Featured Faculty

Thomas G. Ayers Chair in Energy Resource Management; Professor of Management and Organizations

In a 2010 survey of CEOs of global corporations including HSBC, Novartis, PepsiCo, and Timberland, over 93 percent of respondents said that sustainability issues—as related to the environment and other areas—were crucial to the success of their business.

Companies across sectors are actively pursuing sustainability, from developing eco-friendly products to promoting job training for low-income populations, in search of operational and reputational value. As such, setting an effective sustainability agenda is paramount. But sustainability is such a broad mandate that no company can pursue all possible aspects, and most firms lack divisions or business units dedicated to sustainability efforts. One important question, then, is why some sustainability issues receive more organizational resources than others. Moreover, what factors will promote or impede success in executing on a given issue?

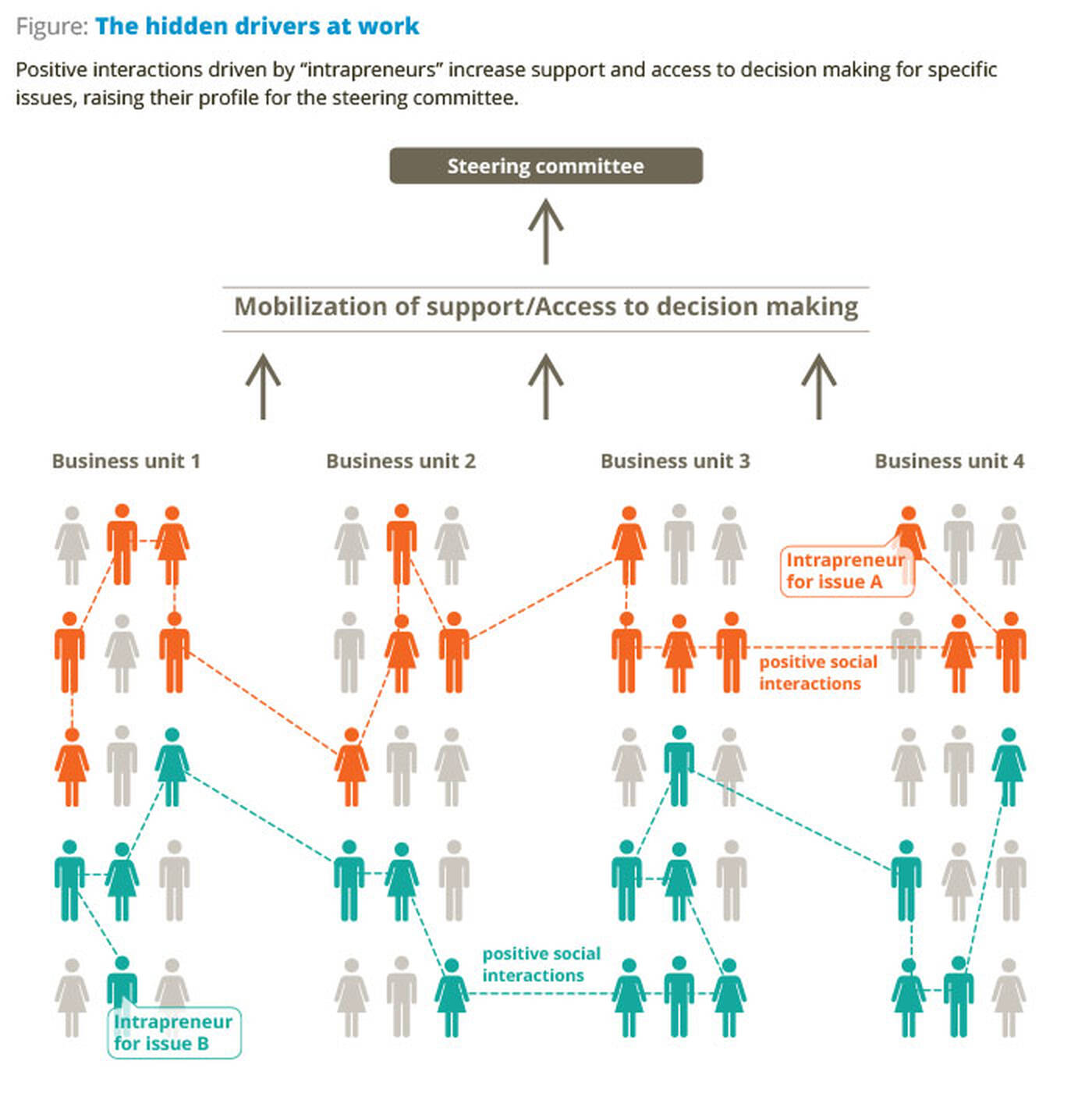

Recent primary research I conducted with Sara Soderstrom suggests that the answers to these questions go well beyond top executives’ decisions, to organization-wide efforts to build support and create momentum around specific sustainability issues. As in social movements outside organizations, issue entrepreneurs raise the profile of specific issues, mobilize colleagues to dedicate resources to these, and form coalitions. In a corporate setting, understanding how these “intrapreneurs” (an innovation-research term for individuals who use entrepreneurial tactics to drive change) promote specific issues through small-scale interactions can help managers understand how agendas within and outside sustainability are formed and executed, along with routes to improving the impact of agendas.

Sustainability at Alpha, Inc.

To understand the drivers of corporate sustainability agendas we collected data over 18 months from formal and informal interviews, meetings, and internal documents at “Alpha, Inc.,” a US-based global medical device firm. In 2007 Alpha sought a more strategic approach to sustainability and launched an executive-level steering committee to set and act on priority areas. Eight streams of sustainability-related issues were considered, from greening the supply chain to community development. Funding did not influence a given issue’s attractiveness, as none of the issues had prior or planned funding, and all were associated with positive business cases.

Over the next two years, only a subset of the issues gained and maintained internal resources (i.e.,such as time, manpower, funding), becoming part of Alpha’s sustainability agenda. For example, the issue of greening the supply chain—through a multi-pronged effort to decrease Alpha’s environmental footprint—rose to become a formal priority for the steering committee, with incorporation of sustainability into all supplier contracts and requests for proposal. Similarly, an initiative to develop business-model innovations for bottom-of-the-pyramid communities gained momentum after a year of limited activity, gaining a dedicated cross-divisional working group and an approved budget. In contrast, the issues of developing green products and profitably providing waste streams to partner corporations never caught on, despite initial interest and momentum.

Sustainability and other corporate agendas are core components of ongoing business success.

While executives can influence agendas, they cannot determine their evolution. The trajectories and outcomes of agenda issues under consideration depend largely on issue intrapreneurs and their everyday workplace interactions. These are the hidden drivers of sustainability agendas, and they typically work from the bottom of the organization up.

The Hidden Drivers at Work

Successful small-scale interactions—from hallway conversations to structured meetings—motivate participants to align their interest and attention around similar issues and devote energy to these issues. Unsuccessful interactions divide attention and diminish energy. Both types of interactions beget similar future interactions. At Alpha, a successful interaction around the bottom-of-the-pyramid sustainability issue took place at a cross-business-unit workshop: three intrapreneurs used subtle shifts in focus to help more skeptical participants understand the initiative’s low capital investment requirement, emotional appeal, and likely support from top management. The workshop stimulated synchronicity around the issue, yielding shared focus and enthusiasm. A meeting over a proposed new-product-materials database provided a counter-example. Here, the would-be intrapreneur and other participants failed to align their foci of attention and emotional tone, leaving all parties feeling disconnected.

Klaus Weber discusses how social interactions drive sustainability initiatives View all CSR videos on YouTube

We found that repeated successful interactions boost sustainability issues through three interrelated mechanisms:

Harnessing Hidden Drivers for Sustainability and Beyond

Issue intrapreneurs need not focus on sustainability alone. The hidden drivers featured here may be used to promote issues in any areas that have not been formalized in organizational systems and hierarchies—technological innovation and growth initiatives, for example. Across areas, a systematic intrapreneurial (versus a top-down) approach promises to tap more effectively into employees’ passion and knowledge. Following several guidelines at the intrapreneur and organizational level can help drive more successful issue-related interactions.

At the intrapreneur level:

At the organizational level:

Sustainability and other corporate agendas are core components of ongoing business success. Understanding and influencing the pattern of everyday interactions, or hidden drivers, of agenda issues will help individuals at all organizational levels mobilize support for initiatives that can yield value for their company and community.

Soderstrom, Sara B. and Klaus Weber. 2011. “Corporate Sustainability Agendas from the Bottom Up.” European Business Review (March/April): 6–9.