.

This suggests that the relationship between distance and brand image can have a meaningful impact on consumers in the wild. “This is actual behavior,” says Lee.

Lessons for Ads and Displays

While the experiments don’t show exactly why consumers associate distance with luxury and popularity with proximity, Lee has a few theories.

“We use a lot of physical attributes to describe emotions and abstract concepts,” she notes—think of the phrases “warm relationship” or “distant relative.” Such connections can also flow in the other direction, with physical attributes unconsciously eliciting emotional associations—height, for example, often makes people or products seem more impressive. This close linkage between physical and emotional traits may explain why different products feel better from different distances.

Whatever its origins, the relationship between distance and brand image is one marketers can leverage in ads, window displays, or store designs. By putting more distance between customers and luxury brands, and less distance between customers and brands with mass appeal, marketers can maximize the value of those brands—and likely boost how much customers will pay for them.

The key is knowing what type of brand image you have and making the most of it. Lee adds: “It really has to match the strategy of the brand.”

Susie Allen is a freelance writer in Chicago.

Chu, Xing-Yu (Marcos), Chun-Tuan Chang, Angela Y. Lee. 2021. "Values Created from Far and Near: Influence of Spatial Distance on Brand Evaluation." Journal of Marketing. October 11.