Featured Faculty

Professor of Strategy; Herman Smith Research Professor in Hospital and Health Services Management; Director of Healthcare at Kellogg

Walter J. McNerney Professor of Health Industry Management; Professor of Strategy

Lisa Röper

If you’ve ever passed a building and wondered, “wasn’t that outpatient center just a Barnes & Noble?” you’ve seen a megaprovider.

Megaproviders, according to healthcare economist David Dranove, are large, integrated hospital-based systems. And over time, they’ve become key players in the story of American healthcare.

Episode 1 of our second season of Insight Unpacked charts the rise of megaproviders. It also looks at the role that provider consolidation plays in driving up healthcare costs.

In this first episode, Kellogg Professors David Dranove and Craig Garthwaite, alongside Lawton Burns, tell us about a (literally) big player in the American healthcare industry: megaproviders, which account for the countless hospitals, thousands of physicians, and loads of freestanding outpatient centers that saturate a given region. You probably know them, because their names are emblazoned across all of these structures. But why are they like that? If it’s economies of scale they’re going for, it’s not reflected in the price we pay for healthcare in America.

Listen to all available episodes of season two here.

Resources

“Healthcare at Kellogg: Innovating the Future of Our Healthcare System” on YouTube

The medical interventions we wield today might have been dubbed miracles by our 19th century counterparts. Scientific advances have since afforded us therapies for aggressive cancers, failing organs, and infected wounds, and hospitals are one of the major conduits through which these feats are achieved. It’s important to have that perspective in mind as we critique rising healthcare costs.

To help visualize life before modern medicine, we dug up an old medical illustration that depicts what cholera could accomplish in a matter of hours.

Over time, things improved …

The incredible pace of medical advances made between the turn of the century and the ’60s bolstered demand for healthcare. But because insurance in America was largely employer-based (more on this in episode 3), this left out a lot of people. Lawmakers wanted to change that. So President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Medicare and Medicaid to cover poor, disabled, or elderly Americans.

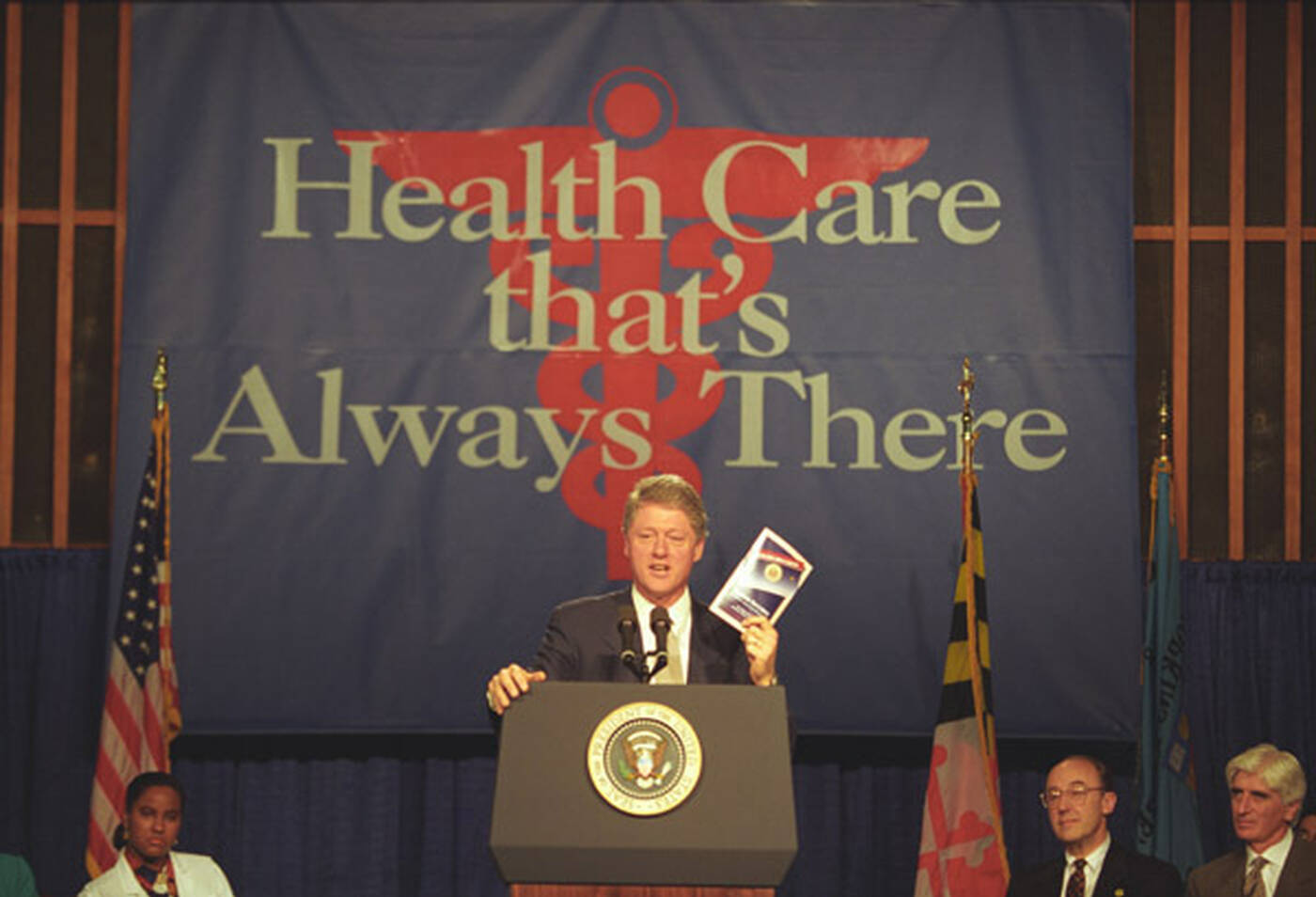

To accommodate the increase in demand from these newly minted patients, the government helped fund hospital expansions. And expand they did. Dranove and his Big Med coauthor Robert Lawton Burns say that the subsequent decades saw healthcare spending climb higher, inspiring the creation of Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) and Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs). HMOs and PPOs were contracts that helped insurance companies negotiate more favorable rates with providers. In response, providers bulked up and started merging with one another to become more formidable negotiators. Healthcare costs continued their ascent, and in the ’90s, President Bill Clinton proposed universal healthcare as a way to curb that.

The prospect leads to another wave of consolidation among providers, until eventually they morph into the colossal systems we’re familiar with today.

To read about this history in more detail, as well as how it has driven up costs, check out our interview with Big Med coauthors Dranove and Burns in Kellogg Insight.

You can also read an excerpt of Big Med here.

Big Med is available for purchase here.

You can find additional sources for this episode hyperlinked in the podcast transcript below.

Laura PAVIN: Once upon a time—if you can believe it—health insurance in the U.S. used to be really cheap.

Craig GARTHWAITE: The first health-insurance plan was actually pretty cheap. I think it was like 50 cents a month, and you got something like three weeks of insurance coverage to the hospital. And so that was the original version of health insurance that we had coming out of the depression.

PAVIN: This was America’s very first health-insurance plan, in 1929. It was between a group of teachers and a local hospital. If you adjust for inflation, that 50 cents would be $11 today. Which, could you imagine?

Of course, things were cheaper back in the day for a reason.

GARTHWAITE: Before you start thinking that was a really good bargain, back then, I think you were better off avoiding the hospital than you were going to it. So I don’t think they were still using leeches. I think they had some degree of anesthetic or something like that, but it’s not really where you wanted to get healthcare. And so it might’ve been 50 cents and be perfectly priced at 50 cents.

PAVIN: That’s Craig Garthwaite. He’s a professor of strategy at Kellogg, director of the Healthcare at Kellogg program, and an expert on the business of healthcare.

And, up until the late 1800s, hospitals were where you went to die or be in a tremendous amount of pain. They were basically holding pens for people with diseases who couldn’t afford to be treated at home. Patients were sometimes called “inmates.” And if you needed surgery, best of luck to you, because if the scalpel didn’t kill you, the hospital infection probably would.

There’s a medical drama on HBO Max called The Knick that depicts this era pretty well.

[the Knick clip]

BOSS: Ain’t you supposed to wash your hands first?

DOCTOR: Are you telling me how to do my job? I’ve been practicing medicine since the war. And in all that time, I can tell you, I never had a single complaint from anyone that lived.

LACKEY: For the love of Christ, boss, why don’t we take him to the Knick?!

[end of The Knick clip]

PAVIN: Obviously, things improved. Now, hospitals put cancers in remission. Transplant organs. Repair your heart. Keep premature babies alive. It’s crazy to think how they went from the place where you went to die to the place you went to heal.

[ABC News clip 1]

NEWSCASTER: Sharp Mary Birch Hospital today announced the birth of the world’s smallest surviving baby. She was born in December weighing just 8 oz and was sent home this month weighing 5 lbs.

[end of ABC News clip 1]

[ABC News clip 2]

NEWSCASTER: This is the moment so many people are talking about. Grayson Clamp, three years old, had never heard his father before.

DAD: Daddy loves you. Daddy loves you.

NEWSCASTER: Grayson points his finger there, hearing sound for the first time ever.

[end of ABC News clip 2]

PAVIN: This is actually where our story begins. Because when hospitals started making people better, it created a demand, from everyone, to be better; to live longer and healthier lives. But, in America, putting a price on “better” has gotten really complicated.

[NBC5 News clip]

NEWSCASTER: Jamie Rudder injured her hand and says the Chicago Fire ambulance drove her less than two miles to the hospital.

Jamie RUDDER: Not even 10 minutes.

NEWSCASTER: Rudder says the crew helped stop the bleeding, but her bill for the ambulance ride? $755.

[NBC5 News clip fades]

[CNBC clip]

Ashley PALMISCINO: They billed our insurance company over $3 million for the cost of transplant. And I have another EOB right after it, which was another $1 million. So, you’re looking at a $4 million transplant. I don’t know what people do without insurance. How could you even begin to pay that?

[end of CNBC clip]

PAVIN: You’re listening to season 2 of Insight Unpacked: “American Healthcare and Its Web of Misaligned Incentives.” I’m Laura Pavin. This season, we’re tackling the big, hairy mess that is our American healthcare system. The United States spent about four-and-a-half trillion dollars on healthcare in 2022. That’s more than any other country.

But here’s the kicker: in spite of all this spending we’re doing, it’s not entirely clear how much healthier we’re getting compared to other rich countries. Life expectancy at birth in the U.S. is lower than it is in other big, wealthy countries like France, Germany, and Japan. The average American doesn’t seem to be getting a ton of bang for their buck.

But how is that even possible?

If you ask an economist, they’ll blame market incentives. And we did ask an economist. Well, we asked several. And they say what we have in American healthcare is a tangled mess of misaligned incentives that don’t always benefit the patient.

What are those, you ask? Well, in this five-part edition of Unpacked, we turn the lens on some of the biggest players in the industry.

We look at hospital systems …

Robert Lawton BURNS: They smelled the money.

PAVIN: Doctors …

David DRANOVE: Physicians, when they make a medical decision, have some consequences.

PAVIN: Health-insurance companies …

GARTHWAITE: Are we willing to make investments today that pay off 20 years from now? Alright? I think most of us fail on that sort of proverbial marshmallow test in one way or the other.

PAVIN: And pharmaceuticals …

Amanda STARC: The problem is that these drugs are kind of expensive for a reason.

PAVIN: Eventually, we’ll even turn the lens on ourselves.

PAVIN [clip]: Wow! Now, I feel really bad getting my allergy shots at this outpatient center in, like, Glenview.

GARTHWAITE: There’s a choice there.

PAVIN: Throughout the series, you’ll see how money shapes decisions by every single major player in this story. It’s no wonder we haven’t been able to control spending so far. Of course, this brings us right to our final question—and perhaps the biggest question of all—which is, is it even possible to create a system that gets us more for all this money we’re spending? And, should that system be Universal Healthcare? Or, could the answer be sitting right under all of our noses, Somewhere within the current U.S. Healthcare system? Don’t worry, we’ll get into that.

But today, in this first episode, we look at how hospital systems became so massively massive and, of course, very lucrative. Every step of their journey to this point was paved with the push to grow—first explicitly, and then implicitly. But bigger hasn’t always meant better.

That’s next.

…

PAVIN: Every week, I drive about 25 minutes to an outpatient center on the North Shore. It’s a glistening four-story building with a giant parking lot, well-manicured landscaping, and a pretty good menu of services and specialties. I go there for allergy shots. And from the moment I step foot in this clinic, I’m on a well-oiled assembly line that pushes me out the door in less than an hour. It’s well-staffed. It’s well-resourced. It’s a megaprovider.

DRANOVE: To some extent, as a consumer, we know them when we see them.

PAVIN: That’s David Dranove. He’s another economist at Kellogg who studies the healthcare industry. He wrote a book about megaproviders called Big Med: Megaproviders and the High Cost of Health Care in America.

And here’s how he says you can spot them.

DRANOVE: They’re advertised. Their names are emblazoned up, not just across hospitals, but across lots of buildings. A lot of them are former Borders and Barnes & Nobles buildings. And they take over existing structures all throughout the city and suburbs.

PAVIN: The anatomy of a megaprovider is a whole bunch of hospitals, thousands of physicians, and a lot of freestanding outpatient centers, like the one I go to for my shots.

Just about every metropolitan area has its own. Or multiple! You might have even seen their TV commercials.

[Advocate commercial]

NARRATOR: Today, Advocate Aurora Health and Atrium Health join forces to reimagine care and advance health equity for all.

[UPMC commercial]

NARRATOR: We are uncommon to the core. We are UPMC.

PAVIN: Northern Illinois has Advocate Health. Western Pennsylvania has UPMC. Northeast Ohio has Cleveland Clinic. And the list goes on. All of them have the kinds of revenues you see giants like Spotify, Gucci, and Tesla pulling. The most recent numbers I could find put UPMC’s revenues at $26 billion. And many of them are still growing, too, slowly getting a toehold in new cities and states.

To really know if you have a megaprovider on your hands, though, you need only to take a look at its relationship with insurance providers.

DRANOVE: So as a practical matter, if a provider is a megaprovider, then when they negotiate with an insurance company, they know they’ve got the upper hand. That insurance company has to include that megaprovider in the network, or it’s going to have a very difficult time selling its product to employers.

PAVIN: That’s right: if you’ve got a hospital system that’s so big and powerful in the region that few will even bother with insurance plans that don’t include it, you’ve got a megaprovider.

Of course, size, profits, and power doesn’t make a company nefarious. But what megaproviders have done, Dranove says, is pummel the competition. They swing their weight around to raise prices without necessarily offering anything new or better in return.

But how did we, as a country, get to this place with megaproviders? Here is where I need some help, Jess.

Jessica LOVE: Okay. Hello there.

PAVIN: Audience, this is Jess Love. She’s editor in chief of Kellogg Insight. And Jess is going to be co-hosting this season with me. She and I both talked to Dranove and his Big Med coauthor Lawton Robert Burns. Burns teaches healthcare management at UPenn’s Wharton School.

And so, Jess is going to help me tell this story.

LOVE: Yes. Should I start?

PAVIN: Go right ahead.

LOVE: Okay! So Dranove and Burns say there were a few big turning points that helped megaproviders become what they are. Our story starts in the 60s. I’ll let Dranove set the scene.

[old-timey music]

DRANOVE: A physician in the 1960s was usually a solo practitioner in a small group, and they were on a pedestal. They were the most respected people in their community, in the eyes of their patients. They could do no wrong. They were, in the words of Victor Fuchs, “the captain of the team.” They controlled the healthcare system, and everybody else in the healthcare system agreed with everything they said.

LOVE: These were heady times for hospitals and doctors. No one was really keeping a lid on what they could charge or questioning their care decisions. They essentially got a blank check from insurance companies and the government to do what they wanted. And patients were happy because they were getting treatments for things that historically were a death sentence.

PAVIN: And I think we should say that this was the case for some patients but definitely not for all. Tons of people weren’t insured. Namely, the elderly and the poor. But politicians wanted to change that. They wanted to create some form of government-backed insurance. And then, in 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signs Medicare and Medicaid into law.

[clip]

President Lyndon B. JOHNSON: No longer will older Americans be denied the healing miracle of modern medicine. No longer will illness crush and destroy the savings that they have so carefully put away over a lifetime so that they may enjoy dignity in their later years. No longer…

[clip fades]

PAVIN: So, Johnson signs this thing, and suddenly, a ton more people have insurance. Which is pretty transformative, but there’s one problem.

LOVE: Big time. So there was all this pent-up demand from people who were poor, or elderly, or both. They didn’t have insurance before. Suddenly, now they have insurance. And they’re ready to get care. The problem is: there aren’t providers to handle this sudden surge in demand. So, providers had to build up supply. Quickly. And the government was like, “You know what? We can help you with that.” And they dangle a bunch of money in front of them to help them expand. And the for-profit hospitals are the first to spring for it. Here’s Burns.

BURNS: They smelled the money. And so they built up these hospital systems and bought new plant equipment, bought up independent hospitals, refurbished them, ‘cause they got reimbursed for all that refurbishment. And so the federal government just financed and incentivized the formation of for-profit hospital systems in the sixties, and that motivated the nonprofit hospitals to follow suit subsequently.

PAVIN: And so it’s started: the incentive for providers to grow. But they couldn’t do it alone.

DRANOVE: They liked the idea of having more patients, but they didn’t know how to deal with the regulations. And so you saw for the first time outside organizations coming in and saying, “We can help.”

PAVIN: The management class enters the picture in a big way: to help hospitals and doctors figure out the legal nuances of this new payer—the government. That helps providers focus on treating this ballooning list of patients, which helps them grow. And things are really humming along.

And at this point, I want to pause and point out that the healthcare system’s incentives, and the government’s incentives, and the patient’s incentives, they’re all pretty much aligned: get bigger and care for all the new people who now have insurance.

LOVE: But …

PAVIN: There’s always a “but.”

LOVE: But, starting in the 70s and 80s, something happens that pushes providers to grow even bigger.

Up to this point, health spending has exploded because more people are getting care, and there’s big demand for all these medical breakthroughs that are happening. In 1963, we got our first measles vaccine. Nineteen sixty-seven marks the first year that no American dies from rabies. That same year, the first human-to-human heart transplant is performed.

[SABC News clip]

NEWSCASTER: In five drama-filled hours, the heart of miss Denise Darvall, who was tragically killed in an accident, was transferred to the body of mister Louis Washkansky, a 53-year-old businessman suffering from an incurable heart disease.

[SABC News clip fades]

LOVE: People with conditions once thought untreatable are able to get treated. So they do.

And, as this is happening, the employers that are sponsoring health insurance for their employees kinda start noticing how much they’re spending. And they’re like, “What do we do? We need some help reining costs in.”

PAVIN: They end up turning to the insurance companies to help negotiate prices down with providers. And insurance uses a few different tools to do that. Two big ones? Health Maintenance Organizations and Preferred Provider Organizations. HMOs and PPOs. We’ll discuss these in more detail later in the season. But, in a nutshell, they’re contracts between the insurance companies and the providers that end up putting insurance companies in the power position. They had more of a say in what they paid providers for their services. And if providers didn’t agree? Well, they’d get less business because these insurance companies were merging and getting bigger and covering a lot more patients. So insurers could be like, “Don’t want our money? Good luck finding patients that carry different insurance.”

LOVE: Right. And the providers? They get a bit resentful. Here’s Burns again.

BURNS: That puts pressure on the financial flows going to the hospitals and the doctors. And they now realize, “hey, you know, we have a common enemy; it’s the insurance companies.” And so they get this brilliant idea, and it came from a number of places, “let’s join forces, and we’ll control more of the market, and maybe we can have some more bargaining power.”

LOVE: Providers try to level the playing field. And you see this really big merger wave happening among physician practices and hospitals to give them more power at the negotiation table. And it works! So, spending really goes unabated.

PAVIN: Alright, so now we can see a little more clearly the dance we’re starting to do here. Healthcare spending goes up, there’s an effort to control that spending, and a response to make sure that we keep spending. And size, for providers, is an effective way to do that.

LOVE: That’s right. Which brings us to our next turning point. It’s 1993 and President Bill Clinton hits the stage.

[clip]

Bill CLINTON: Despite the dedication of literally millions of talented healthcare professionals, our healthcare is too uncertain and too expensive, too bureaucratic and too wasteful. It has too much fraud and too much greed. At long last, after decades of false starts, we must make this our most urgent priority, giving every American health security; healthcare that can never be taken away; healthcare that is always there. That is what we must do tonight. [Applause.]

[clip fades]

LOVE: Yes, that’s Clinton proposing universal healthcare to Congress. He even holds up a mock universal healthcare card to show everyone what it would look like. It was one part of a bigger healthcare bill he proposed to reform the system.

Dranove says the Clinton plan would have brought us something that might sound kind of familiar to you.

DRANOVE: So to understand the Clinton system, think of today’s health-insurance exchanges, except instead of health-insurance companies, instead of you as a consumer choosing amongst several health-insurance companies on the exchange, you would choose amongst several integrated health systems on an exchange. So the providers were scrambling to create systems so they would be able to participate.

PAVIN: Picture the current healthcare.gov marketplace, only instead of insurance plans from Blue Cross Blue Shield or United Healthcare, you’d be choosing from a list of different health systems where you’d get your care. Like Sutter, Advocate, or Intermountain.

Obviously, this thing didn’t pass, but all the talk about it got providers acting as though it would. They bulked up, called themselves Integrated Delivery Networks, gobbled up primary-care and specialty-physician practices, outpatient surgery centers and diagnostic facilities, home health services and long-term care facilities. They infiltrated every nook and cranny of their communities. Some even offered health insurance.

By the late 90s, we have something that looks a lot like what we have today. These catch-all places where we can go for every medical need imaginable. Need an allergy shot? Drive to our facility here! Need bloodwork done? Hang a right to our phlebotomist.

LOVE: Let’s pause again to notice that this saga with the Clinton plan and hospital systems, it’s another example of that thing happening. Someone tries to come in and control the cost of care, and it creates this reaction from providers to keep things where they’re at. It’s actually a little comical, because this time the government just talked about reforming things. And that was enough to trigger a response from hospitals.

PAVIN: Yeah, and of course healthcare spending goes up during all of this. And if you’re wondering, “where were the antitrust regulators?” Well, they were kind of caught flat-footed. When they did try to intervene, they didn’t have the right tool kit.

DRANOVE: They initially, in the courtroom, used a methodology that had been applied to coal.

LOVE: Coal. The Federal Trade Commission was taking a page out of the same book they used to assess competition in the coal industry. Basically, instead of looking at how coal flowed through a market, they looked at the travel patterns of patients in a market. Long story short, it wasn’t the best mechanism and antitrust agencies lost a lot of merger challenges with it.

Now, Dranove later came up with a more reliable method that federal regulators could use, called Willingness-to-pay. But unfortunately, it was too late. Lots of mergers had already happened. And it’s really hard to undo mergers that have already happened, so we’re kind of stuck. We remain a nation of megaproviders.

PAVIN: In all of this, the thing that was pushing growth at every turn seems to be this idea that bigger was better. The point we’ve been making this episode is that bigger is better at the negotiation table. It affords you market power, so you can hold onto those healthcare dollars. But I also think we need to be fair and say that some, or maybe even a lot, of the growth happened because executives thought that they could achieve economies of scale. Like, how Walmart uses its size to buy in bulk and gives their customers discounted prices.

But that really hasn’t panned out. Healthcare isn’t Walmart. It’s a very different beast.

Like, say you have two hospitals with neonatology units. And they merge, and now they have a common owner. On the one hand, if you look at it from a basic economics standpoint, you should be able to combine the two and find some kind of efficiency. Not so, say Dranove and Burns.

DRANOVE: But that now requires a lot of things, convincing patients that they should have their baby somewhere else and convincing the doctors that they should move their practices somewhere else. And neither of those things happened, and you name your specialty and the specialty organizations objected at every turn.

BURNS: Yeah, uh, not only do you have to get the doctors to move from there to there, but you have to convince the head of neonatology here to give up his or her position.

DRANOVE: Oh yes, that’s right [chuckles].

BURNS: [chuckles] … and be subsumed under somebody else. And the professional rivalries here are amazing.

PAVIN: The incentives for doctors and systems are just very at odds.

Dranove and Burns say that the result is a bunch of mammoth healthcare providers with a ton of power in their local markets, because patients come to rely on their doctors and state-of-the-art facilities, and that puts the pressure on insurance to sort of bend to the will of providers via their patients.

Unfortunately, the kind of match that lit the fuse here started out with good intentions: “Use these federal dollars to expand to care for all these new people with health insurance.” But it ended up creating this monster where, if you want to survive in the business of providing healthcare, bigger is better.

LOVE: Now. It might seem like we’re picking a lot on hospitals here. So it is important to clarify a few things. First, it’s not the case that, if all the megaproviders were to suddenly disband, it would instantly lower the cost of healthcare for patients. Garthwaite is adamant about this. For reasons we’ll get into later in the series, he says insurance companies also contribute to rising costs.

GARTHWAITE: Really big insurers are not here for your benefit. They’re here for their shareholders’ benefit.

LOVE: It’s also worth pointing out that not playing by the “bigger is better” playbook can have some serious consequences. Because a lot of hospitals are not doing so well right now. Maybe you have heard the term “healthcare desert?” The past few years have seen a number of hospital bankruptcies, particularly as pandemic-related federal funding has decreased. And those taking the brunt of the hit are smaller, independent hospitals in rural areas that struggle to negotiate higher reimbursement rates. They can’t compete with bigger systems that can pay more for labor.

PAVIN: And there’s a final caveat we want to make. It’s that a lot of megaproviders are really good. Like, if you look at any list of the top hospitals in the nation, in terms of the care they are able to provide to patients, you’ll see a lot of megaproviders. Northwestern Memorial Hospital, which is affiliated with Northwestern University’s medical school, is the top-ranked hospital in the state of Illinois, and it is a megaprovider!

LOVE: And this is actually part of the reason why these hospital systems are so effective at the negotiating table. Here’s Garthwaite again.

GARTHWAITE: It’s not that they are able to demand the status that they get with the insurers just because they’re big. They’re not a must-have, like have-to-be-in-the-insurance-network, providers simply because they’re large. It’s because people really want to go there.

LOVE: That’s right. Most patients want the best care possible. Heck, most doctors want to provide the best care possible. And in many cases, the best care is found at a megaprovider. Not because it’s big, but because over the years, for all the reasons we discussed, university-affiliated hospitals and other places where you can access the very best in cutting-edge medicine got big.

LOVE: I’ll be the first to admit it: I go to megaproviders for everything, and I have been really happy with my treatment.

PAVIN: Me too. I literally just got an allergy shot there this morning. I actually got a hug from a nurse I haven’t seen in a while, and I left smiling.

[music]

LOVE: So, megaproviders have their drawbacks and benefits. What does that mean for a plan to get more bang for our healthcare bucks? Well, the American healthcare system is full of actors. Megaproviders are a big one. A very big one. But they aren’t the only actor we need to take a critical look at. Doctors, themselves, are another place to look.

PAVIN: Yeah. Which is kind of surprising because we usually think of doctors as more of the victims in all this.

LOVE: Our experts say, “that’s probably too simple.”

LOVE: Next time on Insight Unpacked, doctors are stretched so thin that they can barely spend even 10 minutes with patients. And yet, doctors are the group that our experts say are responsible for the biggest chunk of our healthcare spending. What’s happening in those 10-to-15 minutes with their patients? Or, rather, what’s happening outside of those 10-to-15 minutes they’re spending with patients?

PALOMO: There’s always a pressure, like, “Okay, I have a 15-minute slot. How do I turn this into a level four so that I can maximize the revenue generation.”

LOVE: That’s on episode two of Insight Unpacked, coming out next week.

PAVIN: We’ll see you then.

***

CREDITS

PAVIN: While you’re waiting for our next episode, you can check out links, supplementary materials, and images for this episode at kell.gg/unpacked.

This episode of Insight Unpacked was written by Laura Pavin, edited by Jess Love, and produced by the Kellogg Insight team, which includes Fred Schmalz, Abraham Kim, Maja Kos, and Blake Goble. It was mixed by Andrew Meriwether. Special thanks to Craig Garthwaite, David Dranove, and Robert Lawton Burns. As a reminder, you can find us on iTunes, Spotify, or our website. If you like this show, please leave us a review or rating. That helps new listeners find us.