Featured Faculty

Professor of Strategy; Herman Smith Research Professor in Hospital and Health Services Management; Director of Healthcare at Kellogg

Professor of Strategy; Associate Director of Healthcare at Kellogg

Lisa Röper

In 2022, Congress granted Medicare a privilege traditionally reserved for private insurers: the ability to negotiate directly with drugmakers. It’s expected to save American taxpayers tens of billions of dollars, but Kellogg economists warn the savings come at the expense of future innovation.

Understanding why requires understanding how new drugs come to market in the first place—and the incentives that make the whole system go.

Episode 4 of our second season of Insight Unpacked explores the role of pharmaceutical companies in driving up healthcare spending. It also considers what’s at stake if we pay lower drug prices at the pharmacy. We produced this episode with help from Kellogg faculty members Amanda Starc and Craig Garthwaite, as well as Boston University School of Law’s Kevin Outterson.

Listen to all available episodes of season two here.

Resources

“Healthcare at Kellogg: Innovating the Future of Our Healthcare System” on YouTube

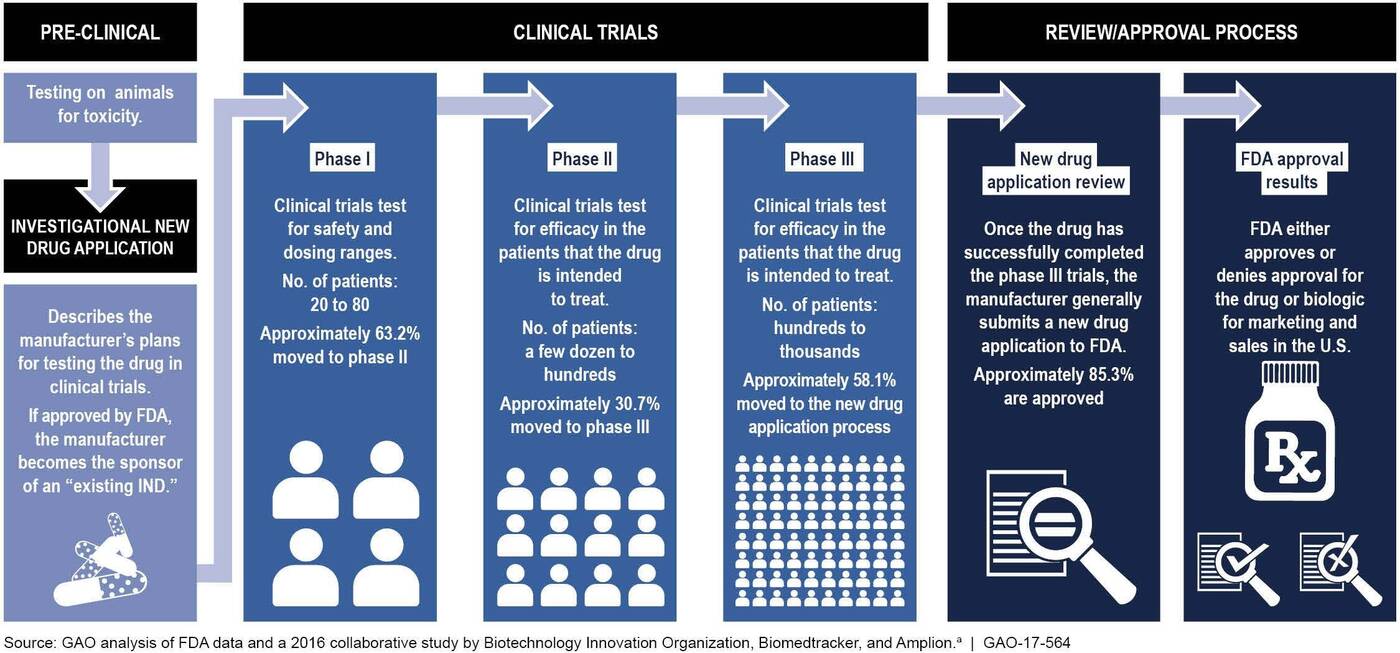

Before hitting the market, new drugs undergo extensive lab tests and clinical trials, followed by a stringent regulatory review and approval process. The process can last between 10 and 15 years and cost upwards of $1 billion. And it often yields failure. Estimates suggest that about 10 percent—maybe as much as 14 percent—are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

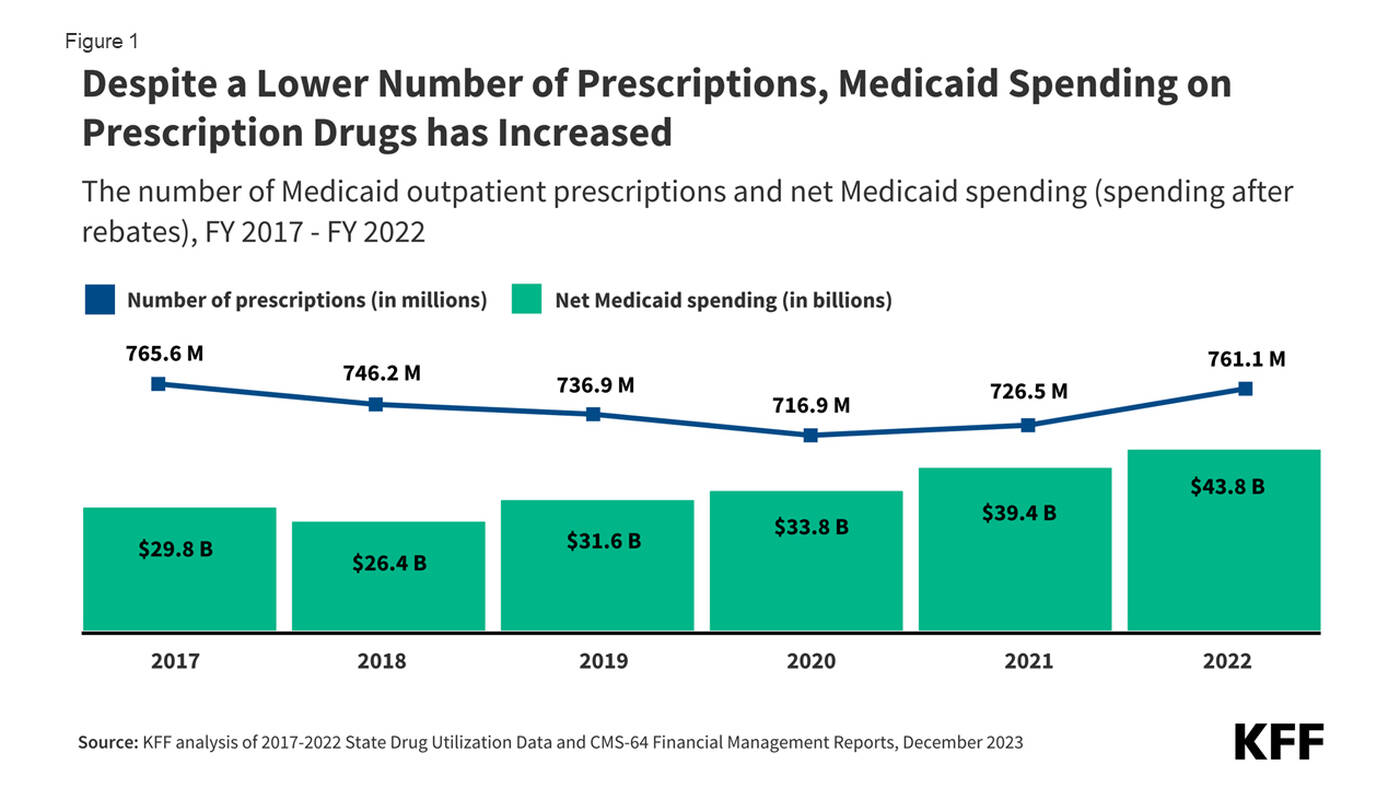

What makes this risk worth taking? The promise of a payday. Payments from Medicare, which is the largest single payer for drugs in America (and until recently did not negotiate on drug prices), currently fund a lot of drug innovation, here in the U.S. and around the world. Absent this, innovation is going to look less profitable for firms. Our experts say this means we will likely see drug development slow as a result. (On March 22, Craig Garthwaite testified before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, making a similar point about the importance of generously rewarding innovation with respect to the Moderna Covid vaccine. You can read his testimony here (PDF).)

To see how much the promise of a payday drives drugmakers, we consider what happens when there is no big payday. Such is the case for new antibiotics, which are supposed to be taken sparingly to slow the pace of antibiotic resistance. The result? A shortage of new antibiotics being developed.

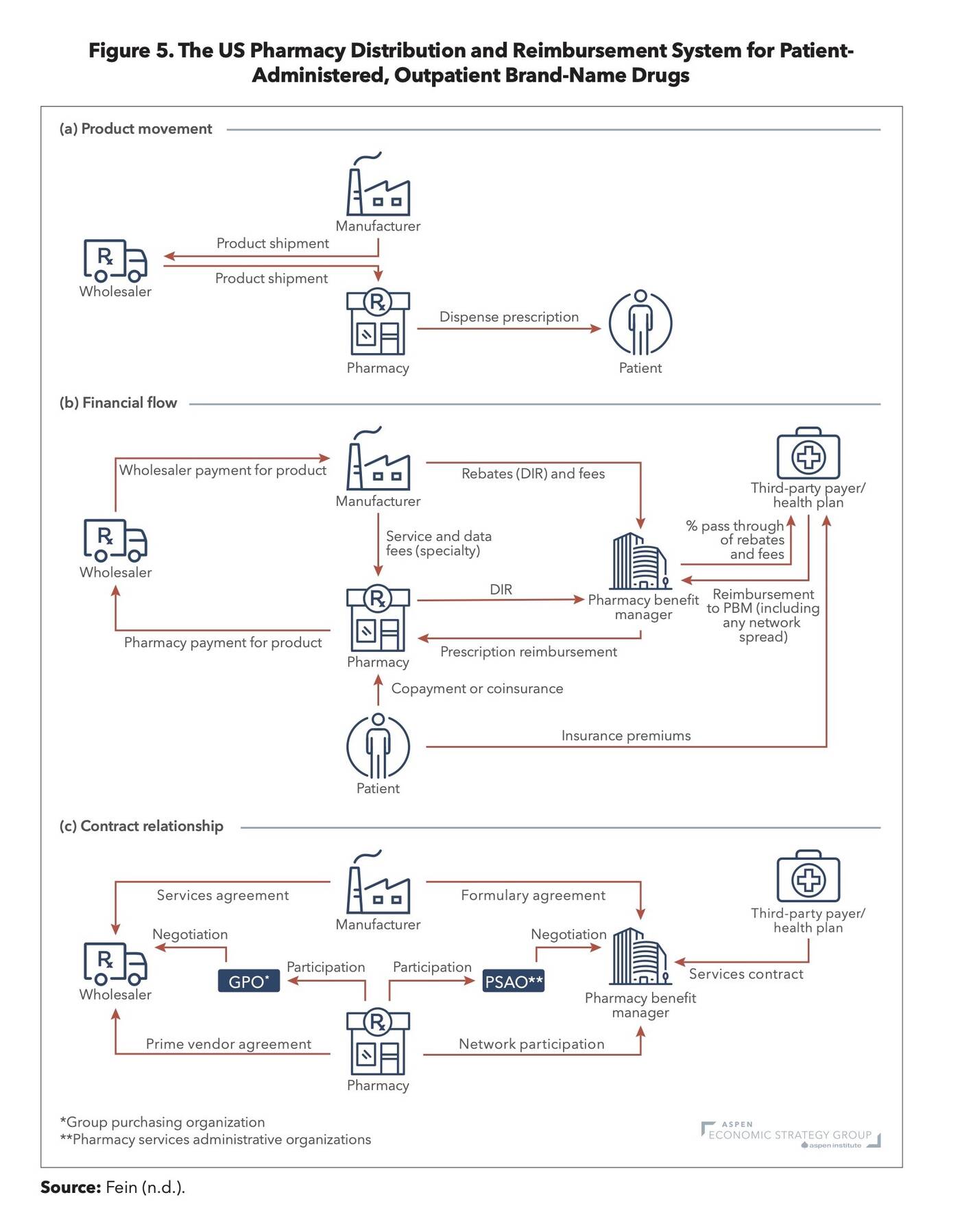

Kellogg economists Craig Garthwaite and Amanda Starc have recommendations to improve the value we get for our money. Overall, they want to see more competition and transparency up and down the drug value chain—which, we might add, is incredibly complex.

Starc and Garthwaite recently put together a “Primer and Policy Guide,” where they describe their policy recommendations in more detail. Kellogg Insight has also featured their insights on the topic in an article called, “Can We Build a Better Prescription Drug Market?”

One of their suggested reforms takes aim at Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs. PBMs negotiate drug prices with manufacturers on behalf of their clients, insurance plans. But because their contracts with drug manufacturers and insurance plans are confidential, there’s confusion over who really benefits from these negotiations. The New York Times recently reported on PBMs, finding many cases that call into question how much cost savings PBMs really provide their clients.

Finally, last year Amanda Starc answered Kellogg Insight audience questions about drug policy as part of our The Insightful Leader webinar series. Wondering why it costs you thousands out of pocket for chemo infusions that can be made in a lab for $2.00? Or perhaps you’re curious why we might be paying too little for some generics?

You can find additional sources for this episode hyperlinked in the podcast transcript below.

Podcast Transcript

Laura PAVIN: Hey there. It’s Laura Pavin.

Jessica LOVE: And Jess Love.

PAVIN: Last summer, President Joe Biden made a big announcement about something Medicare was doing. It was going to negotiate down the cost of 10 different drugs.

President Joe BIDEN: Drugs that treat everything from heart failure, blood clots, diabetes, kidney disease, arthritis, blood cancers, Crohn’s disease—and so much more—reducing the cost of these 10 additional drugs alone, will help more than nine million Americans.

LOVE: Many of you listening might already be familiar with this story, but bear with us for a second; there’s more to it.

So, Medicare previously could not negotiate directly with drug manufacturers to get lower prices, while private insurance companies could do this. Seems kind of unfair, right?

PAVIN: Congress thought so too. So, in 2022, they said, go forth, Medicare. Go forth and negotiate! And that’s what it’s starting to do now, with these ten drugs. Jardiance, Januvia, Entresto, Imbruvica—maybe you’ve heard of them, maybe you take them, but these are some of the drugs that Medicare can now haggle over.

Amanda Starc is a healthcare economist at Kellogg. And she fully expects Medicare to get its way in these negotiations.

Amanda STARC: So the old joke is that the United States government is an insurance company with an army because the government is such a large insurer. If it wanted to, it could almost certainly negotiate lower prices.

PAVIN: And it will. It’s going to be great for the people who take the drugs. And it’s going to save American taxpayers tens of billions of dollars—since we foot the bill for Medicare.

LOVE: Yeah. So, what Medicare is doing now is a good thing. Right?

Starc doesn’t share this optimism. She says we’re paying a price we can’t see yet.

STARC: The problem is that these drugs are kind of expensive for a reason.

LOVE: You’re listening to Insight Unpacked. This episode, we look at the spiraling costs of prescription drugs. About 1 in 4 Americans say it’s hard to afford the cost of their prescriptions. But the buck doesn’t stop with patients; as we just mentioned, the costs fall on taxpayers and the private businesses that insure their employees, too. So, you’d think that pharmaceuticals is one place where reforms can quickly make a huge difference in helping us get more value for our healthcare dollars.

PAVIN: But according to Starc, reforms that seem like they make a lot of sense today could send our healthcare system in a direction we don’t want. And that’s because what it takes to actually get a drug on the American market might actually make the sky-high prices we pay for them somewhat reasonable? Or at least better than the alternative.

We talk about all of it, next.

* * *

LOVE: Okay, so the government is going to directly negotiate the price of certain drugs that millions of older Americans take. And make no mistake, the government will get those lower prices, says Starc. Here’s why.

The U.S. government insures almost one-fifth of the U.S. population, through Medicare.

So, with one-fifth of the population in tow, Medicare has a lot of negotiating power. Drug companies need access to these Medicare patients, so they’re going to give the government those lower prices it wants. And in the short term, this is great news! Starc again.

STARC: And so if you’re thinking about only the drugs available today, then you’re better off.

LOVE: This is going to knock down the price of these drugs.

But Starc says this strategy from the government isn’t really playing the long game.

STARC: We have to think about the investments that manufacturers are going to make in bringing new drugs to market if they know that the government is going to bring that army and say, you have to give us a lower price.

LOVE: Because Medicare patients are such a huge market for big pharma, Starc says that giving the government a discount on this kind of scale is going to make drug innovation not as attractive to the pharmaceutical industry. So much less attractive that we might see less of it.

Because developing drugs is incredibly expensive.

PAVIN: Here is where I think we need to know a little bit more about what actually goes into the process of developing a new drug.

Kevin OUTTERSON: How are you?

PAVIN: Good how are you?

PAVIN: We talked to Kevin Outterson. He’s a law professor at Boston University, but he’s also the executive director of CARB-X. It’s a nonprofit that supports the development of antibiotics.

And Outterson says that coming up with new antibiotics that can target different bacterial strains? It’s a painstaking process.

He says that people often don’t seem to appreciate what’s involved in the process of developing new drugs, or even just understand it at a basic level. And certainly the media doesn’t help here.

OUTTERSON: Every once in a while, a couple times a year, there’ll be a story in science or nature, and it’ll be picked up by the press: “Oh, somebody has discovered a new antibiotic in the woods of Maine or in a deep ocean thing or whatnot, and amazing new antibiotics is going to save all these lives.”

[Outterson fades out under The Washington Post]

The Washington Post video narrator: Can this dirt be potentially life-saving? Researchers at the Rockefeller University in New York City have found that bacteria extracted from local parks contain genes that might encode drug-like molecules, like antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and cancer-curing agents.

[The Washington Post fades out under Outterson]

Kevin OUTTERSON: It’s really an idea with some data, and they don’t have a hit yet. They don’t have a lead molecule yet. They’re still working on it, and they’re years away from that. And from that moment in which there’s a press report of new antibiotic until the moment in which they might get FDA approved, it is at least 10 to 15 years.

PAVIN: Developing a new antibiotic, or any other drug really, goes like this: Scientists have a hypothesis that something might work, but they haven’t nailed that down yet. So they go to the lab and test it out. If that goes well, they can test it on actual humans.

OUTTERSON: That process for us is usually four or five or six years. It might be 10 to 15 million U.S. dollars to move it from the earliest stage to the end of the phase-one human testing—sometimes more, sometimes less. And then if they’ve made it, and most will fail along the way, but if they’ve made it through all these scientific challenges, then they’re available for phase-two and phase-three larger human clinical trials, which are finally needed for FDA approval.

LOVE: Most drugs fail when they reach the FDA, actually. Estimates suggest that about 10 percent, maybe as much as 14 percent, of drugs that begin the process actually reach the finish line.

When it’s all said and done, the cost of developing an antibiotic can surpass $1 billion. And that’s not just for antibiotics. It’s the same for a lot of drugs.

It’s a staggering investment and a big risk. It’s why the government gives drugmakers a monopoly period on their product, so they can recoup their investment, and then some, before all the generics come in and inevitably lower prices.

STARC: And there’s a good reason we do that because otherwise nobody would invest in creating new drugs.

LOVE: To take this full circle, when the government can force drug manufacturers to lower prices for Medicare patients, it messes with a big incentive driving these drugmakers: the potential for a payday.

And when you start hacking away at that payday, suddenly that investment doesn’t look as enticing.

That’s the logic. We’ll pay less to get less in the future.

PAVIN: But will we really? It all feels kind of hypothetical, doesn’t it? We thought so. Like, how can we know that innovation will take a hit in a windfall-less world without having a crystal ball?

But then we stumbled across something that gave us a more clear view of stakes. And once again, that something is the market for antibiotics.

Let’s back up to tell you a little bit about how great it is that we, the humans, have antibiotics.

[music]

OUTTERSON: Think about what the world was like before penicillin.

PAVIN: Kevin Outterson again.

OUTTERSON: People actually died from a scratch in the garden as it became infected, and all sorts of death and disease occurred before we had the safety net of antibiotics.

PAVIN: Antibiotics are actually one of the most valuable drug classes in human history. Even today, bacterial infections are responsible for about 1 in every 8 deaths. And of course, antibiotics target bacteria behind these infections.

LOVE: But here’s the catch with antibiotics. They stop working over time, and that makes the market for antibiotics pretty unique.

OUTTERSON: If you invent a cancer drug or a pain drug, it’s going to work forever, literally forever. But we have to remember that every single antibiotic we have today will eventually become useless because of evolution. Resistance will destroy all of them.

LOVE: Bacteria are always wheeling and dealing, coming up with new ways to beat out our antibiotics. Which means we always need to be developing new ones.

And you’d think that would be a good thing—if you’re in the business of making antibiotics. But there’s another thing about this class of drugs that throws a wrench in that. We’re supposed to not use them. Well, not as much as we currently do. Basically, the less we take them, the longer it takes bacteria to find new ways around them.

And because we are supposed to be cautious about using them, especially the ones bacteria haven’t developed resistance to yet, that makes the business side of things real dicey for drugmakers.

OUTTERSON: The newest antibiotics actually are used very sparingly until the doctor is sure that they really need it. And we don’t have great diagnostics to tell the doctor very quickly when that is true. And so it’s almost like the antibiotic reaches the market, and it’s put behind glass like a fire extinguisher: “break glass in case of emergency.”

LOVE: What’s good for humans here—using these antibiotics sparingly—that’s bad for business.

PAVIN: Yep! But there are still companies out there investing in the development of new antibiotics, despite this lack of a payday on the horizon. And Jess, this all got me thinking that if they could succeed in this big pharmaceutical market, knowing that they pretty much can’t have a blockbuster drug on their hands, surely other drug companies can too. Maybe we don’t need to be paying so much for drugs here in America, you know?

LOVE: You went rogue on this adventure. So, talk to me: Did you find a drug company to chat with?

PAVIN: I did!

Ted SCHROEDER: Ted Schroeder, Chief Executive Officer of Nabriva Therapeutics.

PAVIN: This is Ted Schroeder. He heads up Nabriva. It came out with an antibiotic called Xenleta, which treats a certain type of pneumonia. Bacterial pneumonia.

SCHROEDER: As opposed to a pneumonia that develops in the hospital, this is a bacterial pneumonia that you would encounter in the community. It’s the most common form of pneumonia that’s bacterial.

PAVIN: As we all now know, coming up with new antibiotics and other drugs is a painstaking process. This one was no exception. But luckily for Nabriva, Xenleta got its FDA approval a few years ago, and it was off to the races.

So I was really excited to see if he had any tidbits of knowledge that he could impart on me about how Nabriva made the business of antibiotics work. So I asked him.

PAVIN: Well, how does Nabriva make it viable?

SCHROEDER: I’m sorry, say that again?

PAVIN: How does Nabriva make developing antibiotics viable if it is such a punishing area for drug companies to invest in?

SCHROEDER: Well, we haven’t, and in fact, we made the decision earlier this year to wind the company down. The enthusiasm among investors to continue to invest in anti-infective companies has been more muted than the general biotech sector. So we just couldn’t bridge from where we were this year to profitability next year.

PAVIN: Oh, no!

LOVE: Wait, his company is folding?

PAVIN: Yeah, at the time we spoke, that’s what he said.

Outterson, with CARB-X, said this is the reality for this market. It’s actually why CARB-X was created to begin with: it helps fund and support these kinds of endeavors, which are just not the kind of thing our market supports right now.

Outterson again.

OUTTERSON: There’s over a thousand cancer drugs in development, but about 40 antibiotics in development, which is a remarkably low number considering the human health burden of bacterial disease. Bacteria kill 8.8 million people around the world every year. If that was its own category, that’s more people than that die from HIV or malaria.

LOVE: Okay, so in a very extreme way, this is making Starc’s point. If the profits aren’t there, neither is the investment.

PAVIN: Yeah. I mean, to be clear, Starc and Garthwaite aren’t necessarily making a blanket statement that we should just douse drug companies with money and not ask any questions about it. What they are saying, though, is that it’s a trade-off.

STARC: If you do something with the goal of lowering drug prices, you’re going to get less innovation. Whether that’s good or bad kind of depends. So I don’t think we have a good sense of exactly the magnitude of that trade-off. It’s really, really hard to think about drugs that don’t come to market. But we can lay out that that’s the important bit.

PAVIN: There’s a choice we have to make as a country, Starc says. Go with the situation we’ve got now; promise a huge payday for developing groundbreaking drugs, but ones that only some Americans can afford.

Or we can make the choice that a lot of other countries have made, which is to prioritize affordability and access today. So maybe no groundbreaking drugs for rare cancers or Alzheimer’s tomorrow, but at least everyone will have equal access to what’s on the market right now.

This is a huge decision we have to make, and different people will come to different conclusions. Like, maybe you, dear listener, are thinking “hey, we’ve got a ton of great stuff on the market now, so let’s make it cheaper so everyone can afford it.” Which makes sense. But if you’re someone with Multiple Sclerosis or Alzheimer’s, where current treatments aren’t great, maybe you want to prioritize future treatments instead.

LOVE: But Laura, other countries do get access to new drug therapies! And for lower prices!

PAVIN: Well sure, but, according to Garthwaite, that’s because we pay so much. We’re a massive market that inspires a lot of innovation, and part of the reason the incentives are so good is because Medicare pays full price. And if we’re uncomfortable with that, the alternative really is less, and slower, innovation.

We have to decide what we can live with. But Americans aren’t having this conversation at all. Here’s Garthwaite.

GARTHWAITE: There are no secrets to low drug prices. There’s no secret to spending less on medication. You just have to be willing to say “no” to things today, and maybe “no” to things in the future. And we have high drug prices in the U.S. because we like people to get access to all the drugs. It puts us in a pretty bad negotiating position in terms of getting lower prices, but a good position in terms of providing the incentives to get more innovation in the future. And so it’s just sort of a trade-off.

[music]

* * *

LOVE: The system we have has pluses and minuses. A big plus is that it gives us new therapies and treatments that we would not otherwise have. In fact, it gives the whole world a lot of therapies and treatments that it would not otherwise have.

PAVIN: But, it still allows pharmaceutical companies to get away with things that a lot of us lay people would classify as shady.

Like, consider the cancer drug, Imbruvica. It’s expensive—costs Medicare billions of dollars annually. But then, a few years ago, scientists found that a lower dose of it might be effective for some patients. They could take less of the drug, and the payers would save some money, yay!

But then Imbruvica’s manufacturers tried to switch to a new dosage and pricing model that basically would have reversed those savings. They got a ton of blowback, so it didn’t stick, but it was still a bad look.

LOVE: There was also a lot of buzz about the pharmaceutical company Gilead. They had this HIV drug that worked well for a lot of people but led to really toxic side effects in some patients. The New York Times talked to a patient who said he ended up developing kidney disease and osteoporosis.

[clip from The Daily]

David SWISHER: I would say between 2006 and 2011, it had gotten progressively worse—just really achy, like achy inside my bones. And just really like someone had beat me up—just that achy all over.

Rebecca ROBBINS: And so after a long time trying to figure out what was going on, David’s primary care doctor had an idea. He suggested ordering a scan of David’s bones.

SWISHER: OK, so we did it. And so I sat there. And he came in, and he says, “well, it’s like bones of a 90-year-old woman. I’ve never seen anyone at your age have such severe osteoporosis.”

LOVE: That was the patient, David Swisher, talking to reporter Rebecca Robbins on The Times’ The Daily podcast.

And okay, this is sometimes just how it is. Side effects can be really tough. But the problem, allegedly, is that Gilead was working on a newer drug with fewer side effects.

The company was accused of delaying the development of the new HIV drug because their current HIV drug was still under patent protection. The implication was that they didn’t want to release a better version just yet because it would eat into the existing one’s profits.

PAVIN: Patent protection slowing down innovation? How’s that for a misaligned incentive?

I actually pushed Starc on this very thing—the Gilead of it all.

PAVIN: Yes, so we really have good and competitive markets in the drug market if companies like Gilead can withhold a better HIV treatment for when its initial patent expires?

STARC: So there’s a bunch of, for lack of a better term, “shenanigans” that exist because of the way that we reward firms for coming up with innovation and innovative drug therapies. And so I cannot imagine the reform to the patent system that avoids that. That seems like a natural consequence of the incentives that they face. And so I don’t know. I don’t know what the policy recommendation is.

* * *

PAVIN: So this is the double-edged sword we’re left with. But Starc and Garthwaite say, hold on a second. That doesn’t mean we can’t do anything at all to address the innovation and price trade-off. There is a way to get more bang for our buck, here in America.

The two of them, somewhat recently, put their heads together to offer some policy recommendations. And what they want to see, overall, is more competition and transparency up and down the drug value chain, which would help the market function a little better.

For example, they want to see the FDA ease up on its approval process for generic drugs. Right now, it takes too long, which means consumers are paying brand-name prices for longer than they have to. Speeding up that approval process would get those competing generics in there faster, which would lower prices faster.

LOVE: Another reform would take aim at the shadowy figures known as the pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs.

PBMs are how insurance plans get discounts on drugs that their patients take. The PBMs are their negotiators. But there’s a concern that maybe PBMs are skimming too much off the top of the rebates they negotiate, or maybe they’re conspiring to keep drug sticker prices high because they get a bigger rebate from that.

LOVE: In June, a New York Times investigation found instances where PBMs did, allegedly, do some sneaky things. They found that PBMs sometimes pushed patients toward drugs with higher out-of-pocket costs, or wildly overcharged insurance plans for generic drugs. One PBM, Optum Rx, allegedly set up an offshore subsidiary, which allowed them to retain billions of dollars in negotiated savings, without having to share them with the employers they were hired by.

What’s a bit unclear in all this discussion is who benefits from the decisions that PBMs make. We know that patients don’t always benefit, like when they have to pay higher out-of-pocket costs. But we also don’t really know how much employers benefit, either—and after all, they are the ones who hire PBMs to save them money. If employers aren’t benefiting, what good are PBMs doing?

LOVE: This is where Starc and Garthwaite say we need a little more information—more transparency into their contracts with drugmakers and insurance plans—because right now, they are confidential. Our professors say that sunlight would be the best disinfectant for this industry.

PAVIN: But to say that any of these measures will get to the endpoint that some lawmakers and consumers want to see—which is European-type prices paid at the pharmacy—that’s not what any of this will do.

Which is not satisfying. But that’s kind of the reality in the drug space. There isn’t any one silver bullet to lower drug prices in a massive way, not unless we want to make some big trade-offs. Like killing the incentive to come out with the next Earth-shattering drug that, who knows, might cure cancer?

GARTHWAITE: Now, where I and, I think, Amanda does as well, get annoyed with policymakers is when they try and assert like, “No, we can cut prices today and we’ll get the same amount of drugs in the future.” That’s just not going to happen. We might be willing to accept fewer drugs, but we have to actually have that conversation. Otherwise, we’ll make bad policy.

PAVIN: I have to say, if I were to ask myself this question of what system I wanted …

I’m really embarrassed to say that the current one works pretty well for me right now. I have good insurance. My extended family has good insurance. And dementia is something I worry about for us. My grandma had it. And if our current incentive structure fast-tracks potential new therapies for diseases like these, I can’t say that I dislike that.

But it’s also really hard to ignore that we do already have great drugs for conditions that people have right now. You might be one of those people. And if you can’t access them, or if you go broke accessing them, that’s a pretty bitter pill to swallow.

LOVE: Yeah, and so that’s the conversation someone needs to initiate. But, until we start having that chat, we do have Garthwaite and Starc’s policy recommendations! Which they fully recognize aren’t the sexiest but might be the most realistic way to get the market working better than it is now.

[music]

LOVE: Next week, on our final episode of this season of Insight Unpacked: Could we, the patients, be part of what ails our healthcare system?

GARTHWAITE: Does that shot need to happen within the confines of the megaprovider? There’s a choice there. But you could have gone to an independent allergist.

PAVIN: Wow! Now, I feel really bad for getting my allergy shots at this outpatient center.

LOVE: We turn the lens on ourselves.

PAVIN: But more than that, where should our healthcare system go from here? Is there some kind of recipe we can turn to?

We get into that next week.

[CREDITS]

PAVIN: While you’re waiting for our next episode, you can check out links, supplementary materials, and images for this episode at kell.gg/unpacked.

This episode of Insight Unpacked was written by Laura Pavin and edited by Jess Love. It was produced by the Kellogg Insight team, which also includes Fred Schmalz, Abraham Kim, Maja Kos, and Blake Goble. It was mixed by Andrew Meriwether. Special thanks to Craig Garthwaite, Amanda Starc, Kevin Outterson, and Ted Schroeder. As a reminder, you can find us on iTunes, Spotify, or our website. If you like this show, please leave us a review or rating. That helps new listeners find us.