Auctions are everywhere. And while they’ve been around for thousands of years, advancements in auction theory—the study of how people should strategize in different auction formats—have provided frameworks to solve some of the world’s most complicated problems.

The importance of auctions was highlighted recently with the awarding of the Nobel in economics to two auction-theory scholars, Paul Milgrom and Robert Wilson, both at Stanford University.

Milgrom was a faculty member at Kellogg in the department of managerial economics and decision sciences (MEDS) from 1979–1983, where he produced some of his seminal work on auction theory in collaboration with Robert Weber, a professor emeritus at Kellogg.

Paul Milgrom is the third scholar to receive the Nobel Prize for work originating at Kellogg. In 2016, Bengt Holmström was awarded the prize for his contributions to contract theory, while Roger Myerson received the prize in 2007 for his work in mechanism design and auction theory. Milgrom, Holmström, and Myerson were all MEDS department colleagues in the late 70s and early 80s, a period when their respective fields were little studied elsewhere.

In light of the recent prize, a number of current Kellogg faculty reflected on the school’s unique intellectual history in auction theory and the field’s widespread impact.

Moving Theory Forward at Kellogg

While they were together at Kellogg, Weber and Milgrom were drawn to collaborate by their common interest in auctions.

“We turned our attention to what was a major open question in auction theory at that time,” Weber says. If bidders in an auction are uncertain about the value of the item being sold, how will that impact revenue for the seller?

In tackling this question, Weber and Milgrom built upon the foundation that preceded them, focusing on a few key aspects of auction theory: common- and private-value auctions, and the “winner’s curse.”

Kellogg’s Jeroen Swinkels explains these concepts. “A common-value auction,” he says, “is one where you and I have the same basic preferences over what we’re buying, but we might have different beliefs” about the item’s actual valuation because we are each relying on our own private information. This means that knowing how much someone else values the item can inform our own valuation. Think of an auction for drilling rights for a tract of land: all the bidders might have different estimates of how much oil lies underneath, but they share the “common value” of making as much money as possible.

In private-value auctions, however, the bidders understand that they do not all derive the same value from the item, making their valuations independent from other bidders’.

The “winner’s curse,” Swinkels explains, “is the idea that as soon as I win, I should be nervous because a bunch of smart people around me bid less than I did and so maybe that means it’s not as good as I thought it was.” Bidders who understand the winners’ curse should then bid cautiously to avoid overpaying for the item. There is evidence that this actually happens in bidding for drilling rights.

Milgrom and Weber’s research moved this foundational theory forward by providing a framework where auctions could have elements of both private- and common-value auctions. The key result of their research—the “Linkage Principle”—determined that if an auction provides more information to bidders, then the winner’s curse is mitigated since bidders are not as worried that they made a bad decision. This means they will bid more aggressively and the auction’s revenue is higher on average.

“The Linkage Principle implies that the seller can raise revenues by committing to a policy of openly and honestly revealing any information held by the seller of relevance to the quality of the item being sold,” Weber says.

The auction form itself can act as a channel to provide information to bidders. In “Dutch” auctions—so called because they are used to sell tranches of flowers in Holland—an auctioneer lowers the price until someone buys. In the more familiar “English” auctions, an auctioneer raises the price until the highest bidder left buys the item.

More information is revealed in the course of an English auction as bidders learn about each other’s valuation from the bids they observe. Milgrom and Weber’s research then shows that the English auction must generate more revenue for the seller than a Dutch auction since it reduces the winner’s curse. Thus, their research has implications for practical auction design.

Interestingly, these insights for the common-value scenario act as a counterpoint to one of Roger Myerson’s surprising insights for the private-value case. He showed that, under certain circumstances, many auctions, including the Dutch and English ones, give exactly the same revenue to the seller. Then, other considerations, such as simplicity, might determine which auction the seller might choose, given that revenue is moot.

This back-and-forth between Myerson, Milgrom, and Weber was one instance of “the intellectual zeitgeist of game theory research that was going on in the MEDS Department at that time,” says Kellogg’s Sandeep Baliga. “The research of these three and many others who were at MEDS is now part on the canon of economics. It continues to inspire research to this day.”

Real-World Applications

This research went well beyond abstract theory. For instance, in the early 1990s, the U.S. government discovered that Salomon Brothers was bidding illegally on Treasury securities in order to corner the market. When the government asked Weber to help implement changes in Treasury auction procedures, he applied the research he and Milgrom had developed, advocating for a market design that was less susceptible to manipulation and at the same time could be expected to lower the cost of financing the national debt.

Advancements in auction theory have also had a significant impact on telecommunications, specifically in the auction format used by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) when it first decided to sell radio spectrum to telecommunications companies rather than freely give it away, as it had done in the past.

A major contributor to the underlying theory that informed the design of these auction formats was Kellogg’s Mark Satterthwaite, professor emeritus in MEDS.

“Mark founded the literature on large auctions,” Swinkels says. This is when, unlike a simple auction where there is just one item for sale, there are both multiple items for sale and multiple bidders.

“Think about an auction for shares of a farm or emissions rights in a trading market. In those auctions, there’s lots of buyers and sellers—a double auction—with bidders on both sides. These auctions are performing two fundamental roles: they’re trying to put together what different traders know, and they’re trying to perform an allocation role, where they’re wanting to make sure the right people are getting the right objects.”

Milgrom and Wilson took the work on large auctions and developed combinatorial auctions (where, unlike in the “double auctions,” the multiple objects being auctioned differ from one another)—work for which they won the Nobel. In these auctions, bidders care about getting combinations of packages. For example, in the FCC radio-spectrum auctions, bidders cared not just about a single spectrum, but also about being the successful bidder on a geographically adjacent spectrum.

Kellogg’s James Schummer explains: “For example, Verizon or AT&T want to buy the rights to broadcast over the airwaves. If they want to broadcast signals all the way from New York to Chicago, they’re going to have to tie together the rights over certain geographical areas, and the FCC auctions off these rights simultaneously.”

Milgrom and Wilson’s auction design for the FCC has had a long-lasting impact. “I’m on my phone using data all the time,” says Kellogg’s Joshua Mollner. “A lot of the spectrum that cell-phone providers use to deliver that data is spectrum that they bought in auctions that were designed—indirectly or directly—by Paul Milgrom and Bob Wilson.”

The Right Solution for Complex Problems

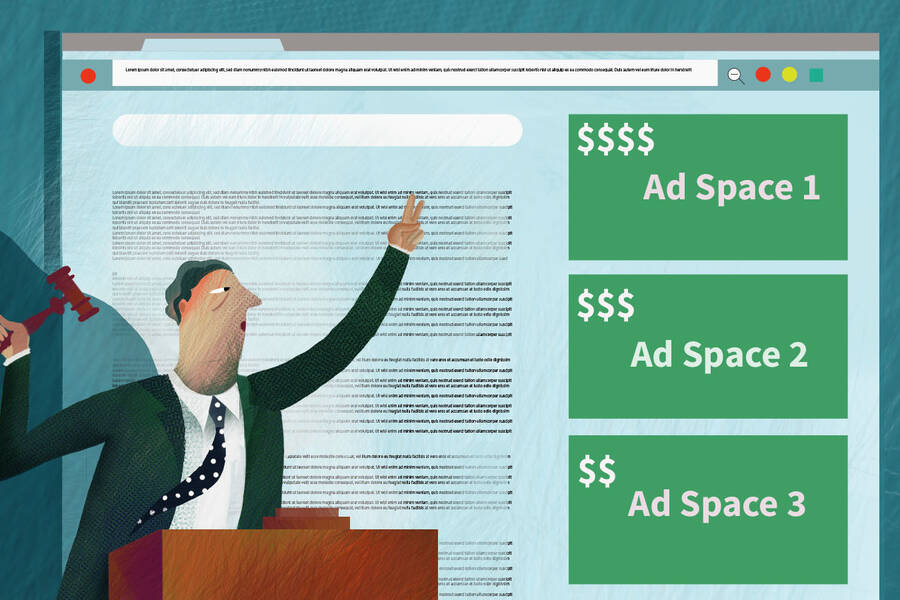

Due in large part to these innovations in auction theory, auctions are now used routinely to solve complex problems, “from running electricity markets—with minute-to-minute auctions—to government procurement,” Swinkels says. “They’re also used every time you put a search term into Google, where an automated auction is taking place in the background over which ads will be prominent. And one of the most profound applications of auctions is to create more-efficient frameworks for pollution control, especially as relates to global warming.”

Another example: American football. Baliga designed a Dutch auction for selling football tickets at Northwestern University.

“The idea is that you start off with a really high price, and lower it and lower it and lower it until the market clears,” Baliga says. “But you have to make sure people are going to buy at the high price because they know that the price is going to go down. So, you assure them. You say, “If the price goes down, you get a refund.” Roger Myeron’s work suggests that this kind of auction might be revenue equivalent to an English auction. But it is faster—you get your tickets straight away—and allows data mining behind the scenes to determine what price to set. This way of selling tickets proved to be very profitable for the auction.

Amazon uses a similar format if you buy a book before it’s been published. Amazon guarantees that if the price of the book goes down between the time that you purchase it and publication day, you’ll get a refund. This alleviates buyers’ concerns and is an effective system for Amazon to estimate demand for its products.

Advancements Continue

Researchers continue to advance auction theory, introducing new tools and frameworks for addressing current market problems.

For example, Mollner recently teamed up with Milgrom, who was his PhD advisor, on a new paper that looks at the type of auction used by search engines to sell ads. They looked specifically at the concept of “trembles,” or moments when a bidder behaves differently than expected, as if their hand trembled.

You can make better predictions about the bids you will see in an auction if you can predict which of the potential trembles will be most likely. Previous literature addressed how a particular bidder would most likely tremble but did not address which bidder would most likely tremble.

“That’s where Paul and I have come in,” Mollner says. “Our research allows you to make sharper predictions.”