Some time ago, he was visiting the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and noticed something interesting. “The paintings narrowed in style and subject after Van Gogh’s move to the South of France in the late 1800s,” says Wang, a professor of management and organizations at Kellogg. That shift, it turned out, signaled the start of the artist’s most successful period, including iconic pieces like Starry Night Over the Rhone and Van Gogh’s Chair.

The observation gave Wang a much-needed clue to a research question he’d pondered for years: What triggers a hot streak?

“Hot streaks,” or career-defining periods of unusual success, have been observed in most every creative domain, from Einstein’s “Miracle Year” of groundbreaking discoveries, including the Theory of Relativity, to director Peter Jackson’s box-office-smash Lord of the Rings trilogy. Wang’s previous research suggested that hot streaks appear at random during a career, like a comet with no predictable timing.

“Hot streaks seem to happen for most everyone,” Wang says. “But it seemed like they come about by ‘magic’ or just randomly.” That is, no one had found a reliable precedent to these high-success periods.

Until now.

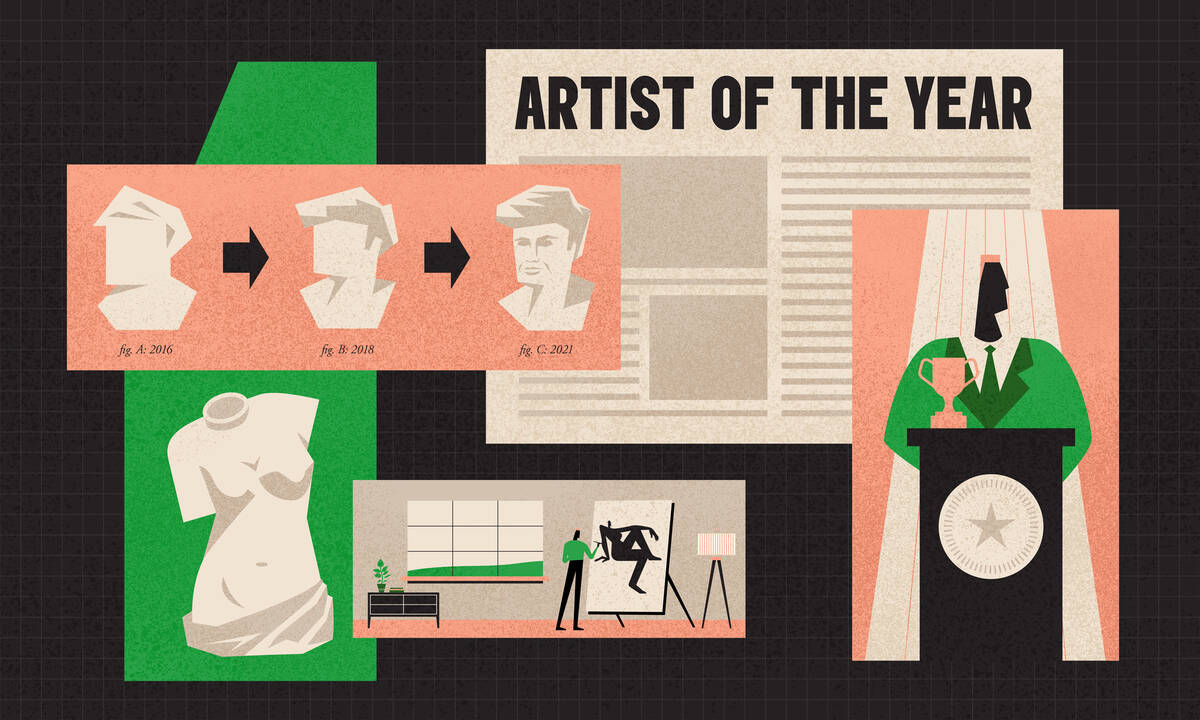

Inspired by that trip to the Van Gogh Museum, Wang and his colleagues designed a study that used AI to analyze millions of works by artists, film directors, and scientists, in search of potential hot-streak-triggering mechanisms.

They found that, across domains, hot streaks are typically preceded by a specific combination of exploration—more diverse work across styles and focus areas—followed by exploitation—a narrower focus on a particular category of work that drives outsized success.

“We’ve found one of the first identifiable regularities related to the onset of a hot streak,” says coauthor Jillian Chown, a Kellogg associate professor of management and organizations. “It can help individuals and organizations understand the types of activities to engage in, and the optimal sequence to use for bigger impact.”

AI-Driven Analysis

Before this study, the biggest impediment to understanding what triggers a hot streak was not knowing how to characterize creative works in a standard way, across people’s careers. What constitutes an artist’s style, for example? How would one categorize a filmmaker’s diverse productions?

To address that problem, Wang and Chown, along with lead author Lu Liu, a PhD student at Kellogg’s Center for Science of Science and Innovation, Nima Dehmamy, a research assistant professor at Kellogg, and C. Lee Giles at the Pennsylvania State University, developed a deep neural network for the three domains of focus: paintings, film, and science. For example, the AI systems used visual-recognition technology to analyze the types of subjects and brushstrokes in paintings, and identified film genre and style by analyzing plot summaries, cast, and other information available online. They used this innovative method to examine the careers of 2,128 artists, 4,337 directors, and 20,040 scientists—millions of works in total.

“It has to be the combination of exploration followed by exploitation: experimenting in different areas, learning different domains and approaches, then really hunkering down and developing that body of high-impact work.”

— Jillian Chown

The neural network enabled the researchers to capture each person’s style, areas of focus, and other dimensions related to their career output, to understand how their body of work evolved over time, in the context of exploration and exploitation.

To understand success and impact—the basis for a hot streak—the study used measures that are generally agreed upon to show success in each field: number of citations of scientific works, art-auction prices, and IMDB film ratings.

“Our approach allowed us to correlate hot streaks with each individual’s creative trajectory, to understand what might predict these streaks,” Wang says.

A Recipe for Success

The results make clear the “recipe” for a hot streak: exploration of creative options followed by exploitation of a specific “lane” of work ultimately leading to greater success. This held true across all three domains studied.

For example, director Peter Jackson made films that fell into horror, comedy, drama, and other genres (reflecting a period of exploration) before hitting it much bigger with the Lord of the Rings fantasy franchise. Analysis of painter Jackson Pollock’s work, similarly, showed exploration of a wide range of styles before the focused “drip period” (1946–1950) that elevated him to global fame.

The research found, further, that exploration or exploitation by itself is not enough for a hot streak. That is, only the specific exploration-exploitation sequence led to the highest increase in likelihood of a hot streak: hot streaks following that sequence were 20.5 percent, 13.8 percent, and 19.2 percent more likely for artists, directors, and scientists, respectively, versus after a random point in a given career. Exploration and exploitation alone were associated with no such increase.

“If you just do one or the other, you don’t get the full impact,” Chown says. “It has to be the combination of exploration followed by exploitation: experimenting in different areas, learning different domains and approaches, then really hunkering down and developing that body of high-impact work.”

Wang agrees: “Our work shows that people experiment and likely gain new skills from work in different subfields, and then help find the best one to exploit, which seem crucial for hot streak.”

In line with this, the study found that the hot-streak area of exploitation usually isn’t the most recent one explored, supporting the idea that people are gathering information and experience across a number of areas then moving forward with the best-fitting one.

Promoting and Supporting Hot Streaks

The research has implications for how individuals and organizations can spur their own hot streaks.

Individuals pursuing any creative endeavor now know that the exploration-exploitation sequence is most likely to lead to a hot streak. “This combination of creative activities is particularly potent,” Wang says. In practice, this might mean exploring multiple subfields to find the right fit—such as a scientist pursuing research in multiple biology domains before settling on one of greater focus.

Organizations can also make use of hot-streak insights. Academic institutions and grantors, for instance, can analyze professors’ and researchers’ career paths carefully to see who’s more likely to hit a near-term hot streak, and support that individual through advancement, funding, or other resources.

Businesses, similarly, can apply this understanding of hot-streak dynamics to decide how they manage intellectual property.

“A firm could look at how concentrated their patents are in certain areas to understand their pattern of exploration and exploitation related to innovation” Chown says, and then make adjustments to work toward a hot streak. Similarly, a pharmaceutical or biotech business could examine how it works within and across products for different therapeutic areas—cancer, diabetes, etc.—as it seeks to explore and exploit.

The research may also have implications for how organizations should structure exploration and exploitation, and how they should incorporate these steps into business strategy.

Some firms have different groups working on exploration and exploitation, for example, separating out a research and development team from product teams. “That runs the risk of not letting individuals have their own exploration and exploitation sequence,” Chown says, because a given team member would work only on exploration or exploitation, rather than both.

The researchers point out there’s much more to know about what triggers a hot streak. “It would be valuable to know what people’s motivations for exploring certain things were,” Chown says.

Similarly, it’s not yet known why an individual makes the move from exploration to exploitation. For example, “it’s still not clear how much exploration is the ‘right’ amount before moving into exploitation,” Wang says.

But even with so much left to know, Wang says, “we now finally know hot streaks don’t just happen by magic. It’s about a person exploring different areas, then finding the right space to exploit for greater success.”

Featured Faculty

Previously a Visiting Predoctoral Fellow at Kellogg

Associate Professor of Management & Organizations

Professor of Management and Organizations; Professor of Industrial Engineering and Management Sciences (courtesy); Director, Center for Science of Science and Innovation (CSSI); Co-Director, Ryan Institute on Complexity; Director, Northwestern Innovation Institute

About the Writer

Sachin Waikar is a freelance writer based in Evanston, Illinois.

About the Research

Liu, Lu, Nima Dehmamy, Jillian Chown, C. Lee Giles, and Dashun Wang. 2021. “Understanding the Onset of Hot Streaks across Artistic, Cultural, and Scientific Careers.” Nature Communications.

Read the original