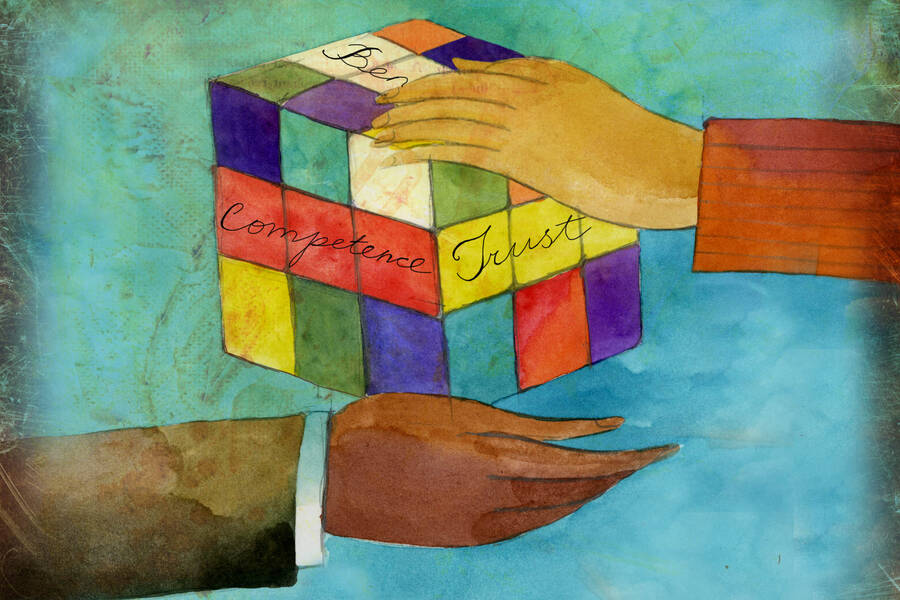

So how do you build trust in the workplace? Kellogg faculty offer advice for what individuals and companies can do to establish their trustworthiness.

As Harry Kraemer sees it, trustworthiness is a required trait for leaders. So Kraemer, the former CEO of Baxter International and now a clinical professor of leadership at Kellogg, has thought a lot about what leaders can do to be seen as trustworthy.

In the video below, which is part of The Trust Project at Northwestern, he lays out four ways leaders can establish trust.

One tip: make sure you take the time to understand all sides of a story or issue.

Leaders, he says, “establish trust because they demonstrate they really care about what each person has to say.”

Another important step in building trust in the workplace is ensuring that your company aligns its statements with its actions, according to Karen Cates, an adjunct professor of executive education.

For example, if a company says it welcomes new ideas, then its leaders need to be genuinely open to listening to them, Cates says. Even seemingly minor details are important. For instance, imagine a company that claims its greatest asset is its people yet fails to mention employees anywhere on its website.

“Alignment is critical because it lays the foundation for trust,” Cates says, “and trust leads to greater commitment. If you don’t have alignment, it doesn’t matter how great your benefits are. You still won’t have commitment from your employees.”

And, as research by Kellogg School professor Paola Sapienza finds, there are economic benefits as well: when companies are perceived by their own employees to have cultures of integrity, they show higher profits.

Sometimes organizations build trust in a counterintuitive way: by picking the wrong person for a job.That’s the conclusion of research from Daniel Barron and Michael Powell, both associate professors of strategy. The idea being that if you have promised to reward excellent work, you need to follow through, even if the person you’re promoting is not the best one for that new job.

But doing this can often be tricky. For example, the costs of assigning the wrong person to a job can be too high. And there are rarely enough rewards to go around. So how do companies navigate this without demotivating employees who feel that the company isn’t following through on its promises?

The researchers’ game theory model suggests that rewarding past excellence is most beneficial when an employee has truly excelled previously, while competing parties have not, and when the costs of favoring the party that has previously excelled are relatively low.

So while it may not be feasible all the time, the research shows that there are some situations where the benefits of rewarding past performance are so strong that they can overcome the benefits of actually giving the job to the right person. “That is where you promote the wrong guy,” Barron says.

Of course, another way to build trust at work is to eliminate opportunities for people to cheat.

There are plenty of ways to do this, of course, but here’s a simple way to get started: understand when people are most likely to engage in dishonest behavior, and arrange assignments accordingly.

According to research from the late J. Keith Murnighan, a professor of management and organizations, people are more likely to cheat when they are near the end of a job or a task. Under these circumstances, the dishonest behavior is motivated by something called “anticipatory regret”—an urge to avoid future feelings of regret at passing up a last opportunity for personal gain.

Murnighan and coauthors demonstrated this in a series of experiments. For example, hundreds of online participants were asked to flip a coin and self-report which side it landed on—with the possibility of winning a small cash reward for landing on one side versus the other.

The researchers analyzed the results of over 25,000 coin flips and showed that participants were more than three times as likely to cheat when they thought they would have no more opportunities to do so. By manipulating the timing of opportunities to cheat, the researchers showed that anticipatory regret was the likely explanation.

The findings have big implications for managing risk among short-term employees, Murnighan said.

“We tend to want to squeeze the last drop of productivity we can, particularly from part-time workers who aren’t coming back,” he said.

Instead, he recommended loosening contractor commitments near the end of an engagement to mitigate potential dishonesty.

“If you’ve got a two-week job, consider letting people go home at one o’clock on the last day instead of keeping them until 5 p.m.,” he explained. “When you give them a little bonus like that, they’re less likely to try and take some other kind of bonus for themselves on the way out.”

In general, cultivating trust is a good thing. But, under some circumstances, that trust can backfire. “There’s a dark side to it,” explains associate professor of marketing Kent Grayson.

In the video below, which is also part of The Trust Project, he explains the circumstances when trust may lead to worse outcomes for your business.