Featured Faculty

Member of the Department of Managerial Economics & Decision Sciences faculty until 2018

Yevgenia Nayberg

Companies know they can lure and retain top talent by offering hefty bonuses, corner offices, or stock options. But what about workers at the other end of the spectrum who are a drag on company performance? How much attention should companies be giving to these problem employees?

A lot, according to new research by Dylan Minor of the Kellogg School.

Minor and his coauthor look at “toxic workers,” those who engage in illegal or unethical behaviors that might harm an organization. Toxic workers, the researchers find, complete lower-quality work, spread unethical behavior to other employees, and diminish customer satisfaction. In fact, the cost associated with employing a toxic employee is greater than the benefit of employing a top performer. It may be better for the bottom line, in other words, for organizations to put resources toward dealing with their toxic workers than to focus their energies on superstars.

“There’s lots of work on high performers, the superstars … but we need to understand the other end of the spectrum.”

The research also identifies predictors of toxic behavior and proposes strategies companies can use so they are not saddled with these problematic employees.

Minor, an assistant professor of managerial economics and decision sciences, has had a longstanding interest in the factors that go into designing an effective organization. He and coauthor Michael Housman, an executive with the talent management software firm Cornerstone OnDemand, decided to investigate the ramifications of toxic employees—a research topic that has rarely been studied.

“There’s lots of work on high performers, the superstars,” Minor says, “but we need to understand the other end of the spectrum.”

The researchers used a data set from Cornerstone, a consulting firm that provides companies with tests to assess job candidates and employees. The data included how employees self-assessed their skills, how good their skills actually were when tested on them, as well as how they performed if they were hired and whether they were fired. The data covered more than 58,000 hourly service workers at 11 well-known firms across several years.

Learn more about energizing people for performance at the Kellogg Executive Education program.

“The trove of data allowed us to follow workers over time and observe the predictors and consequences of toxicity,” Minor says.

How common is toxic behavior, which the researchers defined as “an egregious violation of company policy” that resulted in getting fired? In the researchers’ sample, a given employee had about a 5 percent chance of engaging in toxic behavior—like sexual harassment or fraud—during the period observed.

Toxic workers can have serious consequences for companies—often appearing to be great workers while actually undermining a company’s reputation.

The research finds that toxic employees completed their work more quickly than other employees. This may explain why an investment firm, for example, might not notice that a seemingly successful rogue trader is actually engaging in questionable behavior. But ultimately, toxic workers tend to deliver lower-quality work, as measured by customer satisfaction.

“In the short term, it looks like they’re doing well,” Minor says, “but the poor quality of their work can damage the firm’s reputation.”

Additionally, a higher density of unethical employees in a particular work group increases the likelihood other group members will display unethical behavior. In fact, when a person was in a work group with a high density of toxic employees, Minor saw a 47 percent increase in the likelihood that person would become toxic.

“It’s a damaging form of ‘ethical spillover,’” Minor says. “We can think of the behavior as a sort of virus, making the ‘toxic worker’ an apt label.”

Just how expensive are toxic employees? To quantify the harm they inflict, the researchers compared the value of hiring a superstar employee with merely eliminating a toxic one, based on performance data.

The results were startling. A top 1 percent superstar—a very rare high performer—brings an extra $5,300 in value by doing more work than an average employee does. Replacing a toxic worker with an average one creates an estimated $12,800 in cost savings over the same period by reducing the cost of turnover around that toxic worker. Similarly, replacing a toxic worker yielded almost four times the value of hiring a top 10 percent performer.

“That doesn’t even take into account the spillover, legal, and reputational effects of toxic workers,” Minor says. “So I think it is a conservative estimate.”

The researchers’ work uncovered several predictors of toxic behavior.

One had to do with confidence. Employees in the sample self-assessed their technical skills in several areas. Their assessment was then compared with subsequent measures of their actual abilities, yielding an over/under-confidence measure. Overconfidence was a strong predictor of toxic behavior.

“From an economic perspective, overconfidence often means getting your probability estimates wrong,” Minor says, “including underestimating the likelihood you’ll get caught for something unethical.” Workers who were overly confident about their spreadsheet skills, for example, might also have overestimated their ability to get away with tardiness or cheating on timesheets.

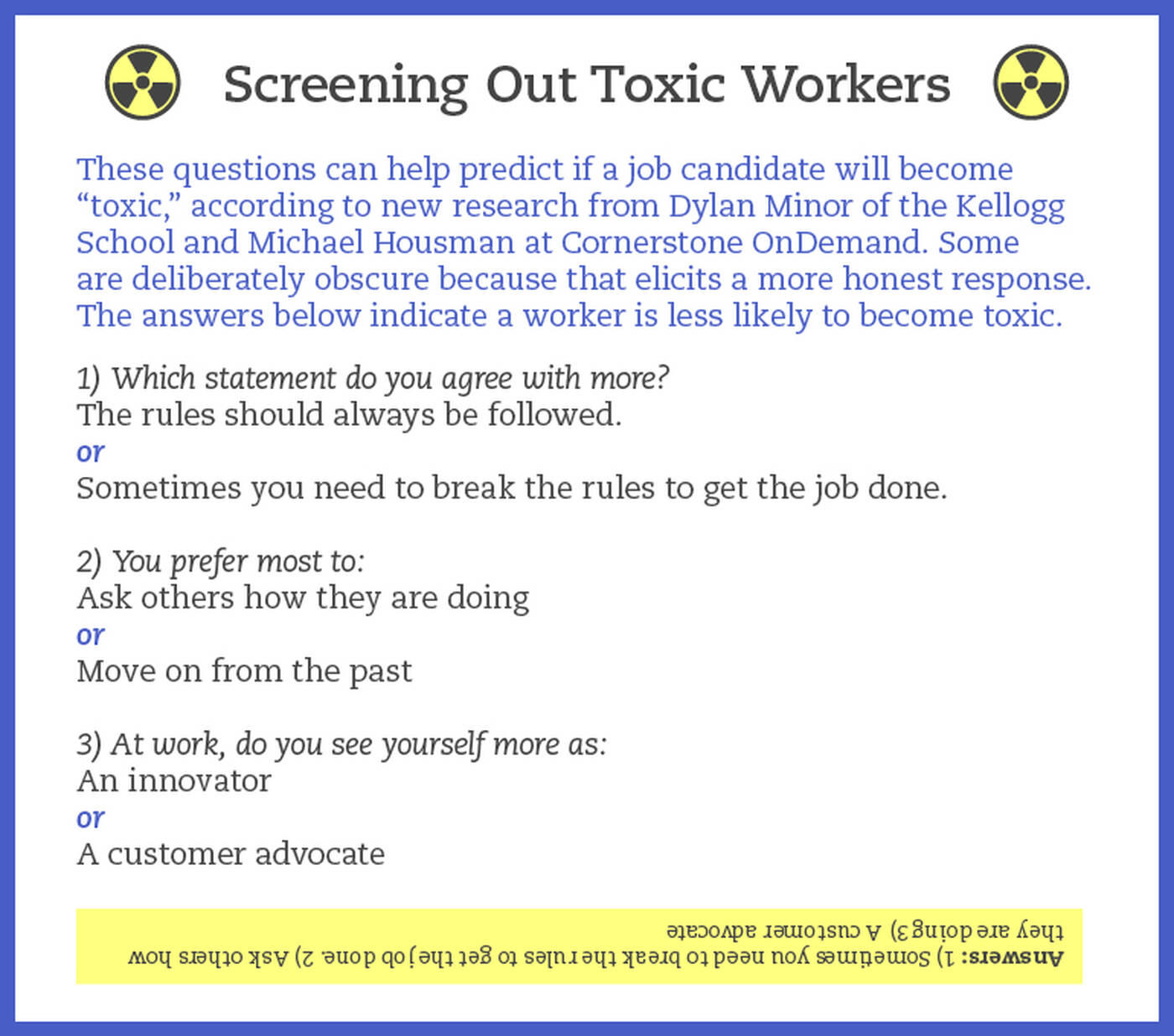

Several questions in the job-screening questionnaire evaluated how “other-regarding” the candidates were, meaning how willing they were to address other people’s concerns. Not surprisingly, the more other-regarding the candidates, the less likely they were to become toxic.

Another predictor was more surprising: employees who agreed with prescreen statements like “I believe that rules are made to be followed” were more likely to engage in toxic actions. “We can think of this as a clever honesty test,” Minor says. “Most people understand that there are times when it may not make sense to follow the rules.” So people who rigidly endorsed rule-following were, perhaps ironically, more likely to break them.

Finally, poor job fit—when employees were in positions that did not complement their talents well—was another predictor of toxic behavior.

So how do companies free themselves of toxic employees?

Avoidance has been the main tool to date. Most businesses try to screen out such candidates at the hiring stage. Minor advocates more strategic intervention. “Toxicity probably emerges from a combination of nature and nurture,” he says. “So while there may be a predisposition to these behaviors, we need to provide the right kind of nurturance to prevent them—just like putting all criminals in prison will certainly reduce crime, but reform can be a better approach for some of them.”

Minor is working on follow-up research by looking at more detailed data from one of the companies that was part of the large data set. He is interested in looking at people who are toxic to those around them but whose behavior may not be so extreme that it is actually illegal. What impact do those people have on their coworkers and company?

He’s also interested in the physical layout of a workspace as it relates to toxic workers, and is looking at that in his new research.

“Toxic workers tend to spread their effect across a whole floor of workers as opposed to really high-productivity workers, who only tend to have a positive impact within a close distance of those they work with,” he says. “Should you put [a toxic worker] at the corner of a workspace, in the middle? Should you put them next to a supervisor? Where should the high performer be? What’s an ideal way to configure this to maximize the value of a superstar and de-emphasize the spillover of a toxic worker?”

Housman, Michael, and Dylan Minor. 2014. “Toxic Workers.” Working Paper.